Teaching Black History Now

Across the country, educators, parents, and others keep Black history alive amid restrictions on how race is taught in schools.

|

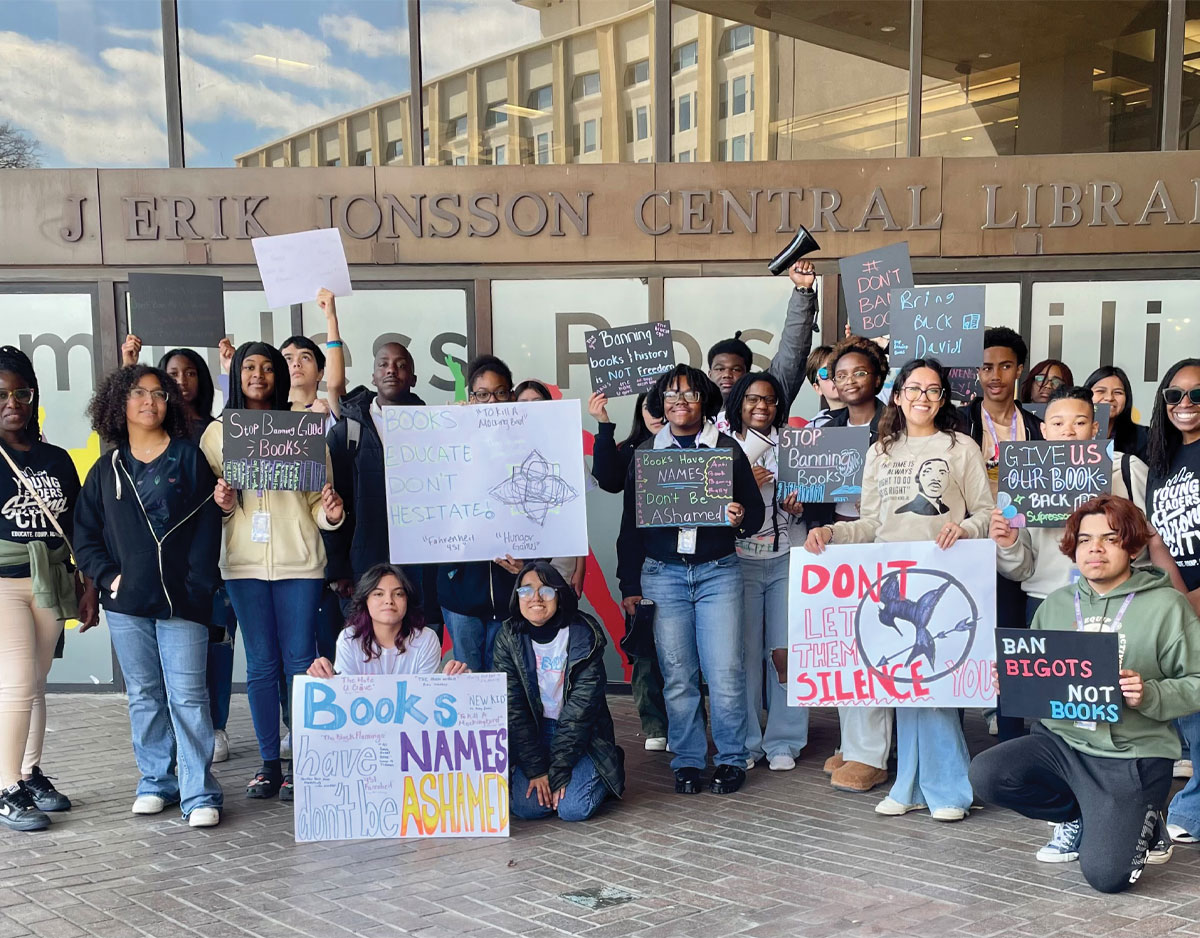

Da’Taeveyon Daniels (rear, with bullhorn) and members of Students Engaged in Advancing Texas, which spotlights student visibility in policymakingPhoto courtesy of Da’Taeveyon Daniels |

Across the United States, students sit in classes learning about significant events in American history, such as the Mayflower landing, the Great Depression, and beyond. But when it comes to lessons involving Black history, where a student resides could impact how much they are allowed to learn about the Middle Passage and enslavement, the Civil War and Reconstruction, the Tulsa Race Massacre, and more.

There’s a nationwide movement to restrict the teaching of topics involving race in schools. So far, at least 18 states have banned teaching critical race theory (CRT)—a decades-old academic framework that examines the intersection of race and the law and how policies perpetuate systemic racism—or have limited how race may be discussed in public schools. Three of those states have also denied inclusion of the College Board’s AP African American Studies course.

Despite the challenges, across the country—including in areas where the topic is carefully moderated by officials—educators, parents, students, and activists are finding ways to keep African American history alive during Black History Month and year-round.

“You can incorporate Black voices and stories into your lesson plans. You can use them as primary resources. You can have your guest speakers, intentionally seek out those community members that are leaders,” recommends Jean Darnell, a library advocate and blogger at “Awaken Librarian,” who recently relocated to Philadelphia from Texas. “My father worked at NASA. I was able to bring him in for our space and robotics program as an expert within the community and a Black male successful in science.”

Empowering student voices, Darnell adds, is another way to combat attempts at censorship in education.

“Giving voice to the voiceless is what a Black history program should center upon,” she says, adding that representation in class project displays and morning announcements is a small but helpful way to tell stories. “Have some QR codes that connect [students] to content and researchable materials.”

[Also read: 25 Diverse Audiobooks for Kids and Teens]

Darnell understands the hurdles faced by educators and librarians from her time working in Texas. The state’s law cites certain texts or speeches related to Black history that are acceptable but then goes so far as to state that schools cannot teach lessons from the New York Times’s 1619 Project, which reframes the founding of America to start when enslaved people first arrived on its shores. The law also instructs educators not to give deference to any one side when exploring a topic.

Da’Taeveyon Daniels, a high school senior and activist in Fort Worth, TX, says these officials are doing a disservice to future generations of children.

“When the lessons of history are erased from curricula in any given setting, then we are essentially on a negative trajectory,” says Daniels, who is an advisory council member of the National Coalition Against Censorship and the deputy executive director of Students Engaged in Advancing Texas, an organization highlighting student visibility in policymaking. “[The] trajectory not only diminishes what happened in the actuality of the events and the things that transpired, but it kind of sets us on a trajectory where we’re heading back towards those types of times.”

He adds, “When we essentially tell these students this history isn’t important and we tell this to future generations, we’re reestablishing those systemic barriers that existed so long ago.”

In addition to Texas, Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, Montana, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia have all put restrictions in place over the past few years.

In Iowa, the law bans teaching that the U.S. or state of Iowa is “fundamentally or systemically racist or sexist.” Kentucky, like Texas, mandates certain primary source documents be used in its social studies curriculum, which includes speeches and documents related to slavery and the civil rights movement. The bill, which was initially vetoed by Gov. Andy Beshear for trying to police classroom discussions on race, also notes that public schools teach that “regardless of one’s circumstances, an American has the ability to succeed when he or she is given sufficient opportunity and is committed to seizing that opportunity through hard work, pursuit of education, and good citizenship.”

|

The Spady Cultural Heritage Museum in Delray Beach, FL, hosts Saturday morning events for kids to learn about Black history.Michelle Brown, Spady Cultural Heritage Museum, 2024 |

Resistance gains momentum

Organizers, teachers unions, and parents across the country are pushing back against efforts to suppress the teaching of some aspects of Black history.

In Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Kansas, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Michigan, New Mexico, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, and Wyoming, anti-CRT bills have been vetoed, overturned, or stalled in the legislative process.

The Virginia Education Association encouraged its teachers to use alternative resources to counter Gov. Glenn Youngkin’s Executive Order 1 banning the teaching of what he called “inherently divisive concepts, like critical race theory, and its progeny.” According to the order, those lessons “instruct students to only view life through the lens of race and presumes that some students are consciously or unconsciously racist, sexist, or oppressive, and that other students are victims.” Meanwhile, in May, a federal judge overturned New Hampshire’s 2021 law that banned the teaching of “divisive concepts,” arguing the law was too vague for teachers to follow.

Even in Florida, which has paved the way for many of the bans, families are finding ways to ensure all aspects of Black history are taught by seeking lessons outside of school hours. It’s a pivotal movement. African American history has been a requirement in Florida schools since 1994, but provisions of the state’s new Individual Freedom Act, dubbed the Stop WOKE Act, require that “a person should not be instructed that he or she must feel guilt, anguish, or other forms of psychological distress for actions, in which he or she played no part.” The bill, championed by Gov. Ron DeSantis, also prohibits educators from critiquing concepts such as color blindness or discussing whether particular races or sexes inherently have certain privileges or disadvantages.

Even though the DeSantis bill allows that students be taught about slavery, racial segregation, oppression, and the civil rights movement, the politically charged rhetoric surrounding the bill’s implementation and the fear it caused among educators have many families concerned their children will receive a limited or censored version of the topics.

In response, some students are spending Saturday mornings learning about African American history at the Spady Cultural Heritage Museum in Delray Beach. There are similar programs at community centers across the state run by Black churches and other organizations.

Christopher Stewart, senior librarian at Columbia Heights Education Campus in Washington, DC, says he hopes to see more free or virtual after-school opportunities develop in response to the growing restrictions across the country.

“Hopefully this is an opportunity that inspires and empowers not only the younger generation, but their parents and grandparents to possibly run for office,” says Stewart, who also teaches at St. John’s and Syracuse universities. “If you see that something is not right, it’s not ethical, not moral, not just, then you change it by doing the hard work, becoming the hard work, which means essentially running for office and not electing individuals who are making such rules and policies that are centered in hate, to put it bluntly.”

Florida’s law has also had an impact at the collegiate level because state funds cannot be used for diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Lauren Odom, an instruction librarian at the University of North Florida, says they could not label one of their displays with a “Black History Month” sign.

“We could no longer advertise it as that,” she says.

Odom sees librarians as the gatekeepers of knowledge, so these restrictive rules are contrary to their mission.

“It is our job to make sure that information is accessible,” she says. “Not only is it accessible in choosing collections and purchasing certain books from vendors to make sure that they’re part of a collection. But also showing people how to go about getting access to the tools that are available that they may not know about. And so in the limitation and having mandates like this, it limits how much we can provide access.”

Requirement doesn’t mean implementation

In contrast to the bans, 12 states have mandates that require Black history be taught in public schools: Arkansas, Colorado, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Washington. In addition, the city of Philadelphia (but not all of Pennsylvania) has required that every high schooler take African American history to graduate since 2005.

But not all mandates are alike. Sundjata Sekou, a third grade teacher at Mt. Vernon Avenue Elementary School in Irvington, NJ, says he’s just as disheartened with New Jersey’s law as he is with the one in Florida.

Both states mandate the teaching of Black history, but implementation isn’t consistent in either state. New Jersey’s Amistad Bill, signed into law in 2002 and hailed as progressive at the time, created a commission whose goal was to ensure the history of Africans and African Americans be infused into the state education curriculum. But progress stalled. To date, no such widespread curriculum exists. Instead, individual schools or districts are left to chart their own path.

“Florida and New Jersey are symbiotic in the way of not implementing Black history at all,” says Sekou, who is on sabbatical from teaching this year and is the 2024 writer in residence for the National Education Association. “You have individual teachers I like to call abolitionist educators who bring it into the classroom, but a systematic approach to Black history that’s not only in February—it’s been done nowhere in New Jersey.”

|

Jean Darnell leads a library event for young children.Courtesy of Jean Darnell |

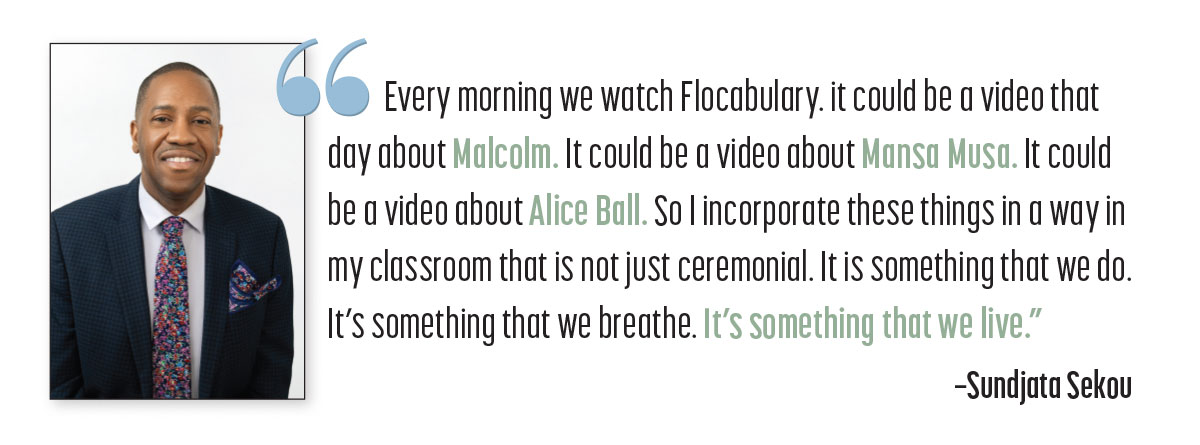

Still, Sekou praised his fellow educators, many of whom, he says, are doing wonderful things in the classroom. At his school, he did his part as well.

“Every morning for breakfast, we watch Flocabulary [a learning program with educational hip-hop music videos]. And on Flocabulary, it could be a video that day about Malcolm. It could be a video about Mansa Musa. It could be a video about Alice Ball,” he says. “So I incorporate these things in a way in my classroom that it’s not just ceremonial. It is something that we do. It’s something that we breathe. It’s something that we live. One year, my class rules were the Kwanzaa principles. ‘Kujichagulia, clap it out.’ Those things are systematic in the classroom, my classroom.”

As a math and science teacher, Sekou says he had his elementary students study and present about Black scientists and mathematicians and their research.

“One of my greatest times teaching was when we were having a conversation in the morning about the school breakfast program,” he says. “A couple of months in, I was like, ‘You guys know who started this school breakfast program?’ And one of the students raises his hand: ‘Mr. Sekou told us. It was the Black Panther Party.’ So these are the little nuggets I try to impart to [students].”

The District of Columbia updated its social studies curriculum with changes that are more inclusive and take a closer look at racism and white supremacy. It was the first update in 17 years. Stewart says it’s an important step because there were so many missed opportunities to explore.

“We want to ensure every student and teacher can have a more robust understanding of African American history in the U.S.,” he says.

He also suggested that educators and librarians work with their community partners, and center Black joy and creativity in their lessons. For instance, this month he’ll be showcasing Black art and artists, such as Faith Ringgold, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Jacob Lawrence, Romare Bearden, and Alma Thomas, in the library. He also plans to explore Black wealth with his students.

“We often hear the narrative of those who are experiencing poverty, living below the poverty line. But we don’t hear this idea of Blacks who are able to create and amass wealth and serve their communities well,” he says. “[We should] not just simply shout out to all the entertainers and basketball stars and football and music and all that. It’s great...but it’s more than that. It’s our collections, it’s philanthropy.”

Stewart also plans to take a group of young men in March to Alabama to visit Selma, Montgomery, and Birmingham on a school trip. It’ll give them an opportunity to hear firsthand accounts from people involved in the civil rights movement that they’ve read about.

He says these are the ways to expand learning beyond the classroom or bring to life lessons from the new AP African American Studies course, which was piloted last year, including at Bell Multicultural High School, where he works.

States at odds on AP course

In Florida, DeSantis has blocked students from gaining access to the AP course, claiming it lacks educational value. Arkansas and South Carolina have also restricted teaching of the new course in its state high schools. South Carolina school officials cited the controversy surrounding the course and pending state legislation on the topic, but say local districts could offer the course for honors (not college) credit.

Georgia state schools superintendent Richard Woods reversed a decision to prevent schools from teaching the AP course after backlash from the state educators’ association and parents. Woods also says that he was concerned the course violated the state’s law, which prohibits teaching divisive racial concepts. But the state attorney general ruled that such college-level courses were exempt from the law. Still, Woods’s decision allows districts to pick and choose portions of the curriculum, which could allow for censorship, critics argue.

In Virginia, Youngkin also ordered a review of the class to see if it violated his executive order, but the course was approved by the state’s education department months later.

Daniels, who plans to attend Rice University in Houston in the fall, says it’s ironic that AP world history is taught in schools with little fanfare, but African American history causes an uproar.

“We allow kids to take part in AP world history and explore the atrocities of the world wars and so many other horrible instances in history. And we kind of preface that conversation by saying this is something that the world lived through, so we need to learn from it and become stronger and more united as one,” he says. “But it’s a different scenario when it comes to Black history, specifically when we talk about slavery in America and that detrimental impact, but also the crucial part that slavery had in building America into what it is today. So I feel like it’s a bit of an ironic take to tell students this is to protect students from being sad. I just feel like that’s a disingenuous approach.”

|

From the left: A community member speaks at a Douglas County (CO) Board of Education meeting in December 2024;the BOE directors who approved teaching AP African American Studies after objection from some members of the public.Screenshots from Douglas County Board of Education meeting |

Other school districts, such as Douglas County in Colorado, recently approved the course even after questions were raised by some members of the public. Directors on the seven-member Board of Education (BOE) spent weeks reviewing the curriculum and received hundreds of emails from parents and students supporting the course, as well as endorsements from district educators, before ultimately making their unanimous decision.

“I do believe in the importance of providing students with a comprehensive and inclusive education that reflects the diversity of our shared history. And like we heard tonight, this curriculum offers academically rigorous and well-rounded exploration of African American history, culture and contributions to society,” BOE member Valerie Thompson said at the meeting. “Our full board supporting this course will demonstrate our dedication to academic equity, educational innovation, and the preparation of our students as informed and engaged citizens.”

In his remarks supporting the decision to approve the course, BOE member Brad Geiger said it was important “to give students a fair opportunity to formulate their own decisions about what happened in the past and how that impacts the current and the future, and I trust our teachers to fairly guide them.”

“This is about choice,” he added. “This is about saying that if you want your kid to learn hard things, we will give you that opportunity.”

Sekou says classes such as the AP course allow educators to teach the whole story and help students make connections to present-day events.

“There’s context. There’s history,” he says.

For instance, a discussion about the family separation policy of undocumented migrants in America can connect to slavery.

“People in this country have had separation of families since its inception. The mother would have the child and the child would be sold,” he says. “You had Black people that couldn’t move certain places without showing their documents, showing that they’re free.”

“So, if you want to know about the American story,” Sekou adds, “you cannot tell the American story without the Black freedom struggle.”

Daniels applauds districts that are allowing the AP course and those mandating that Black history be taught—authentically—in classrooms without censorship.

“Black history is American history. Black history is international history,” he says. “It’s very critical to a well-rounded education.”

Christina Joseph is an editor, writer, and content strategist with expertise in race relations, immigration, education, health care, and government.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!