Behind the Gender-free Utopia of 'Every Bird a Prince' with Jenn Reese

The author speaks with SLJ about challenging gender roles, empowering young readers on the ace spectrum, and combating self-doubt.

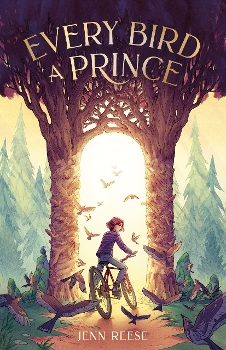

In their stunning contemporary fantasy Every Bird a Prince, Jenn Reese crafts a tale of seventh grader Eren, who must claim her truth in order to save magical birds, and her loved ones, from ancient evils that lurk both within the woods and within themselves. The author speaks with SLJ about challenging gender roles, empowering young readers on the ace spectrum, and combating those everlasting whispers of self-doubt.

Gender identity and questioning are central themes of your book, including magical birds who are referred to as they/them. What are you hoping to show readers about pronouns and gender?

This question makes me laugh a little, because modern middle grade readers often have a much greater facility with pronouns and gender spectrums than us older folks. I never assume I’m showing them or teaching them anything on those fronts. That said, I personally dislike the strict gender binary that permeates most of society. It made me happy to create a magical forest kingdom that had somehow escaped the idea of gender entirely. That’s not everyone’s vision of a utopia, but it’s mine. And I hope some readers will find this idea of freedom from gender expectations and biases refreshing, too.

This question makes me laugh a little, because modern middle grade readers often have a much greater facility with pronouns and gender spectrums than us older folks. I never assume I’m showing them or teaching them anything on those fronts. That said, I personally dislike the strict gender binary that permeates most of society. It made me happy to create a magical forest kingdom that had somehow escaped the idea of gender entirely. That’s not everyone’s vision of a utopia, but it’s mine. And I hope some readers will find this idea of freedom from gender expectations and biases refreshing, too.

Where did you get inspiration for this concept of Eren’s regular seventh grade life turning fantastical?

With this book, I knew I wanted to talk about the less obvious kinds of societal pressure we all face. Most of us can recognize bullies and understand that they’re trying to hurt us. But often the most insidious doubts and pressures come from our parents, our friends, ourselves, and even society in general. Those are harder to spot, and harder to fight—especially when they come from people who genuinely love us.

So in Every Bird a Prince, I made these forces easier to see (and more fun to write) by embodying them in the “vile frostfangs,” wolflike creatures whose cruel whispers echo directly in the characters’ heads and sap their strength and will. To resist them, Eren and Alex must understand themselves and believe that their true selves are worth defending, in much the same way that all of us resist these sorts of pressures in the real world. But using fantasy creatures allowed me to write some fun fight scenes, and I love to write fight scenes!

What was the writing process like for you? Did you always know you wanted this to be a middle grade novel?

Writing A Game of Fox & Squirrels was one of the most rewarding projects I’ve ever undertaken, and I wanted to keep the therapeutic ball rolling in Every Bird a Prince by exploring aromanticism and asexuality, identities that I wish I’d known about as a kid. These identities can be particularly hard to figure out at this age because many young people are also encountering puberty around the same time, and puberty is an apocalypse of confusion on so many fronts. It can be very difficult to sort out one’s truth from the onslaught of messaging kids are bombarded with daily.

I think a lot of young readers have heard of aromanticism and asexuality at this point, but if they haven’t, I want this book to give them that language, so they at least know it’s an option. When I talk with my friends in the ace community, “I wish I’d known” is a common refrain. Words—and identity labels—have power, and I knew I wanted to empower middle grade readers in this specific way.

The term “prince” is usually associated with masculinity; why did you choose it for the animals who do not have any gender distinction in this world?

I deeply dislike the gender-ization of job titles. I don’t like “prince” and “princess” any more than I like “actor” and “actress” or “author” and “authoress.” I could have chosen other words entirely, but I wanted to evoke the mythic sense of fairy tales, and in Western literature at least, fairy tales are riddled with monarchies. We hear the word “prince” in the context of a story and images of castles and fancy clothes and magic spring to mind. I wanted those associations! And I especially wanted my birds to wear little crowns, because… how could I not? But the truth is, I am uncomfortable with the idolization of monarchies and how prevalent they are in our stories for young readers.

In Every Bird a Prince, I wanted princes but no kings or queens, and no serfs or peasants or nobility of any other rank. Every bird is equal, and every bird is royalty—because that’s how I want us to view ourselves. We are all worthy of that honor and respect. One family isn’t born special, we all are.

And we should all get to wear crowns whenever we want.

The bird Prince Oriti-ti shares some pearls of wisdom, such as “when the strength flows from you, not to you, then no one can take it away.” Why were birds your choice of animals to be important characters throughout the story?

I had an encounter with a bird when I first moved to Oregon. Less than a week into owning my first house, a cedar waxwing flew into my glass sliding door and was stunned (the bird was fine, don’t worry!). I panicked, called the local wildlife center, and put the bird in a box to recover for a few hours. When I finally opened the box, that bird glared at me, gave me a stern talking to, and then flew away in a huff. I knew they would someday be a character in one of my books.

Birds are fragile, but they’re fierce. They’re often caged, but will forever represent freedom. Plus, birds are everywhere. Most readers will have fed a pigeon or seen a songbird at a feeder or run away from a goose. I loved the idea of these tiny colorful creatures facing off against overwhelmingly larger and more vicious foes.

Initially, Eren’s whispered thoughts to herself are primarily negative self-talk such as, “I did this to myself. This is what I deserve,” and “I’m the one who should be surrendering.” How do these thoughts shift as Eren grows and changes throughout the novel?

The sad fact is that we will never stop hearing the whispers. It’s something I talk about in the book, and something I certainly experience as an adult. We can defeat our personal “frostfangs,” but they’ll always return. The best thing we can do—and this is what Eren learns to do—is to begin questioning whether these whispers are actual truth, or just doubts and fears from ourselves or others. We can’t stop hearing the whispers, but we can stop listening to them. As Eren begins to understand and believe in herself, she’s better able to resist their effects. In short, she starts developing better coping strategies…which is often the best we can do for the sorts of battles that never end.

Read More: 4 Middle Grade Novels About LGBTQIA+ Lives Across Time

Eren finds her weapon of strength to fight the frostfangs with her bike, and Alex finds strength with his ukulele and singing. What or where would you summon your strength from?

Ha! That’s a great question. I think some of my answers might be a little more personal than what I’d like to admit in this interview, so I’ll simply say art. I wanted to be an artist since I was a little kid, and it still brings me tremendous joy to draw little birds with crowns, or even to use graphic design to create stickers and bookmarks. If I could attack the frostfangs with my knowledge of fonts and kerning, I’d be invincible!

Prince Oriti-ti says, “Fear may be contagious, but so is bravery.” What can readers learn from your book about bravery and battling their fears?

I’m hesitant to say I’m trying to teach anything explicitly, but I would be thrilled if readers found strength in any of these ideas:

1) That almost everyone hears “whispers.” Not just us, but also our peers and parents and teachers, our heroes and our enemies. We all have our battles.

2) That some days you might lose the fight against the whispers, and that’s okay.

3) That the best way, and maybe the only way, to “fight” these whispers is to anchor in our truths. To know ourselves and find strength in that knowing.

4) That knowing our own truths often helps others to find theirs.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!