Robin Benway Opens Up About Her National Book Award–Winning YA Novel

Benway received her National Book Award in New York City on November 15.

Photo by Beowulf Sheehan, courtesy of NBF

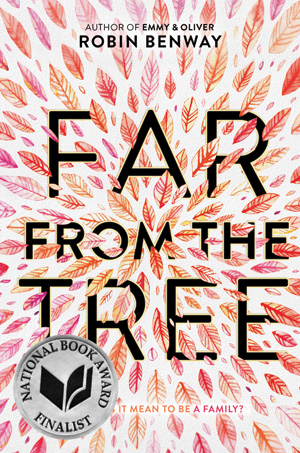

Young adult author Robin Benway was helping her mother move into a new condo when she got the news that she had made the National Book Award long list. Benway, a six-time author, a Los Angeles native, and a graduate of UCLA, says her extensive research for the award-winning Far from the Tree (HarperCollins) was “a daily eye-opener in good and bad ways.” It went on to win the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature on November 15.

Sarah Hannah Gómez: What is your connection to adoption? Robin Benway: I don’t really have a connection with adoption. No one in my immediate family is adopted or has adopted. I spent eight months researching and looking at all the different aspects of adoption, and talking to many different people. I talked to adoption attorneys, families who privately adopted, and social workers. I talked to adoption liaisons, someone who worked with a birth mother, and an adoptive family. And I read a ton of books about adoption, just trying to make sure that I understood what I was taking on, because I just didn’t want to get it wrong. I really wanted to be careful in what I was doing.

What made you want to write about it? I had been working on a book idea for a very long time, and it just wasn’t working out. And of course my deadlines were whizzing past me at HarperCollins. I finally emailed my editor and [said], “I need to take a break. I don’t have any ideas for you, and as soon as I have one, I’ll let you know.”

Then a week later, I heard a Florence + The Machine song. I was in the parking lot at a Costco on Fourth of July weekend. I heard, “A falling star fell from your heart and landed in my eyes,” and immediately [thought]: Oh my gosh, this book is about adoption. It just made me think about a birth mother giving her baby up for adoption, and maybe that baby, without even realizing it, was carrying some part of that mother and that mother’s love with them.

In the car I wrote an email to my editor and talked it out, and she immediately wrote back. That’s the book I ended up writing. It just took a long time to figure out how to tell that story. But I knew the three siblings right away. It was this divine intervention, I guess.

I was adopted, so I’m always wary when I see an adoption story. But one of the things I really loved about this was your inclusion of four different kinds of adoption experiences. And each one’s different, but they all feel really accurate and authentic. Which one of those experiences, if any, did you find the easiest to understand and explore? I started from Grace, because I knew I wanted her chapter [to be about] having Peach. I knew that wanted to be the opening chapter. I wanted that from page two—this girl’s going to have a baby.

I was adopted, so I’m always wary when I see an adoption story. But one of the things I really loved about this was your inclusion of four different kinds of adoption experiences. And each one’s different, but they all feel really accurate and authentic. Which one of those experiences, if any, did you find the easiest to understand and explore? I started from Grace, because I knew I wanted her chapter [to be about] having Peach. I knew that wanted to be the opening chapter. I wanted that from page two—this girl’s going to have a baby.

Grace’s was the easiest, because she’s in so much pain. But out of all three siblings, she’s had the most support her whole life.

Maya’s parents love her so much and they’re so supportive of her, but they’re falling apart. And that foundation for her is crumbling. Joaquin is in a great place with his foster parents, but he’s been burned, and he doesn’t always trust. Grace has a strong foundation, so I felt like she was in the safest place out of all three siblings.

I spent months agonizing: Am I the one to tell this story, with no experience? Is it OK to tell this story? And then doing it correctly. I finally decided, I can tell only three people’s stories—Grace and Maya and Joaquin. And not everyone who is adopted or in foster care will be able to relate to their stories, and that’s really OK. I just didn’t want to cast a net so wide that their stories didn’t feel real.

Another thing you engage with in this book is race and ethnicity, particularly how Joaquin sees himself separate from his sisters because of his foster care status but also because he’s half Mexican and they’re white. How did you conceptualize and work through that? When I was doing all the initial research about adoption, I came across an NPR story that talked about how in private adoption, white girls cost a lot more to adopt. The adoption fees were a lot higher.

I’m not naïve; I know why. But at the same time, to see it in a financial number was very disturbing. I started doing a lot of research, and [I discovered that] the rate of kids of color who are taken out of their parents’ homes and put into foster care is a lot higher than white kids. [Boys] who are left in foster care who grow up—they’re 12 and 13 and 14—they start to look like men. They go through puberty, and people don’t want to adopt men. They want babies.

That’s obviously a generalized statement. Not everyone feels that way. But as I started to do this research I realized that I have to tell another aspect of the story. Not everybody can afford to pay $70,000 to adopt a child.... I just thought, I want to talk about that in the book.

And as a white woman I was very nervous about talking about that. So I talked to a lot of my friends who are biracial to get their opinions. A friend of mine is a professor of Chicano studies at Cal State Northridge in L.A., and I had a lot of meetings and conversations with her. She was really helpful. I just wanted to explore it as sensitively as possible but at the same time shine a light on it as well. I tried very, very hard to make sure that Joaquin was represented as accurately as possible.

Robin Benway and her dog Hudson.

Photo courtesy of Robin Benway

I found myself in Grace because Grace wants to find her birth mom. You would think she would be the most resentful one, not Maya. But I think it’s because she’s the most satisfied with adoption and thinks, “Wouldn’t this be a cool thing to learn?” even though there’s nothing missing from her life. You know, I think Grace doesn’t want to connect to her biological mom as a daughter. She wants to connect to her as a mother, because she has that connection. She needs someone who maybe would recognize that pain that she feels. Before [she was pregnant], Grace had no interest in connecting with her, and then afterward connects to her on a very different level.

I love that you thank Grace, Joaquin, and Maya at the end of your acknowledgments. After I won the award, one of my first thoughts was, “Oh, I want to tell them.” I can’t, they’re not real, but—I don’t know, they feel so real to me. I spent so much time with them, and I put them through so much that I wish in some weird way they could experience that good stuff.

So the question that every interviewer has to ask, even though everybody hates answering it: What are you working on? I am not working on a thing right now. I honestly am not. Far from the Tree was really emotional, and I just needed to step back and recharge my batteries. I was long-listed three weeks before the book came out, short-listed the day after the book came out. There’s just been so much going on, and travel, and so much energy and anxiety and thrills. I’m just going to enjoy this.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!