Zetta Elliott Discusses the "Difficult Miracle" of Black Girl Poets

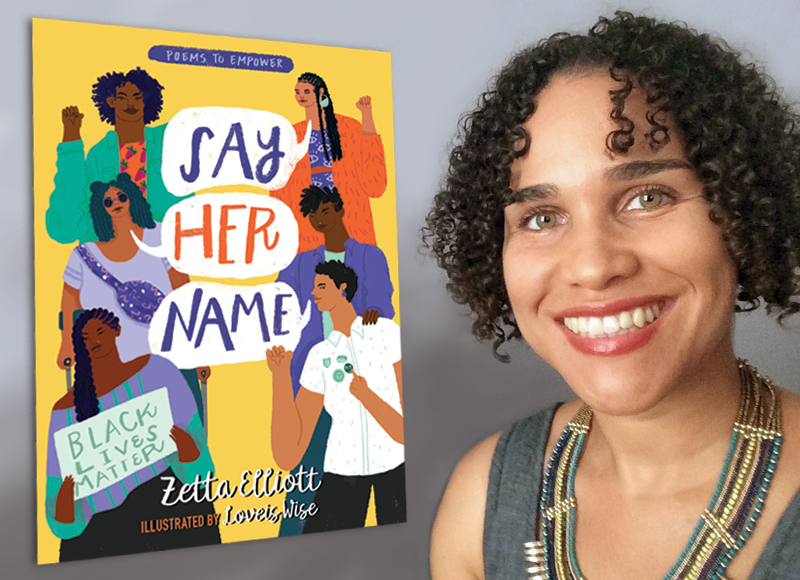

Award-winning author, scholar, and activist Zetta Elliott (Say Her Name) explains the importance of representation, not just diversity, in literature, as well as the incredible contributions of Black women writers.

Cover Art: Loveis Wise

Zetta Elliot, author of the poetry collection Say Her Name (Little, Brown/Jump at the Sun; Gr 7-10), writes about the inspiration behind her work and how the literary contributions of Black women poets and writers are often overlooked.

When I was in the eighth grade, Mr. Brown called me out of class. I didn’t know why the vice principal wanted me, but with mild dread, I joined the small group of students he had assembled in the hallway. Mr. Brown led us up to the library and for close to an hour we read and discussed the poetry of Robert Frost.

I wasn’t impressed. I liked poetry but I didn’t appreciate being pulled out of class without my consent for that kind of “enrichment.” Mr. Brown clearly felt he was doing me a favor because he commented on my “bad attitude” when I refused to express sufficient gratitude for the educational opportunity he was providing.

I was 12 at the time and already understood that being one of five Black students at my predominantly white suburban school carried certain risks. For four years I had struggled to earn the respect of my teachers. I skipped a grade when I was six and had always been recognized as academically advanced.

But when my parents divorced in 1981 and we moved to a new neighborhood on the outskirts of Toronto, I wasn’t placed in the “gifted and talented” program. I had to remain at my desk while select classmates were bused to a nearby school for activities that I knew I deserved, too. It was frustrating and unfair, but I felt powerless. The message was very clear—in the eyes of my new teacher, those kids were special. I was not.

In high school, I didn’t have to work as hard to prove my academic ability because my older sister had blazed a trail for me. Karyn had skipped a grade as well and always ended the school year on the honor roll and with an armful of awards. She wasn’t athletic like me and I wasn’t as pretty or popular as her, but she was a tough act to follow. I wasn’t about to disappoint my teachers’ expectations of excellence.

When I found myself in the class of an English teacher who had given my sister the astonishing grade of 99, I fully expected she would call me by her name. But unlike some other teachers, Ms. Vichert had no trouble distinguishing me from my accomplished older sister. I earned a perfect grade in her class and at the end of the year, Ms. Vichert took me aside to tell me I had a future as a writer.

I just mailed Ms. Vichert a copy of my first poetry collection, Say Her Name. We’ve kept in touch over the years and I try to mention her name as often as I can because, without her encouragement, I might not be a writer today. I only had one Black educator in my Canadian academic career, and the letter of support written by Professor Gerry Tucker helped earn me admission to a doctoral program at NYU.

In his class, I was introduced to the novels of Jamaica Kincaid, but I didn’t discover Black women poets until after I had graduated from college and moved to the U.S. I left Canada so I could finally study Black literature with Black professors and Black peers. I earned my PhD so that I could teach others about the incredible contributions of Black women writers.

Becoming a scholar and poet is something of a miracle; I had to overcome rocky beginnings in Canada and faced a decade of rejection trying to have my work published in the U.S. Of course, struggling to be seen, heard, and valued is an experience that links me to generations of Black women writers.

Poet June Jordan has examined the extraordinary life of Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved African child who grew up to be the first African American poet to publish a book in the eighteenth century. Jordan asserts that Black poetry in America is “a difficult miracle” since a poet “is somebody free. A poet is someone at home.”

Jordan marvels at the achievements of Phillis, an enslaved teenager: “After the flogging the lynch rope the general terror and weariness what should you know of a lyrical life? How could you, belonging to no one, but property to those despising the smiles of your soul, how could you dare to create yourself: a poet?”

Given all the obstacles placed in the path of African Americans for centuries, Jordan then asks, “How should there be Black poets in America?” Wheatley had to prove her mastery of neo-classical verse; today, Black writers who dare to reject literary conventions established by the dominant group are diminished by critics or dismissed outright. Yet Jordan concludes: “we persist, published or not, and loved or unloved: we persist.”

Say Her Name is my 36th book for young readers. I had to self-publish over 20 of my titles, including a workbook, Find Your Voice, which I developed to help teens write their own poetry. When I sit down to write, I always have my child-self in mind; I write the books I wish I could have read when I was 8, or 10, or 12. Who might I be today if I had had the books I needed back then? What if Mr. Brown had pulled me out of class to discuss the poetry of Lucille Clifton instead of Robert Frost? Would I have realized sooner that a poet’s life was possible for me?

There are four “mentor texts” in Say Her Name, poems written by Black women in previous eras that have nourished my imagination and provided a template for my own writing. In “won’t you celebrate with me,” Clifton writes about the dearth of role models for women of color: “…i had no model. / born in babylon / both nonwhite and woman / what did i see to be except myself?” Yet the speaker finds strength within and despite the daily threats facing Black women, ends the poem triumphantly: “…come celebrate / with me that everyday / something has tried to kill me / and has failed.”

Clifton’s words might serve as a balm for African American teens whose mental health is compromised by the racism they encounter on a daily basis. A recent study published by the Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology found that teens between the ages of 13 and 17 “experienced an average of five incidents of discrimination a day,” which (not surprisingly) led to an increase in depressive symptoms.

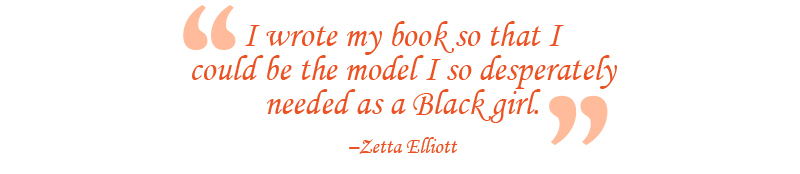

I wrote my book so that I could be the model I so desperately needed as a Black girl. I also hoped to embody possibility and challenge the invisibility imposed on today’s young Black readers. Two years ago, when the Brooklyn Public Library asked me to teach a series of workshops on Gwendolyn Brooks, I was dismayed to find that the teens in my class hadn’t even heard of the first African American to win the Pulitzer Prize. I introduced my students to some other Black women poets (Phillis Wheatley, Nikki Giovanni, Claudia Rankine) and realized I could reach even more young readers by publishing a book of poetry that included some of my literary sheroes.

Audre Lorde is another mentor included in the book, though I discovered her essays long before I read her poetry. In “Age, Race, Class and Sex: Women Redefining Difference,” a paper later reproduced in Sister Outsider, Lorde argues that “poetry has been the major voice of poor, working class, and Colored women. A room of one's own may be a necessity for writing prose, but so are reams of paper, a typewriter, and plenty of time.”

For women—and teens—with limited resources, “poetry is the most economical. It is the one which is the most secret, which requires the least physical labor, the least material, and the one which can be done between shifts…on the subway, and on scraps of surplus paper.”

It’s no surprise, then, that poetry is prized by young people needing a quick, inexpensive, and low-tech way to document their lives. Social media also provides new opportunities to share poems; teens can follow poets who post their work online instead of (or before) publishing traditionally.

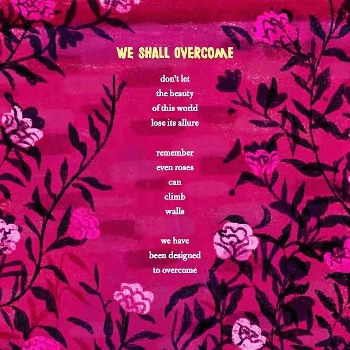

Illustrated by Loveis Wise

A few years ago, I couldn’t have imagined posting my own poetry on Instagram, but recently I shared “we shall overcome” on Martin Luther King Jr. Day. I’m not sure I would have posted the poem had Loveis Wise not cloaked it in such sumptuous color. Their vibrant illustrations illuminate the poems in Say Her Name, leavening some grim topics with beauty and whimsy. When people ask me what the book is about, I tell them it’s “#BlackLivesMatter meets #BlackGirlMagic” but reviewers have rightly noted that Say Her Name is a love letter—to my foremothers, my sisters, and the next generation of poets who will use their voices to change the world.

Zetta Elliott is an award-winning author, scholar, and activist. Born in Canada, she moved to the U.S. in 1994 to pursue her PhD in American Studies at NYU. She taught Black Studies at the college level for close to a decade and has worked with urban youth for thirty years. Her poetry has been published in New Daughters of Africa; We Rise, We Resist, We Raise Our Voices; the Cave Canem anthology The Ringing Ear: Black Poets Lean South; Check the Rhyme: an Anthology of Female Poets and Emcees; and Coloring Book: an Eclectic Anthology of Fiction and Poetry by Multicultural Writers. She is the author of over thirty books for young readers and currently lives in West Philadelphia. Visit zettaelliott.com to learn more.

Zetta Elliott is an award-winning author, scholar, and activist. Born in Canada, she moved to the U.S. in 1994 to pursue her PhD in American Studies at NYU. She taught Black Studies at the college level for close to a decade and has worked with urban youth for thirty years. Her poetry has been published in New Daughters of Africa; We Rise, We Resist, We Raise Our Voices; the Cave Canem anthology The Ringing Ear: Black Poets Lean South; Check the Rhyme: an Anthology of Female Poets and Emcees; and Coloring Book: an Eclectic Anthology of Fiction and Poetry by Multicultural Writers. She is the author of over thirty books for young readers and currently lives in West Philadelphia. Visit zettaelliott.com to learn more.

Read our review of Say Her Name.

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Gwendolyn Hooks

I don't read a lot of poetry although I love hearing it read aloud. I love to listen to NPR when their guests are poets, like Tracy K. Smith and Rita Dove. Your story is touching and I read it when I should be writing. Instead of moping around, I'm back at my desk. Ready to begin again. Can't wait to read SAY HER NAME!

Posted : Mar 09, 2020 09:04