4 YA Authors Discuss Their #OwnVoices Debuts

Debut novelists Kiku Hughes, Jordan Ifueko, Syed M. Masood, and Christina Hammonds Reed talk about constructing their books with food, folklore, and family stories.

This month, four first-time novelists publish fiction that reflects real life, and the readers who need it. SLJ talked to Kiku Hughes, Jordan Ifueko, Syed M. Masood, and Christina Hammonds Reed about constructing their books with food, folklore, and family stories.

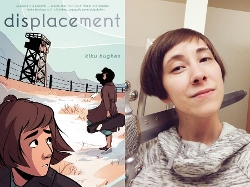

Kiku Hughes, Displacement (August 18)

Kiku Hughes, Displacement (August 18)

This is a graphic novel, but it’s inspired by your experience, and your main character shares your name. Can you talk about deciding to write this story as fiction rather than non?

I knew from the start that I wouldn't be able to make an entirely nonfiction book about my grandmother's experience in camp. She died long before I was born and never shared much about that time in her life, so I had to find a way to tell a story that wasn't reliant on exact details. Instead I wanted to focus on the overall experiences, the lasting impacts and the emotional baggage that was passed down through generations.

Tell us a bit about your process. What comes first for you, text or illustrations?

I like to start with a text outline of the whole book, then while writing the script I'll doodle page layouts in the margins, then finally turn those doodles into actual thumbnails and proceed from there.

Who is your ideal reader for this book?

This book is for everyone, but I would love it to be read by people who have never learned about Japanese American incarceration and who aren't particularly interested in politics. I hope it can get people invested in fighting the very current racist policies that are unjustly incarcerating minority communities today.

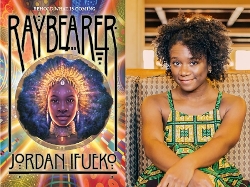

Jordan Ifueko, Raybearer (August 18)

Can you talk a bit about how you constructed the world of Raybearer?

I often describe Raybearer as the sum of my tangle of cultural influences. I'm the American daughter of Nigerian immigrants, who themselves were raised when Nigeria was a British colony, so there's loads of West African folklore, some Western fairy tale elements, and plenty of my own weird spice! I began writing the earliest version of Raybearer 's world in high school. My friend group was intimate, and we took our studies very seriously, so the idea of an intimate group of teenagers training to rule an empire blossomed from that! Almost every character in Raybearer is trying to figure out who they are. Some of them think they have it figured out, and the idea that they may be wrong makes them do horrible things. I think a lot of human conflict comes from the idea of identities being threatened.

You’re a longtime fan of comics and superheroes. Did any of those stories influence this book?

It's funny, I realized too late after describing myself as a comic book reader that few people share my definition of comic books. I never read superhero comics growing up, but would devour esoteric book collections of newspaper comics like Calvin and Hobbes. I loved Calvin in particular, because he was able to manifest his imagination in ways that I always fantasized about. I suppose it's natural that I starting writing fiction as a kid.

Who is your ideal reader for this book?

I genuinely hope that absolutely anyone could connect to the identity and relationship journeys in this book, but I often describe Raybearer as the book I wish I had as a kid. I was a Black girl bookworm in love with a genre—fantasy—that never loved me back. If there are other kids like me out there, I hope Raybearer is the mirror they've been looking for.

Read: July's Debut YA Authors Explore the Hidden Truths, Tropes, and Tragedies Behind Stories

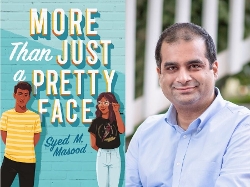

Syed M. Masood, More Than Just a Pretty Face (August 4)

Syed M. Masood, More Than Just a Pretty Face (August 4)

Food is a big part of Danyal’s story, and it can be a way of connecting with others. Do you consider yourself a chef?

Not at all! I’ve got a few signature dishes—my nihari, for example, is excellent thanks to a desi uncle I found on YouTube—but I’m definitely not a chef. I do love food though and I always have. I inherited that. My father would think nothing of driving a hundred miles to get to the best restaurant he could. So it is a family thing. We’re confirmed foodies for sure.

You also have a debut adult novel coming out next year. How does that experience compare with publishing your first YA book?

The differences are primarily in the writing process. When you’re writing an adult book, you can cut loose a little more with allusions and references. However, on some level, you’re usually writing about (or at least starting from) a place of discontent—either the discontent of the characters with themselves or the world as they find it. When you’re writing YA, your frames of reference are narrower, but your themes are more likely to be hope, discovery, and becoming. They are different kinds of freedom and I enjoy them both. The actual publication process is very similar. There are always minor differences from house to house, but there are no real surprises no matter which age group you’ve written for.

Who is your ideal reader for this book?

Can I say everyone? As an author, obviously, you want as wide an audience as possible.

But I think there are three different types of readers I specifically wanted to reach. First, for me always, are those Muslim readers who struggle with being told or being made to feel as if they’re not righteous or good enough. I wanted them to see that being flawed is okay. There are no perfect religious people, only people who pretend to be so. In the end, the measure of a soul is not outward, performative adherence to rules and laws, but the amount of love, kindness, and tolerance there is within it.

The second were more right-wing Muslims, of whom I was once one. I wanted them to see a story where a flawed Muslim character, one who sometimes even misunderstands religion, can still have a deep connection with the spiritual teachings of Islam. Just because you think someone is a “bad” Muslim doesn’t mean that they really are. Their inner journey might be worth admiring regardless. I wanted to remind them that, as Rumi said, “there are many paths to the Ka’aba” (the Grand Mosque in Mecca).

Finally, I wanted non-Muslim readers to get to see a spectrum of Muslim characters. It is a religious identity with which two billion people—that is a quarter of the world’s population—identifies. Yet in Western media there is one universal Muslim experience and it is an angry, sometimes violent, often oppressed, discontent experience. That simply isn’t true. There are all kinds of Muslims and in More Than Just a Pretty Face I got to show a few different types, for which I am grateful.

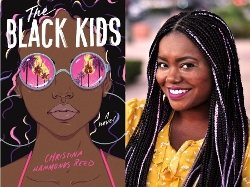

Christina Hammonds Reed, The Black Kids (August 4)

For many of us, the ‘90s don’t seem like long ago, but it is historical fiction. How did you bring this era to life for teen readers?

I have such a great love for the era having mostly grown up in the ‘90s. There was a definite nostalgia with which I approached shaping it on the page. That said, I was very young in 1992, I still had to do research and more fully immerse myself in all of the cultural references, music and movies. I spent a lot of time on YouTube. Many of the ‘90s songs I was listening to while writing made their way into the book. When we’re young, music is so important to our identity and we absorb pop culture like a sponge, so it was important for me to capture that part of adolescence. That said, while writing the specific is important, I also think there is something deeply universal about trying to figure out who you are and what kind of person you want to be that really transcends era, and so many of the issues that Ashley is struggling with remain super relevant today.

What do you remember from the LA riots? How does that time influence LA today?

I just turned eight a few weeks before the riots began in 1992, and I grew up in the suburbs, removed from the immediate action of the riots. I remember watching the burning on TV and struggling with seeing people who looked like me on the screen in obvious pain, anger, and frustration, but not quite understanding why. My parents did their damnedest to maintain our innocence, which is such a hard thing to do in a world that doesn’t allow Black children to stay children for long. For the rest of that school year, whenever people got into arguments on the playground it became a running joke to yell, “Can’t we all just get along?” There’s something both so innocent and complicated and heartbreaking about that to me now.

Los Angeles still hasn’t fully recovered from the riots. There are swathes of South Los Angeles that still very much bear the scars of 1992. Empty lots that have stayed that way for decades. Business that left the area and never returned. After the riots, there was an exodus of Black people out of Los Angeles and the very demographics of the city are impacted by the riots. South LA has been especially ripe for the forces of gentrification because of years of neglect and a lack of economic resources poured into it both pre- and post-riots.

Who is your ideal reader for this book?

Everyone. I think Ashley’s story is very specific but also very universal. I hope that Black girls who had and are having upbringings closer to mine see their experiences reflected in its pages. I hope that Angelenos see something far closer to the city they know and love than how it’s usually represented. I hope that people who remember the pains and triumphs of growing up see themselves in its pages. And I hope that both younger and older people who might be looking for a way to understand how we find ourselves in this current moment might be able to reflect on Ashley’s journey as it relates to our ongoing cultural conversation on bias, systemic and institutional racism, and unequal policing.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!