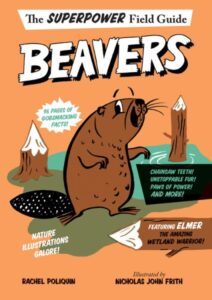

Review of the Day: Beavers – The Superpower Field Guide by Rachel Poliquin and Nicholas John Frith

Beavers: The Superpower Field Guide

Beavers: The Superpower Field Guide

By Rachel Poliquin

Illustrated by Nicholas John Frith

$18.99

ISBN: 9780544949874

Ages 9-12

On shelves December 4th

Here, sit down a sec. I wanna tell you a story about this beaver I once knew. So I’m at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago, which, if anyone asks, is my favorite zoo. I know it’s not as big and impressive as some of the others out there, but its doable, right? First off, it’s free and then if you want to you can see all kinds of great animals in a short amount of time in a walkable space. What’s not to love? I’m with my kids and we’re going through the exhibits, and we come to a building where you have a clear view of an area that’s both above and below the water. And frolicking (I have to say frolicking because there honestly was no other way to describe it) is a beaver. A big, incredibly happy, to judge by its actions, beaver. With movements so lithe and liquid, we immediately assumed it was some kind of gargantuan otter, but there’s no mistaking that tail and those teeth. And to be perfectly honest, as I watched it cavort with a grace that belied its bulky bod, I had to sit down and come to grips with the fact that I don’t know a heck of a lot about beavers, aside from the ones in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe. If pressed I could have told you that they build dams and chop down trees with their teeth. But is there any particular reason to know more than that? Turns out, that happy beaver dude was just the tip of the proverbial iceberg. So says the first book in the Superhero Field Guide series, Beavers, which turns out to be the most inventive, fun, and downright delightful science title I’ve had the pleasure to read in a long time. Beavers! Who knew?

Have you ever watched an episode of Wild Kratts on PBS? It’s a show that talks about the “amazing creature powers” of animals in the wild. Well, in the Superpower Field Guide series, the books do very much the same thing, but for an older audience a.k.a. those kids that may have watched the Wild Kratts show when they were younger and outgrew it but still love wildlife. And what better animal to begin with than the beaver? This seemingly innocuous animal is chock full of fascinating aspects and qualities. Some of these you may be familiar with. They see underwater so well, and you knew that, but were you aware it was because they actually had a transparent eyelid (or nictitating membrane) to protect their eyes? Built in goggles? And you probably knew that they gnaw on trees to bring them down, but were you aware that beavers actually eat parts of those trees while they gnaw? Multitasking! Consistently throughout this book, Rachel Poliquin pulls a seemingly endless string of fascinating facts about the beaver out of her hat. For example, why did Europe go crazy for beaver hats in the past? Because the waterproof skins never loose their shape (think Pilgrim hats or Napoleon’s hat and suddenly everything falls into place). Accompanying Poliquin’s words are Nicholas John Frith’s peppy pictures, which give the entire enterprise a retro 50s look and feel. As enjoyable to read as it is to view, this book will make a beaver convert out of any kid reader. Gnaw doubt about it

(I am . . . SO sorry for that).

What sort of kills me with this book is that I’ve already Rodney Dangerfielded it. Which is to say, I’m working on the assumption that it isn’t going to get enough respect. Though Frith’s art and the design of the cover were enough to lure me into a deep read, what about the kids that aren’t majorly into animals? Look at it another way. What kinds of nonfiction win big children’s literature awards? The bulk (not all, but the bulk) goes to biographies. People. People make for good stories. I’m a person. You’re a person. We relate to people better than critters, and this book is set squarely in critter territory. And yet, one of the many marks of great writing is an ability to engage the reader and make them feel passionate about the material, regardless of its content. Whether you’re writing about toads or toadstools, the book needs to have some kind of pull. That’s where Poliquin shines. It isn’t enough that the material has interesting facts. It’s how she lays them out, how she binds them to the swell and flow of the story, and how she honest-to-goodness finds a way to build to a crescendo. The great secret of Beavers is that it ends on a high note. You learn, by the end of the book, the world’s craziest fact about beavers and how they prepare for winter. I don’t want to spoil it so I won’t say anything more, but you’re going to read this book and then afterwards find yourself accosting strangers on the street saying, “DO YOU KNOW WHAT BEAVERS DO IN THE WINTER? DO YOU?!?” Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

You don’t believe me. I can’t blame you. It seems odd. So at the risk of ruining some of the surprise of the book, I’m going to let you in on a couple beaver facts. At this point my respect for Poliquin’s writing is such that I honestly believe she could make the common fruit fly interesting, but her subject in this particular case really is remarkable. Here, I’ll give you one of the most interesting beaver facts here as a final example (don’t want to give away too much). Consider a beaver dam. The beaver has taken down a lot of the surrounding trees, and because those trees were next to the water, it didn’t have to drag them very far. Now what if the beaver wants trees a little farther away? Will it just gnaw them down and then drag them over land? Nope. Instead, it will dig a trench from the lake or river where it lives to the desirable tree trunks. Once the canal is there it takes down the tree, drops it into the canal, and then pulls it in the water back to the dam. This is problem solving at its most genius. Sorry crows, gorillas, and polar bears. I’m thoroughly convinced that beavers will end up ruling us all.

You know why I like kids so much? They’re honest. Horribly, bluntly, frighteningly honest in their preferences. They say don’t judge a book by its cover but come on, man. We all do it. Adults just lie about it half the time. Not a kid. As a former children’s librarian I can attest to that glazed look a kid’s eyes get when you show them a book with an awful cover. They can be polite as they try to explain to you that this isn’t really their “kind of book”, but you know what they’re really saying. Heck, half the time I’d hide the book behind my back while booktalking it, just so they wouldn’t judge it too soon. No need to do that with Beavers, though. The idea to give it that kooky 50s game show spin on the art was inspired. Whoever thought to tap Nicholas John Frith to do the illustrations knew what they were on about. His thick black lines and relentless cheer gives the whole operation this fun and funny feel. But even better than that is the book’s design. We, as consumers, spend an insignificant speck of our gray matter considering the designers of the books we read, but frequently they’re the whole reason we pick up something because it “looks interesting”. Bad design can sink even the most thrilling topic, and good design? You’re looking at it in Beavers, baby. You know how adults are convinced that kids love infographics as much as they do? It’s a lie. Kids hate ‘em. What they love are books designed with a fun presentation of facts in mind. It’s just an added bonus that the writing’s good enough to match, honestly.

In spite of that beaver I spotted at the Lincoln Park Zoo, I didn’t really go all in on beavers until this book, and that’s the god’s own truth. Is it perfect? Is anything? I don’t even know what the standard rate of comparison would be at this point. Has there ever even been a truly extraordinary nonfiction book about beavers for kids between the ages of nine and twelve before? I mean, the very concept strikes you as silly, right? And yet here we are. This is a book that sets you up to want to know more about its subject matter, while at the same time satisfying any questions you didn’t know to ask. Beavers make for good books. Poliquin’s writing and Frith’s art do the subject matter justice. And child readers will, as one, become beaver enthusiasts (and possible nature conservationists as well) as a result. Yeah. I just wrote an incredibly long review about a beaver book. Better pick it up. If you do, you’ll understand.

On shelves December 4th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Misc: You won’t find any of these images in this book, but if you want to see some great beaver-related primary documents, author Rachel Poliquin has the goods on her website.

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!