Up Close and Personal with Children's Book Artists

Educators use picture books regularly for a variety of purposes, but how often do we challenge students to think about the reasons the book exists, how the artist's background informs his or her perspective, and why particular media are chosen or certain design decisions are made? Exploring these and other questions through the vast array of possibilities on reputable websites will provide insights and meaning for students of all ages and enliven lessons across the curriculum.

Process

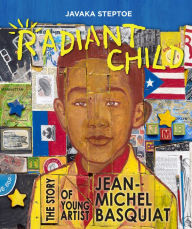

Javaka Steptoe

Many elements of the book contribute to the success of Javaka Steptoe’s 2017 Caldecott winner, Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat (Little, Brown, 2016), including the impact of the layered collage images and the sense of fragmentation produced by the cracks between the pieces of wood employed as canvas. These choices relate stylistically and psychologically to the book’s subject. Students can learn just how this works by watching part or all of the 44-minute Steptoe entry in the New York Times’ video series, Children’s Books Live Illustration.

As the New York Times children’s book editor, Maria Russo, interviews Steptoe, he creates a new Basquiat piece in the style he employed for the book. Although viewers are not able to see the artist’s face (the camera captures an aerial view of his hands at work), the process is riveting. Nothing is more indicative of his quest for excellence than the time he devotes to repositioning the blocks, searching for the fit that feels right. Before the pieces are attached, Steptoe starts applying white and then blue acrylic paint, creating an alluring sky. With scissors and X-acto knife, he cuts a cityscape from a Xeroxed page, removing pieces and re-assembling them into a more interesting composition against the blue background. Using tracing paper, the artist draws Basquiat wearing boxing gloves, an image that becomes a stencil that he traces and fills in against the urban backdrop.

Russo, clearly surprised, inquires several times about the security of the wood blocks. Early on, he replies: “You never know when you’re going to change a piece.” Toward the end, he drily states: “I’m going to train 'em like a puppy.”

As the piece magically transforms, Steptoe discusses growing up with his famous father, the commonalities with and inspiration he derived from Basquiat, and thoughts about his own approach to art: “I feel like I’m in a buffet when I see other artists’ work. It might or might not fit into what I need at the moment, but I store it away.”

Offering food for thought on the relationship between process and subject matter, this video would be an illuminating follow-up to a reading of Radiant Child for elementary aged children through high school. More than videos comprise the growing series, highlighting artists such as Mark Siegel, Jerry Pinkney, Sophie Blackall, Christian Robinson, and Vera Brosgol.

David Wiesner

On David Wiesner's website has, among other things, a link to his blog. It is on this page, designed with 23 intriguingly illustrated and captioned rectangles, that kids can chart a serendipitous route through the artist’s life, art, and musings. Some may want to start at “The Beginning,” a description of the artist's entrée into a career as a children’s book creator.

After a class at the Rhode Island School of Design taught by guest lecturer Trina Schart Hyman, Weisner was invited to submit a cover painting and interior drawing for Cricket magazine, where Hyman was the art editor. As in all of Wiesner’s blog entries, this one provides original art and pithy, witty commentary.

“Oops” chronicles his mistakes, including the multiple attempts he made to get the sky right for the final page of Caldecott winner Tuesday (Clarion, 1991); this topic is a favorite during school visits. In “Phone Home,” lured by an image of E.T., kids will learn that in 1984, the artist was invited to Universal Studios to work with Steven Spielberg and others to produce a storybook about the beloved character. Images include a sketch by the famous director. In addition to a fine high school photograph of Wiesner on the JV basketball team, “Hello, Dali!” describes the time he missed a scrimmage to go on an optional field trip to the Museum of Modern Art to see one of his favorite paintings, Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory. For an in-depth look at the sketches and paintings that led to pages in Mr. Wuffles (Clarion, 2010) and Art and Max (Clarion, 2013), readers can click on the “Creative Process” tab on his homepage. In addition to learning why an illustrator makes particular creative choices, students will acquire a much deeper understanding of the research, revisions, and sheer labor involved in making a distinguished picture book, as well as the rewards.

Point of View

Yuyi Morales

For a sense of Yuyi Morales's passions and devilish sense of humor, start with the artist's website. There readers will find quotes and drawings by children, activities related to Kathleen Krull’s Harvesting Hope (Harcourt, 2003), and Lucha mask patterns to accompany Niño Wrestles the World (Roaring Brook, 2013). But perhaps best of all are the artist’s many YouTube videos. These offer a chance to delve into her point of view while literally hearing her voice—a wonderful opportunity to ask children: What in her background has contributed to the themes and styles found in her books?

In her most recent video, “dreamers,” (10/22/17) Morales speaks poignantly about her moves between America and Mexico: “I feel like I am a constant immigrant.” While people in the children’s literature realm may know her story of moving to California from Mexico as a young mother, and learning to speak English in the public library while reading to her baby, children will be hearing it for the first time—and her presentation from home (now back in Mexico) has added resonance in the current political climate. The videographer begins filming inside Morales's colorful, art-filled house. He then walks through her garden, filled with hanging vines, abundant greenery, and flowers. Finally, viewers see Morales in her studio, where she is working on her new book, Dreamers, scheduled to be published by Neal Porter Books/Holiday House in September.

The artist talks about searching for the simplest way to portray “what it’s like to grow by the hands of a lot of people extended to you in the United States” as was her family’s experience. That she is now creating a picture book—the format that was both tool and inspiration for so much of the growth encountered in her new land—is a lovely symmetry. This six-minute film is a provocative study on perspective.

Shaun Tan

Secondary school students are often required to analyze political speeches or historical documents to discover how rhetoric is used to advance a point, and how the style and content contribute to the persuasiveness of a text. What if one of the speeches chosen was penned by a children’s or young adult author? Shaun Tan, perhaps best known for his groundbreaking graphic novel on immigration, The Arrival (Scholastic, 2007), has written and delivered a number of speeches.

In May 2001, his paper at the Australian Literacy Educators’ Association conference addressed "Originality and Creativity.” Examining Tan’s illustrations of John Marsden’s The Rabbits (Simply Read, 2003) and Tan's The Lost Thing (Simply Read, 2004) would offer invaluable context for decoding and commenting on the speech. Tan begins with a notion attributed to Paul Klee, who once described an artist as being "like a tree, drawing the minerals of experience from its roots—things observed, read, told and felt—and slowly processing them into new leaves.” He continues by referencing paleontologist Stephen Jay Gould, who wrote, “the greatest discoveries are to be found not in a freshly hewn cliff of shale, but in old museum collections, by rethinking the relationships between the objects that have already been archived in our knowledge.”

Tan clarifies his interest in these ideas by writing: “Often the most interesting stories are ones which tell us things that we already know but haven’t yet articulated in our minds.” On first reading Marsden’s story of colonization, Tan struggled with how to illustrate it. He comments: “the image of Beatrix Potter bunnies with redcoats, muskets and British flags was not going to work.” Tan discusses his research of items as disparate as tree kangaroos, antique furniture, and industrial architecture—as well as the snippets of historical and literary sources that percolated in his brain while creating the final art. In the end, he realized he had to “build a parallel story of my own…something to react with it symbiotically.” A similar process, involving 1930s issues of Popular Mechanics, his dad’s old chemistry textbooks, and a Hieronymus Bosch painting helped him design The Lost Thing. Students familiar with extracting and transforming information and ideas from a variety of sources to create their own identities and projects will find something of interest here in the content—and that can go a long way in helping critique go down.

Obstacles

Ed Young

Since learning often involves struggle, problem solving, and do-overs, it can be comforting for students to know that even the very successful go through these stages. Ed Young describes one such struggle in a video conversation (November 18, 2008) about illustrating Mark Reibstein’s Wabi Sabi (Little, Brown, 2008); Young delivered the art for this book to his agent’s doorstep, only to learn it disappeared. This was original art—there were no backup copies.

Giving up did not seem to be a consideration; rather, the artist talks about how the “uneasiness” of the situation helped him ponder what in the art could be improved. The title of the book is a concept born in Chinese Taoism, then borrowed by the Japanese, the culture in which this story of a cat in search of her name’s meaning is set. Young defines wabi sabi as “seeing beauty in things not noticed by ordinary vision.” It’s a state of mind. And it's one the artist inhabits, as exhibited by the paint-soaked T-shirt scrap used to create a warm, textured background in the new art.

In the video, Young walks past the series of tables against the wall of his studio, displaying the new sequence of pages—pointing out the leaves, grasses, and other natural materials in use, “better than what you can buy,” he notes. The book is exquisite, but the artist’s understated acceptance of the unfortunate art loss and positive attitude is possibly more exceptional. Both book and video will speak to a wide span of ages. In a somewhat anticlimactic denouement to his saga, the missing art was discovered in a local church months later.

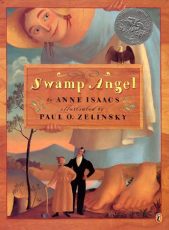

Paul Zelinsky

Another Caldecott winner who is no stranger to problems is Paul Zelinsky. It's worth digging around in your periodical portal to access M. P. Dunleavey’s “The Bedeviled Swamp Angel” from the November 28, 1994 issue of Publishers Weekly (pp. 30-1). Anne Isaac’s tall tale features Angelica Longrider, who as a baby was “scarcely taller than her mother” and who grew up to outperform all the men in Tennessee in dealing with the terrifying bear, Thundering Tarnation.

Upon reading the text, Zelinsky envisioned the art in oils, in the style of primitive paintings rendered on wood veneers. To see what he was imagining, visit the National Gallery of Art’s website. Go to the “Collection” tab, and click on “Search the Collection,” and filter by medium (painting), nationality (American), time span (1775-1900), and style (naïve). The PW article outlines the series of disastrous events related to Zelinsky’s decision. The artist had seen cherry-colored, wood-grained paper in an art supply store, but the distributor was out of business. When the elusive paper was finally procured, he sent it to the Hong Kong printer to make sure the wood was flexible enough to fit around the machine’s cylinders—it was.

The next batch kept curling up, so Zelinsky took it to a framer to have it dry mounted, but it was ruined when it was bent the wrong way. A UPS strike and snowstorm delayed another delivery, dashing hopes of meeting any sales or show deadlines with finished paintings. The saga continues, but the ultimate catastrophe was relayed in a fax from the printer who said the finished paintings were covered in little white fibers. The packing material had stuck to the varnish! Happily, a savvy conservator back in New York was able to help.

Zelinsky remarks: “I was verging on apoplexy. But with each thing that happened I felt much more determined not to let it stop me.” Swamp Angel (Dutton, 1994) garnered many accolades, including the New York Times Best Illustrated Book of the Year and a Caldecott Honor. The art glows with a rich woodsy warmth, perfectly suited to this backwoods tale. What if the artist had given up and used crayon or pencil, the media his editor had originally pictured? What do your students think?

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Darrel Pontejo

In choosing the right book, they must also take into consideration the content of it and also the lessons the kids will learn in reading those and the kids age. https://academyforhealthsuperheroes.com/choose-right-childrens-book/Posted : Apr 30, 2018 01:25