Beyond Tradition: Recent Jewish-themed Books Show Diversity of Characters and Genres

Fantasy or contemporary, funny or serious, these books show characters of different cultural backgrounds, skin colors, and gender identities, demonstrating the many ways in which Jews can be intersectional.

|

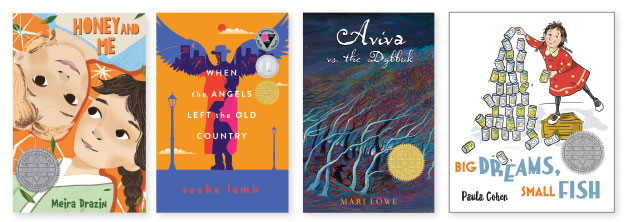

From the left: Meira Drazin; Arthur Levine; Michal Babay; Danielle Joseph; R. M. Romero. |

When Meira Drazin looked for Jewish books growing up, she found Holocaust novels and the “All-of-a-Kind Family” series. “Those were the only representations of observant Jewish families that I read,” she says.

When Meira Drazin looked for Jewish books growing up, she found Holocaust novels and the “All-of-a-Kind Family” series. “Those were the only representations of observant Jewish families that I read,” she says.

That experience stayed with Drazin when she started writing for children. At first she wrote stories like the mainstream books she’d grown up with—those without Jewish characters—but they didn’t feel right to her. She had an image in her head of “two girls sitting on a bus, religious, and suddenly everything just crystallized. Because I imagined them in a religious community, I just suddenly knew all kinds of things about them,” she says. “I knew about their school and I knew about their family, and I knew that one family was slightly more religious than the other, and I knew what kind of camp they went to and what kind of shul [synagogue] they went to, and I could imagine their houses.”

That vision led to her middle grade novel, Honey and Me (Scholastic, 2022), about two sixth-grade friends in a close-knit Jewish community.

Jewish representation in children’s books can’t just be about holidays, the Holocaust, or antisemitism, say authors and publishers. Increasingly, writers are telling different types of stories—fantasy or contemporary, funny or serious—about characters who happen to be Jewish. And they say it’s important to show Jews of different religious levels, skin colors, cultural backgrounds, sexual orientations, or gender identities, demonstrating the many ways in which Jews can be intersectional.

Arthur Levine, founder of Levine Querido, says its mission is “battling against the phenomenon of the ‘single story’ for any historically marginalized group. We don’t want every book about Black people to be about slavery and sorrow, and we don’t want every Jewish book to be about the Holocaust or Hanukkah. Because there’s more to any marginalized identity than the single most heavily identified story about that group.”

Three of Levine Querido’s Jewish-themed books published in 2022 won recognition at the 2023 American Library Association Youth Media Awards: When the Angels Left the Old Country by Sacha Lamb won the YA categories of the Stonewall Book Award and Sydney Taylor Book Award and was a Printz Honor title; Aviva vs. the Dybbuk by Mari Lowe was the Sydney Taylor middle grade winner; and Big Dreams, Small Fish by the late Paula Cohen took a Sydney Taylor picture book honor.

“Each book featured different kinds of Jews and different times of history,” Levine says. “It’s the variety itself that connects them and the excellence of the storytelling.”

Heidi Rabinowitz (right), librarian and creator of the Book of Life podcast about Jewish children’s literature, says, “Jewish readers feel validated when we see Jewish characters participating in the life of the larger community, and non-Jewish readers are reminded that we are an integral part of the fabric of our society.”

Though authors like Judy Blume have offered exceptions—Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret. famously depicts an interfaith family—that representation hasn’t always been available with Jewish books.

Emily Barth Isler, author of the middle grade novel AfterMath (Lerner, 2021), says that when she was given Jewish-themed books as a child, “I remember feeling frustrated that those books were always just about the characters being Jewish.” Isler, who was raised Reform, didn’t see her experiences in books. In series like “Little House on the Prairie” or “Anne of Green Gables,” the characters were Christian by default. “It felt really isolating,” she says.

For much of Levine’s time in publishing, he says, most Jewish picture books were folktales set in 17th-century Poland—which were important, but as a young Jewish queer man, he didn’t see himself in those stories.

Fantasy authors had similar difficulties. Growing up, R. M. Romero, author of the YA novel in verse The Ghosts of Rose Hill (Peachtree, 2022), mostly saw Jewish fantasy stories in folklore collections or books like Eric Kimmel’s Hershel and the Hanukkah Goblins.

“I think Jewish fantasy is having a renaissance right now,” she says. Along with Lamb, Rebecca Podos (From Dust, a Flame; HarperCollins, 2022), Aden Polydoros (The City Beautiful; Inkyard, 2021), Rena Rossner (The Light of the Midnight Stars; Redhook, 2021), and Ava Reid (Juniper & Thorn: A Novel; HarperCollins, 2022) either feature Jewish characters or base their work on Jewish folklore, and several feature

LGBTQIA+ characters as well.

Rabinowitz advocates for better Jewish representation in all types of stories, through her podcast, her blog, and her 2022 guide for the Association of Jewish Libraries, “Evaluating Jewish Representation in Children’s Literature” (based on a similar guide by Muslim librarians). She says Jewish representation used to be almost “snuck in,” as in the offhand Yiddish words in Lemony Snicket’s “A Series of Unfortunate Events.” In the past few years, Rabinowitz has seen more casual Jewish representation and authors displaying it more comfortably.

|

From the left: Emily Barth Isler; Sarah Mlynowski; Yevgenia Nayberg; Barbara Krasner; Chris Baron. |

Drazin also observes a greater variety of Jewish stories now, including Isaac Blum’s The Life and Crimes of Hoodie Rosen (Philomel, 2022), which depicts in part the everyday life of an Orthodox community and won the William C. Morris Award this year.

Sarah Mlynowski, whose novel Best Wishes (Scholastic, 2022), features a Jewish protagonist, was inspired to write by the work of Blume and fellow Canadian Jewish author Gordon Korman, whose books like Don’t Care High (Scholastic, 1986), occasionally feature Jewish characters. “I remember the feeling, really, of seeing myself in those books. And it gave me the confidence to assume that a girl like me could become a protagonist and writer.”

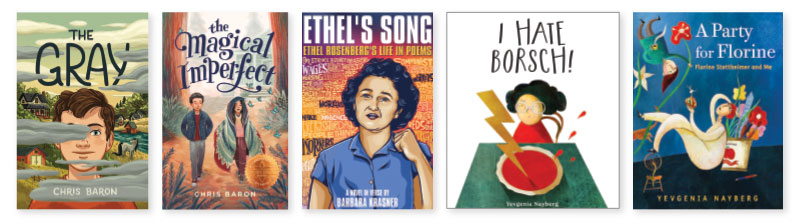

The stories Jewish authors are telling vary widely. Romero’s The Ghosts of Rose Hill is about a young violinist who falls in love with a ghost in a forgotten Jewish cemetery in Prague. Drazin’s Honey and Me, which won the Sydney Taylor Manuscript Award, is about a girl trying to escape her charismatic best friend’s shadow. Chris Baron’s The Magical Imperfect (Feiwel & Friends, 2021), a Sydney Taylor Notable Book, follows a silent boy who befriends a girl dealing with medical issues. And Danielle Joseph’s Sydney A. Frankel’s Summer Mix-Up (Kar-Ben, 2021) is about best friends switching identities.

Isler’s AfterMath, winner of the 2022 Mathical Book Prize, is about a girl coping with her brother’s death who moves to a town that is recovering from a school shooting. American culture tends to ignore survivors of all types, Isler says, and she wanted to write about the idea of “so many Jews I know, including my grandparents, my grandparents-in-law, who went on to make beautiful, meaningful lives even though they had been through trauma.”

In nonfiction, Barbara Krasner’s YA novel in verse, Ethel’s Song: Ethel Rosenberg’s Life in Poems (Astra, 2022), tells Ethel’s side of the spy couple’s story. “She was caught up in place and time and circumstance,” says Krasner.

Other forthcoming nonfiction stories include Joseph’s Ruth First Never Backed Down (out in the fall from Kar-Ben), a biography of South African freedom fighter Ruth First; and Yevgenia Nayberg’s A Party for Florine (Holiday House/Neal Porter, 2024) about the artist Florine Stettheimer.

Upcoming fiction is equally varied. Romero’s next novel, A Warning About Swans (Peachtree, July 2023), centers on a swan maiden who can bring dreams to life. Baron’s forthcoming The Gray (Feiwel & Friends, June 2023), tells of a boy learning to live with his anxiety. Michal Babay’s On Friday Afternoon (Charlesbridge, summer 2023), is about getting ready for Shabbat.

Romero, whose novel features a Jewish Latina protagonist, wants to see more Jewish characters who are diverse, “rather than ignored or sort of lumped in with, ‘all Jews are white,’” she says. While groups like We Need Diverse Books have focused more on Jewish representation, there’s still an assumption that all Jews are Ashkenazi (of European descent), Romero says. “But that is changing in a good way, I think.”

Rabinowitz agrees that more books are needed about Sephardic Jews (of Spanish/Portuguese descent) or Mizrahi Jews (of North African/Middle Eastern descent).

Jewish publishing companies like Kar-Ben Publishing are trying to address the need for more diversity. Kar-Ben, founded in 1974, focuses on all aspects of Jewish culture, says publisher Joni Sussman. For instance, Shoham’s Bangle, by Sarah Sassoon and Noa Kelner, centers on an Iraqi child whose family must leave their belongings behind when they move to Israel—but her grandmother secretly bakes their bangle bracelets into the pitas they bring. “They’re taking part of their culture with them into their new lives. That’s a universal story,” Sussman says.

|

Martha Simpson, chair of the Sydney Taylor Book Award Committee |

Jewish readership ranges “from Orthodox Jews who are very, very observant, to very assimilated families, to families with one Jewish parent. We really want kids from all backgrounds to find themselves in a Jewish book,” she adds.

Those who are culturally but not religiously Jewish should be included as well, says Nayberg, author-illustrator of the picture book I Hate Borsch! (Eerdmans, 2022). Nayberg, who emigrated from the former Soviet Union in 1994, didn’t have religious traditions growing up because previous generations in the Soviet Union had needed to hide them. Now “the Jewishness of my books is being questioned because it’s not necessarily about Judaism” but about her immigration experience.

For instance, I Hate Borsch! (an alternate spelling of borscht) is about a young girl who despises the Eastern European soup until she comes to America and misses what she’d left behind. Anya’s Secret Society (Charlesbridge, 2019), a story of a left-handed person who finds other left-handed people after she emigrates, was intended as a metaphor for Nayberg’s experience growing up as the only Jew in school, then coming to the United States, where her differences don’t stand out as much. “But of course, everyone reacted to the literal topic of the book, which is what it is to be left-handed in a right-handed society.”

Jews from around the world have different stories, says Joseph, who’s from South Africa. With so much antisemitism, “it’s important that we showcase who we are,” especially for children who haven’t met someone Jewish.

Baron’s school visits have shown him the importance of his stories. Students in an Iowa school “had never read any book with Jewish characters. They had heard of Jewish holidays but they wanted to learn more about Jewish life,” he says. “I forget there are kids who don’t have Jewish kids in their class.”

Visual representation also matters, Rabinowitz says. Babay makes a point of requesting Jewish representation in illustrations for her books. For I’m a Gluten-Sniffing Service Dog (Albert Whitman, 2021), illustrator Ela Smietanka gave one character a Star of David necklace. In The Incredible Shrinking Lunchroom (Charlesbridge, 2022), Cohen showed a boy wearing a kippah. Babay has heard from parents and grandparents saying kids were “shocked and happy to see a kid wearing a kippah just like them.”

Her younger daughter was excited to see a Jewish character in one of Newbery-winning author Jerry Craft’s graphic novels: “There’s a Jewish kid in here, and he’s not the bad guy!” They emailed Craft to thank him, and he replied that he was “just so happy that [they] had said that.”

Sussman thinks the growing interest in Jewish books demonstrates a wider recognition for the Jewish community. The Association of Jewish Libraries became an affiliate of the American Library Association in 2010, and since 2019, the Sydney Taylor Awards have been presented during ALA’s Youth Media Awards announcements.

Offering more stories of casual Jewish representation also leads to more positive stories for young readers. Babay says, “I can’t imagine creating something and not having Jewish pride in it—Jewish joy.”

Writer and editor Marlaina Cockcroft has a passion for children’s books.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!