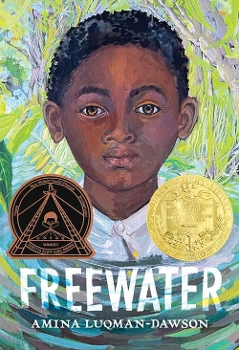

Amina Luqman-Dawson: The 'Extraordinary Experience' of Researching, Writing 'Freewater'

Research provides an opportunity to reclaim the narrative of enslavement and “share it in creative ways that deeply connect us to the past,” says the author of Freewater, which won the 2023 Newbery.

|

Photo by Zachariah Dawson |

Other authors on researching Black history: |

Amina Luqman-Dawson describes writing Freewater (Little, Brown, 2022), her Newbery Award–winning novel about siblings who flee slavery to discover freedom, as an “extraordinary experience,” even in the face of research obstacles.

Her middle grade novel draws inspiration from the Maroons of the Great Dismal Swamp, formerly enslaved people who found ways to survive in the wilderness. (During the 18th century, enslaved Africans who had escaped their enslavers were referred to as Cimarrones or Maroons.) To portray this accurately, Luqman-Dawson had to delve into various topics, such as the indigenous terrain, flora, fauna, and animals encountered by Maroons.

“The challenge that all historical fiction writers who focus on African American history face is that the voices of enslaved and often free Black people were deliberately silenced,” says Luqman-Dawson, who also won the Coretta Scott King Author Award for Freewater.

Fortunately, Luqman-Dawson could look to the work of Dr. Daniel Sayers, an anthropologist whose archaeological studies illuminated Maroons’ lives and survival strategies. In an interview for the National Endowment for the Humanities magazine, Sayers once said that in creating a “social and economic world of their own,” the Maroons embody “the civil rights, occupy, and labor movements all rolled into one.”

Luqman-Dawson, who learned about Maroons’ survival strategies, culture, and significant historical figures, also considered research from Sylviane Diouf, an award-winning historian of the African Diaspora. Diouf focused on the lost stories of American Maroons in Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons (NYU Press, 2014). The book examines individuals and groups that “settled in the wilderness, lived there in secret, and were not under any form of direct control by outsiders.”

Luqman-Dawson, who learned about Maroons’ survival strategies, culture, and significant historical figures, also considered research from Sylviane Diouf, an award-winning historian of the African Diaspora. Diouf focused on the lost stories of American Maroons in Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons (NYU Press, 2014). The book examines individuals and groups that “settled in the wilderness, lived there in secret, and were not under any form of direct control by outsiders.”

According to Luqman-Dawson, the Maroons’ secrecy led to their success, but interestingly, their presence is well-documented in historical records. “The existence of Maroons in the American South meant a loss of capital and labor, and because of the threat to order they posed, there are records noting their presence, the nuisance they created, and government measures used to deter and capture them,” she explains.

Although Freewater is a work of fiction, some of its characters, such as the “heroic marauder, Suleman,” are based on actual accounts of what Luqman-Dawson describes as “outright rebellious behavior and theft of plantation food and other items by Maroons.” In Jamaica, historical records indicate that the Maroons fought against the British army for many decades, ultimately winning peace treaties in the early 1700s, which granted them sovereignty in certain territories.

Luqman-Dawson says her character Mrs. Light, a leader in Freewater, was inspired by Queen Nanny, a leader of the Maroons of Jamaica. A 2015 documentary film, Queen Nanny: Legendary Maroon Chieftainess, created by Roy Anderson and Harcourt Fuller, showcases the struggles of the Maroons. However, according to the film’s synopsis, most of what is known about Queen Nanny comes from folklore and oral history.

That highlights how the limited ability of many enslaved people to document their own stories in writing spurred an oral storytelling tradition that helped preserve some of their histories. Authors sometimes use interviews with community members and family elders to document historical events. However, verifying specific details can still be challenging.

Luqman-Dawson suggests that connecting with like-minded historians can help maintain motivation. She advises authors not to be discouraged by the fact that the voices of the enslaved have been silenced. Instead, she views it as an opportunity to reclaim the narrative and “share it in creative ways that deeply connect us to the past.”

For example, in Freewater, Luqman-Dawson used elements of magical realism to engage readers’ imaginations. She embraced what she describes as “grand, big storytelling” (like having a sky bridge leading to the Freewater Maroon community) to make readers “desire the impossible—to want to visit a time of enslavement.”

Luqman-Dawson also has some inspirational advice for authors who aspire to tell these and similar kinds of stories. “Remember, there is no tale you could spin, nor magic you can inject that will outshine the reality of the strength, ingenuity, and courage these ancestors demonstrated.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!