School Librarians Poised To Support Student Success, Information Literacy Survey Shows

Evaluating sources and using information effectively is critical. The right tools and support can help librarians teach these skills better, according to SLJ’s survey of middle and high school librarians.

|

Illustrations by nadia_bormotova/Getty Images Plus |

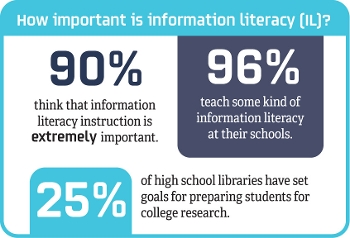

Information literacy for students is “extremely important,” say 90 percent of high school and middle school librarians in SLJ’s new survey on information literacy and college readiness. An even higher percentage—96 percent—confirm that information literacy is taught at their school.

While librarians feel strongly about the subject, they also cite challenges to effectively teaching it, including lack of administrative support and not enough time in their schedules. Only one-fourth of high school libraries have set goals for college readiness, according to high school librarians responding to the survey.

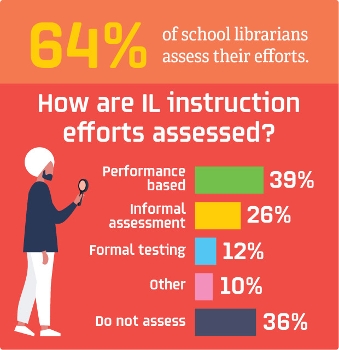

While almost all librarians surveyed highly value information literacy instruction, only 64 percent formally assess the effectiveness of their lessons. Most instruction occurs in ninth grade or earlier, the survey shows. To varying degrees, school librarians partner with teachers, each other, and public and academic librarians.

School librarians also have a lot to say about the perfect resources they’d like to have for this instruction. Here’s more about the survey and what librarians say they need to succeed.

The college readiness gap

The survey defined information literacy as research skills that let students discover and evaluate credible, valid resources and use information effectively and ethically through critical thinking. Why is there such a gap between knowing what needs to be taught, and accomplishing it? There are a host of reasons, school librarians say, ranging from lack of time with students, lack of faculty and administration support, and low budgets that hamper efforts to both staff libraries adequately and purchase proper resources.

The survey defined information literacy as research skills that let students discover and evaluate credible, valid resources and use information effectively and ethically through critical thinking. Why is there such a gap between knowing what needs to be taught, and accomplishing it? There are a host of reasons, school librarians say, ranging from lack of time with students, lack of faculty and administration support, and low budgets that hamper efforts to both staff libraries adequately and purchase proper resources.

“It is difficult for one librarian in a school of 700 students to offer comprehensive information literacy instruction,” wrote Carrie Day of Wasilla (AK) Middle School. “Even if teachers fully cooperated, there aren’t enough hours in the week to see all classes equally.”

Time is the biggest challenge, nearly 70 percent of librarians in the survey agreed. More than half of respondents report that they “actively engaged” in instruction with students once a month or less. In addition, 80 percent say they teamed with classroom teachers on this subject once a month or less.

“Content area teachers are so prescribed now with what they have to teach on which day and for how long, they often do not have time to allow even for a day or two for me to teach their students and integrate information literacy into their content,” wrote Jill Rodgers, library media specialist at Northgate (MO) Middle School.

“We used to have a very comprehensive seven-to-10-day orientation for freshmen that covered the range from identifying an information need to finally presenting it to others,” another respondent said. “It got cut back, due to a variety of issues, and now I have to cram it into two days.”

Cassy Lee finds time to stay actively engaged. “I don’t teach my own classes, but have collaborations throughout the year with teachers in all the grades (6–8) in many subjects,” wrote Lee, middle school learning center coordinator at the Chinese American International School in San Francisco, and SLJ’s 2018 Champion of Student Voice. “I co-plan research projects in which I embed info literacy lessons, provide resources, and suggest alternative assessments that are more plagiarism-proof than most teachers are used to assigning.”

Challenges start at the top

Responding high school librarians estimate that 69 percent of their 12th graders are college bound. So why have only a quarter of their schools set goals to prepare students for college research?

Responding high school librarians estimate that 69 percent of their 12th graders are college bound. So why have only a quarter of their schools set goals to prepare students for college research?

Digging deeper into their comments, two trends emerge. One, many say that their school administrators are not taking this issue seriously enough. That, combined with teachers’ time crunch, leads to educators giving the subject short shrift or not being trained to teach information literacy to high standards.

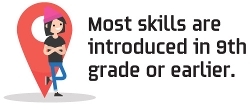

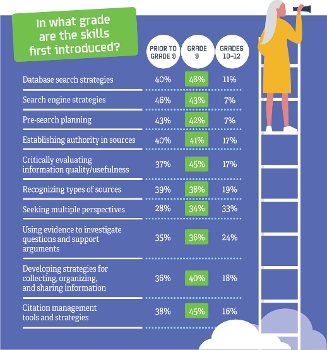

The survey also explored when students are first introduced to various topics. Nearly half of students aren’t taught how to critically evaluate information until ninth grade. Topic areas ranging from database search strategies to effectively using open web resources such as Google Scholar and Google News are most often introduced to students when they are high school freshmen.

The survey also explored when students are first introduced to various topics. Nearly half of students aren’t taught how to critically evaluate information until ninth grade. Topic areas ranging from database search strategies to effectively using open web resources such as Google Scholar and Google News are most often introduced to students when they are high school freshmen.

Fifty-nine percent of respondents in both middle and high schools say they lack faculty support, while 31 percent cite lack of administrative support. “Although I have great moral support for my library, information literacy instruction is not a priority for my administration,” wrote Betsy Kahn of South Pasadena (CA) Middle School. “There is a wide range [of] interest in it among teachers, from none to quite a bit. It makes it very hard to deliver a consistent program of instruction.”

“Teachers do not have the training or the time to teach these skills by themselves,” wrote Susan Rahkonen, librarian from the Mukilteo (WA) School District.

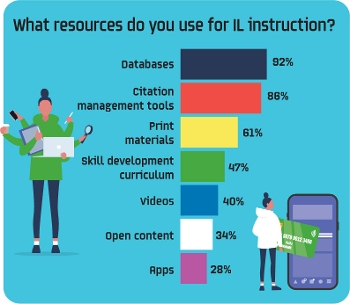

What teaching tools are librarians currently using? Most say they use databases, citation management tools, and print materials, with slightly less than half mentioning information literacy skill development curriculum.

The survey broke information literacy into 13 distinct skills. Almost half of the topics—from search engine strategies to information ethics including attribution and citation—are introduced by 40 percent of schools before high school. Seeking multiple perspectives and using open web services such as Google Scholar, were taught by about one in four middle/junior high schools. None was taught before high school by more than half the schools. Fifty-four percent of librarians introduced concepts from the ACRL framework, while others used AASL, ISTE, ALA, or state/provincial library standards.

Demographics, partnerships, and assessments

The survey showed some interesting patterns when parsing answers by region or an area’s metro status. Fewer than four in 10 rural school librarians reported teaching students daily or weekly in this topic, while nearly half of librarians in a small town or urban areas had at least weekly contact with students while teaching information literacy. Rural middle school students were also least likely to be taught how to evaluate information or use information responsibly when compared with students in urban, suburban, or small town areas.

The survey showed some interesting patterns when parsing answers by region or an area’s metro status. Fewer than four in 10 rural school librarians reported teaching students daily or weekly in this topic, while nearly half of librarians in a small town or urban areas had at least weekly contact with students while teaching information literacy. Rural middle school students were also least likely to be taught how to evaluate information or use information responsibly when compared with students in urban, suburban, or small town areas.

Looking at which high school libraries are likely to partner with public libraries, urban districts are at the top of the list with 30 percent creating partnerships. In the Midwest, only 12 percent of schools say they partner with public libraries.

More than half of high school librarians partner with middle schools to develop information literacy. Only 23 percent of high school librarians partner with post-secondary institutions to teach information literacy. Within those, most partnerships involve encouraging students to visit a college or university library (51 percent) or examining the academic library website with students (45 percent). Sixteen percent of respondents say they collaborate directly with academic libraries.

While 64 percent of librarians assess their information literacy instruction efforts, many rely on informal assessment methods such as observing students as they conduct their research. Thirty-nine percent use performance-based assessments, and 12 percent conduct formal testing.

Librarians describe their “perfect resources”

Despite challenges, librarians remain committed. “I provided professional development for staff and other librarians in the district on information literacy skills,” wrote Karin Ledford, teacher librarian at Elk Grove (CA) Unified School District. “I also teach this in collaboration with our English department and with some in our social science department.”

More than 85 answered the open-ended question about their information literacy wish list—what the perfect resource would be to teach it better.

Many asked for apps, web extensions, and websites to better tackle this complex subject. Kahn summed up the problem concisely, writing, “A completely vertically integrated K–12 curriculum that was consistently applied district-wide so I know what skills incoming sixth graders arrive with and can send eighth graders off to high school with what they need.”

Many asked for apps, web extensions, and websites to better tackle this complex subject. Kahn summed up the problem concisely, writing, “A completely vertically integrated K–12 curriculum that was consistently applied district-wide so I know what skills incoming sixth graders arrive with and can send eighth graders off to high school with what they need.”

An ideal resource “would include vocabulary essential to research skills, libraries, and information literacy. It would have fun, meaningful lessons/activities to orient middle-school aged students to information literacy. This could come in the form of both print and online/digital resources,” wrote Susan Pennington, a library media specialist in Springfield (IL) Public School District 1236.

Some respondents asked for video tutorials. Lee suggests “a curriculum including brief, engaging mini-lessons and short well-produced videos geared toward middle schoolers to embed throughout longer research projects to teach discrete sets of skills and concepts.”

A tool that is “adaptable, based in research, aligned to colleges nearby, [and provides] college credit for completion of coursework” is what TuesD Chambers, a high school librarian in the Seattle Public School District, would like to see. Amy Linden of California’s El Dorado Union High School District envisions “a leveled (by grade and skills) resource that agrees with AASL Standards that could be adopted by school districts as a curriculum set, K–12.” Linden added, “The key is to get districts to make that expenditure a priority.” For Anne Ernst, media specialist at Charlottesville (VA) High School, the ideal is “a constantly updated database or website.”

Respondents estimate they spend an average of $6,500 on digital resources to support information literacy education, although only 14 percent of librarians say they purchased or subscribed to any dedicated resources for this topic.

The bulk of this money, about 75 percent, comes from school library budgets, while about one in four respondents say funds come from their school or district’s technology budget.

Still, librarians were proud to point out their triumphs. One high school librarian in Maine wrote that because she was alone in her library, she frequently had to close the library to teach information literacy. She remained upbeat: “It is an ongoing challenge, which I am determined to win.”

Download SLJ's Information Literacy/College Readiness Survey Report |

METHODOLOGY: The Information Literacy/College Readiness Survey was developed by SLJ Research in conjunction with Credo Reference. A survey invitation was emailed to a selection of middle and high school libraries on April 26, 2019. The survey closed on May 14 with 443 responses. The data was tabulated and analyzed in-house by SLJ Research. The responses are unweighted.

Wayne D’Orio is a freelance journalist and a regular Hechinger Report contributor who writes frequently about education and equity.

Wayne D’Orio is a freelance journalist and a regular Hechinger Report contributor who writes frequently about education and equity.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!