It's Time To Go Mobile While Teaching News Literacy

News looks different depending on the device it's viewed on. Educators need to address that, say Jennifer LaGarde and Darren Hudgins in the first article in a series on news literacy.

In November 2019, The Pew Research Center released its findings related to the devices Americans use to access news. As in previous years, Pew found that news consumers overwhelmingly turn to their mobile devices, rather than to a laptop or desktop, to catch up on the news of the day. And yet, when we visit schools around the country to help teachers and librarians develop media literacy lessons, we find the exact opposite to be true. In school, the vast majority of news literacy instruction still takes place with the devices that our kids are least likely to use when they leave our buildings. This matters for a variety of reasons. Here are just a few:

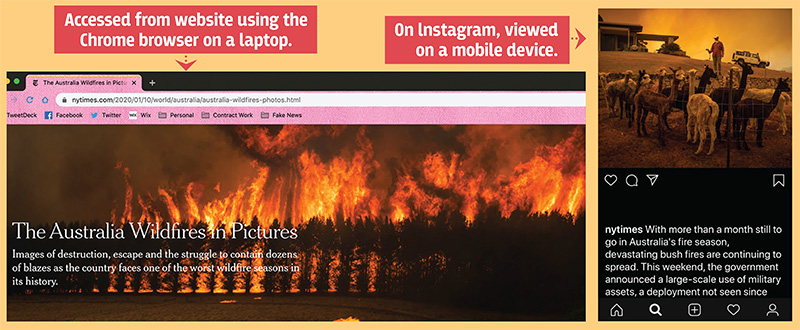

- The same news story looks vastly different when viewed on a mobile device versus a traditional browser.

- Similarly, the same news story varies greatly in appearance on two different apps. For example, while news stories on Instagram often require users to search the account's bio for links to additional information about the story, the same story in Snapchat might require readers to swipe up to read more.

- The ways in which students locate the information that is commonly required to determine credibility (author, date of publication, the editorial stance of the publication, etc.) also varies depending on the apps used to view the story.

- Commonly used protocols that require students to think about a URL’s domain (.edu vs .com, for example) don’t apply at all when viewing news through an app.

In short, the strategies being taught during school hours, to help young people determine fact from fiction in the information they consume, often do not transfer to the ways in which they access that information outside of school.

A story, for example, about 2020 brush fires in Australia, while (ultimately) from the same source, looks very different depending on the device (see below). If we agree that locating specific details about a story’s origin, and potential bias, are important steps in determining credibility, we must give our learners the tools for discovering that information on the platforms they are most likely to use during authentic inquiries.

|

Mobile devices (below right) create an environment that requires students to dig a bit deeper to locate basic information common in many credibility protocols. For example: Websites (below left) tend to provide more information about the source without having to click further.

|

Doing this doesn’t require tossing out exist pedagogical practices. Many educators employ a protocol, like the CRAAP test (see chart), as a way to encourage learners to look beyond the headline and dig more deeply into a story. To make these models even more effective, however, we have to give our students the opportunity to apply them in both web and mobile environments. Scaffolds like the one below can provide a mechanism through which learners can outline the steps for locating this critical information while also thinking deeply about how/why information looks different depending on the device.

|

Story/Source |

CRAAP TEST |

Web |

Mobile |

Reflection |

|

Students cite the story headline and source. |

C urrency R elevance A uthority A ccuracy P urpose |

Here students trace the path through which they locate the elements of the protocol while accessing the story on the web, listing specifically what they click on to determine when a story was published, etc. |

Here students go through the same process as with a web browser, but when using a mobile device. Optional: have students highlight differences. |

Here students reflect on which version of the story they felt was the most reliable and/or which version they found easier to dissect for credibility. |

|

Though from the same source, the headlines may vary between stories. |

All of that said, while there continues to be a socio-economic related gap in access to broadband Internet, with only 56 percent of low-income households having access, roughly 81 percent of all Americans own a smartphone. That means that even if your school doesn’t support carts of iPads, for example, chances are there are hundreds of personal mobile devices sitting in backpacks and lockers, just waiting to be tapped into.

But Cell Phones Are Banned At My School!

For a variety of reasons, some schools have policies prohibiting students from accessing their mobile devices during class time. There are a number of ways for you to work around phone rules and prepare students to be savvy digital detectives using these their own devices after the last bell rings.

Use your phone! Place your device under a document camera and then, once students have walked through the steps of the credibility protocol for the story on the web, do it together using your phone. You can ask students to tell you where to tap while you model the procedure.

Use your phone! Place your device under a document camera and then, once students have walked through the steps of the credibility protocol for the story on the web, do it together using your phone. You can ask students to tell you where to tap while you model the procedure.- Use donated devices. Lots of families have old phones lying in drawers collecting dust. It would only take a handful of these, connected to your school’s guest Wi-Fi, to enable learners to work in small groups to accomplish the same task.

- Go Analog. Whether you use the brush fire example or create your own, “screenshots” of news stories taken from mobile devices can be created to allow students to at least think about the places on the phone they might tap if they were using a real device.

- Talk to your admin. Use this lesson as an opportunity to chat with administrators about getting permission to lift the cell phone ban, in the library only, for the purpose of lessons on media/news literacy. If you come armed with information and passion for making a difference for kids, you might just find the flexibility you need.

Jennifer LaGarde and Darren Hudgins are co-authors of Fact VS Fiction: Teaching Critical Thinking In the Age of Fake News (ISTE 2018; #FactVSFiction). With more than 20 years in public education, LaGarde's educational passions include leveraging technology to help students develop authentic reading lives, meeting the needs of students living in poverty, and helping learners discern fact from fiction. Follow her at librarygirl.net or @jenniferlagarde. Hudgins (about.me/darren_hudgins) is the CEO of Think | Do | Thrive. He works with educators, school leaders, districts and school organizations to help build experiences that promote thought, play, and innovative strategies.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!