Making Informed Choices About Nursery Rhymes to Share—or Not

Understanding the racist roots of nursery rhymes can help librarians and early childhood educators decide what is appropriate to share with children—and what should be left behind.

Nursery rhymes, on the surface, seem innocuous enough. What, after all, could be more innocent than the rhymes we use when bouncing babies on our knees? But even the slightest scratch beneath the surface is enough to reveal that not all nursery rhymes are created equal. Some trace their origins to racist rhymes. Some were never racist. And some didn’t originate as racist but were appropriated by a racist culture later. As a result, how is the average reader to know which are worth telling to their children and which are best avoided? And when you are a librarian doing a story time for babies, toddlers, or preschoolers, which rhymes should be in the roster and which must be jettisoned?

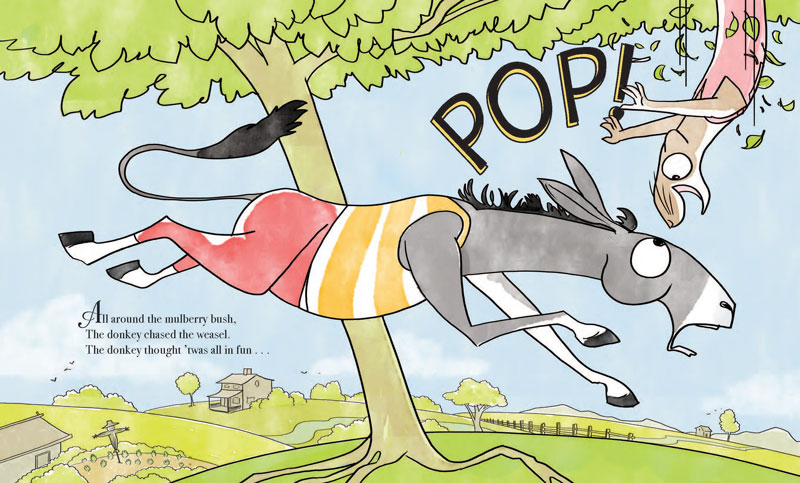

As I wrote my fractured nursery rhyme picture book, POP! Goes the Nursery Rhyme, I encountered just this problem. I wanted to include only those rhymes that were appropriate. Unfortunately, nursery rhymes prove surprisingly difficult to research. While countless academic texts wax poetic on fairy tales, nursery rhymes are another matter entirely. Few books research their origins, and fewer still are concerned with their larger implications. Yet there are great advantages to knowing your nursery rhymes well. If you have a firm grasp on the history, you can avoid perpetuating racist rhymes, particularly if those rhymes once had connections to minstrel shows.

Remnants of this type of performance can be found in unexpected places to this day. For example, not too long ago, I visited a Wisconsin museum of which I am very fond called the House on the Rock. The lifeblood of the House is its collection of moving exhibits—automatons, coin-operated mechanics, etc. In one section, you can watch a series of small exhibits that were once created for the window displays of a diamond dealer. Some of them feature the verses of nursery rhymes, and one in particular caught my eye. I looked. I blinked. I peered closer. Though the figures in the piece were ostensibly white, the nature of the piece itself (top hat, white gloves, etc.) made something infinitely clear. You’ve heard of whitewashing the past? This was literal whitewash placed over what were undeniably minstrel figures. It wasn’t obvious unless you looked closely, but once noticed it was impossible to ignore. In a twisted way, it was a rather perfect encapsulation of how white America tries to hastily paint over our painful past without letting go of it in any significant sense. And there’s no better example of this tendency than in nursery rhymes.

|

A look inside Pop! Goes the Nursery RhymeIllustration by Andrea Tsurumi |

The connection between the minstrel figures and nursery rhymes constitutes a long-standing relationship in America. Many minstrel shows either created or appropriated classic nursery rhymes in different ways. This perverse twisting was no innocent accident. As Ginger Mullen’s 2017 article in Journal of Childhood Studies reports, we now know that nursery rhymes serve to not only support language and cognitive development but to also develop the skills that allow children to communicate in socially and age-appropriate ways. Little wonder that after the Civil War, white people seeking ways to inculcate the young in a racist overview found nursery rhymes to be the perfect vehicle for anti-Black rhetoric. Worse, some rhymes were originally created with racist verses, those words only changed later to hide their shameful past.

None of this is news to Black readers and educators. While the idea that a number of nursery rhymes have racist origins may surprise their white counterparts, that ignorance is a privilege not everyone is granted.

Edith Campbell, former teacher and current academic librarian, shares a relatively recent incident that highlights how nursery and schoolyard rhymes can appear in the library or classroom in harmful ways.

“When I taught at a K–8 school in Indiana where all the students were Black and most of the teachers were white, one of the white teachers had her students perform ‘No More Monkeys Jumping on the Bed’ [“Five Little Monkeys”] for the entire school to see. Black teachers were livid. It didn’t happen again.”

In the Reader’s Digest piece, “8 Children’s Nursery Rhymes That Are Actually Racist,” author Eisa Nefertari Ulen breaks down a number of rhymes, explaining, for example, that “Eeny Meeny Miny Mo” wasn’t catching a tiger by its toe in the original derivation but a particularly offensive slur. When it comes to offensive nursery rhymes, of course, the true number is far higher than eight. How high can it be? That has yet to be determined. As Franklin Hughes, a representative at the Jim Crow Museum, points out, we’re always learning. In fact, the current work by universities to digitize once-forgotten music has yielded a plethora of information.

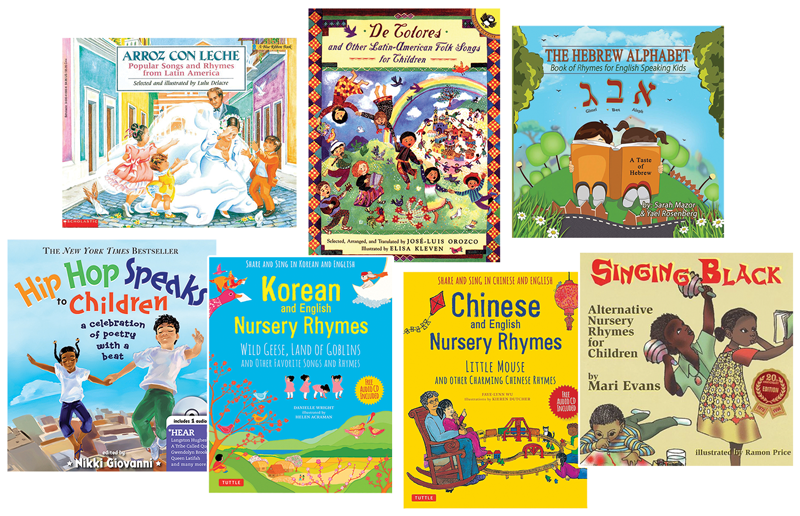

Rhymes for Modern TimesHere are some nursery rhymes alternative collections to consider including in your library.

Arroz con Leche: Popular Songs and Rhymes from Latin America by Lulu Delacre De Colores and Other Latin American Folk Songs for Children by José-Luis Orozco, ill. Elisa Kleven The Hebrew Alphabet: Book of Rhymes for English-Speaking Kids by Yael Rosenberg and Sarah Mazor Hip Hop Speaks to Children: A Celebration of Poetry with a Beat edited by Nikki Giovanni Korean and English Nursery Rhymes: Wild Geese, Land of Goblins and Other Favorite Songs and Rhymes by Danielle Wright, ill. Helen Acraman Little Mouse and Other Charming Chinese Rhymes by Faye-Lynn Wu, ill. Kieren Dutcher Singing Black: Alternative Nursery Rhymes for Children by Mari Evans, ill. Ramon Price |

“The more we discover from the tunes and lyrics from songs of yesterday, the more we see these songs have influenced music and rhymes we know today,” he says.

The Jim Crow Museum, located in Big Rapids, MI, at Ferris State University, describes itself as “the nation’s largest publicly accessible collection of artifacts of intolerance. The website goes on to state, “The Museum contextualizes the dreadful impact of Jim Crow laws and customs [and] uses objects of intolerance to teach tolerance and promote a more just society.”

With an extensive collection, the museum is an excellent resource for researching individual rhymes. Take “Pop Goes the Weasel,” for example. The rhyme originated in England in the 1850s (this according to the book Pop Goes the Weasel: The Secret Meanings of Nursery Rhymes by Albert Jack), but did it have a racist version in the United States? The museum was quick to find one such example. In 1855, a collection of songs for the piano was released with the title Pop Goes de Weasel. Franklin Hughes explained in an interview that, “the dialect is definitely broken and the lyrics in the second and third stanzas make direct political and social commentary to the times. For instance, the second verse says:

“John Bull tells, in de ole cow’s hum,

How Uncle Sam used Uncle Tom,

While he makes some white folks slaves at home,

By ‘Pop goes de Wesel!’”

Some may think the rhymes that originated in racism or are inculcated in it are in the past and that if kids today don’t even understand the references, there is no reason to worry.

But consider not only Campbell’s example of “Five Little Monkeys,” but also the librarians who sing familiar rhymes and songs during story time. There is value in knowing these chants’ histories. That goes for caregivers as well. In wrestling with this very issue, a December 2023 story in Parents by Hannah Nwoko noted that “understanding problematic conditioning, even when it is couched in nostalgia, is key to raising liberated children.”

The article then called out those specific rhymes that started out as racist, including “Eeny Meeny Miny Mo,” “Do Your Ears Hang Low,” “Jimmy Crack Corn,” and “Camptown Races.”

“Though their words have been modified, the recognizable melodies of these nursery rhymes are still a scar to the Black community and a stark reminder of the trauma inflicted in the very recent past,” Nwoko wrote.

In her Reader’s Digest article, Ulen pointed out that changing the racist slur in the original title of “Five Little Monkeys” to “monkeys” actually reestablished the original racism rather than erasing it.

So should we attempt to save such rhymes?

“Rather than trying to save them, we need to study them,” says Campbell. “Find out what they mean and what they represent from a historical perspective. So many of us don’t want to talk about race; it makes people so uncomfortable.

“But if we begin to talk about the nursery rhymes, the hidden histories, the laws, even who we consider beautiful, then we can begin to question and hopefully eliminate some of the oppressive policies and practices. The more we have these conversations, we can get rid of feelings of guilt, embarrassment, anger, and whatever else and begin to make progress.”

Campbell is right that talking about race, particularly in nursery rhymes, has historically been an unpopular notion. As of now, there is no annotated book of nursery rhymes with a strict focus on their place in the pantheon of race and racism in America.

Knowing that there are a plethora of nursery rhymes sullied by racism, the best that anyone can do is to acknowledge that fact from the start. Do what research you can. Know what you don’t know. Then determine how you can do better.

Some nursery rhymes are beyond the pale, while others are free from problematic content. If you wish to continue to use them in story times, it is important to determine which is which. Institutional racism permeates every aspect of American culture, and our story times—especially our story times—are worth examining more closely.

Betsy Bird blogs at “A Fuse #8 Production” (slj.com/Fuse8).

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!