These Musicians Rock American History

“What’s your name, man?” “Alexander Hamilton.”

Bill Reynolds’s “Find a Cause” spotlights suffragettes

Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

Illustration By Joe Rocco

By now, Hamilton’s path from creator Lin-Manuel Miranda’s thought nugget to a game-changing musical is well known: Miranda’s beach read—Ron Chernow’s Hamilton (Penguin, 2004), a hefty biography of the founding father—sparks a connection between history and hip-hop. But beyond musical and lyrical expression (and in this case, box office returns), why do projects like this matter? Why make music about history?

Musical activities build children’s listening skills in both mainstream classrooms and those including children with special needs, according to studies. Research also shows that young kids tend to remember the words to songs better than they do the words to stories, and songs also act as mnemonic devices that aid in knowledge retention. In addition, augmenting history lessons with music enhances kids’ skills in listening critically, analyzing lyrics, rhyming, and critiquing resources.

Building students’ interest in history’s big picture begins with presenting engaging depictions of the people involved. By constantly reexamining history and its characters, we may gain a better understanding of people and events—resulting in shifts from, say, celebrating Columbus Day to honoring indigenous peoples and their cultures.

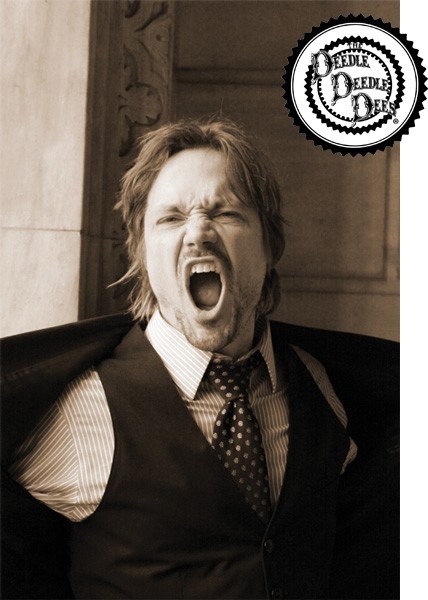

Lloyd Miller of the Deedle Deedle Dees

Photo and logo courtesy of Lloyd Miller

Several children’s music performers have made it their mission to express the excitement and intrigue of history through music. Lloyd Miller of the Deedle Deedle Dees uses historically accurate instruments, such as the bass fiddle and the banjo, along with good old rock and roll, to back his songs about important and sometimes-forgotten historical events. On stage, Miller tends to describe the stories behind his music, and how songs might even flow together as a unit. Bill Reynolds’s love of punk rock fuels his alter ego Professor Presley’s presentations of U.S. historical events from the Revolution to Reconstruction. Jonathan Sprout concentrates more specifically on historical figures and favors a middle-of-the-road pop sound. Finally, the late vocalist/lyricist Michael Earl sang biographies of well-known people, supported by Randy Klein’s Broadway-influenced, jazzy compositions on the duo’s sole collaboration, Michael Earl Sings Songs about Famous People (King Kozmo Music/Jazzheads, 2015).

Inspiration

What inspired these artists to create history-themed music for kids? Some fell into it; others had a specific purpose. While researching Gore Vidal’s Burr (Random House, 1973) for a film project, Miller found himself singing his thoughts about the book aloud. This habit informed Miller’s writing of a musical based on the Epic of Gilgamesh for his wife’s second grade class. That experience, he said, motivated him to create more songs about history for kids. Find out more about Miller’s passion for history by listening to the Deedle Deedle Dees’ Freedom in a Box (self-released, 2007), and follow it up with his own Sing-a-long History, Vol. I: Glory! Glory! Hallelujah! (self-released, 2015).

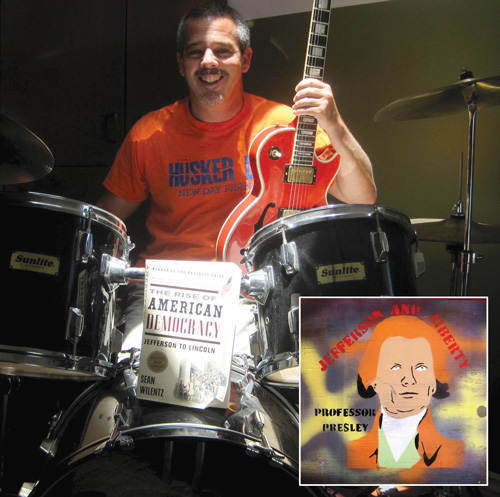

When he began teaching middle school history, Bill Reynolds couldn’t find music resources to accompany his lesson plans. Drawing on his DIY punk rock attitude and his love of Schoolhouse Rock!, Reynolds created his own crunchy power pop tunes to grab his students’ ears and energize his classroom presentations. The roaring “Ham N Jeff” describes the birth of political parties in our nation as ideological differences that arose between Alexander Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson as John Adams was elected our second president. The Ramones-like “Reconstruction Rock” succinctly and loudly runs down events that followed the Civil War. By resurrecting historical songs, such as the loud and triumphant Democratic Republican anthem “Jefferson and Liberty,” written in 1800, Reynolds shows that old news is current news, that our country was and always will be a nation of rebels fighting for truth and freedom. Here are a few salient lines:

“Here strangers from a thousand shores, Compelled by tyranny to roam, Shall find amidst abundant stores, A nobler and a happier home.”

Start with the album History Rocks (self-released, 2005), and then continue with the singles “The National Debt!” (self-released, 2012) and “Jefferson and Liberty” (self-released, 2013).

Sprout set out specifically to write songs about humans and not history, stating that “the history they made is the byproduct of their fascinating lives.” Interestingly, his biggest inspiration was Stephen Covey, author of the self-improvement runaway bestseller Seven Habits of Highly Effective People (S. & S., 1989), who helped Sprout better grasp the difference between hero and celebrity. Sprout’s “American Heroes” series musically describes the lives, achievements, and contributions of important figures, from the renowned (abolitionist Frederick Douglass) to the need-to-be-more-renowned (Girl Scouts founder Juliette Gordon Low). Begin with the familiar names on Sprout’s American Heroes I (self-released, 1996) and work your way through to American Heroes IV’s (self-released, 2014) less-prominent protagonists.

Bill Reynolds, aka Professor Presley

Photo and album cover art courtesy of Bill Reynolds

Intended audience

When Miller creates songs and performs them live, he considers everyone his audience. An example he cites is “The Rocket Went Up!,” the title track from the Deedle Deedle Dees’ latest album (self-released, 2016). The rhythm and tune of this song about women astronauts engage the youngest concertgoers, while the lyrical message pulls in elementary-aged kids and their parents. Who can resist a chorus like “Cool Papa! Cool Cool Papa!” (from “Cool Papa Bell,” on the Deedle Deedle Dees’ Strange Dees, Indeed [self-released, 2011])? One can imagine a preschooler humming those words on the way home from a singalong, then asking more about “Cool Papa” James Thomas Bell, the Negro League baseball legend who’s the subject of the song.

Reynolds originally saw his middle school students as the sole audience of his history-related songs, and he wrote tunes he felt would appeal specifically to them. The insistent, chugging verses and fist-raising chorus of “Find a Cause” perfectly express the powerful voices of the Reform Movement, including those of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott at the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848.

Besides appealing to upper elementary-aged kids, their families, and teachers, Sprout makes a point of including librarians in his target audience. Songs, such as the uplifting “Si Se Puede! (Yes, We Can!),” about labor leader Cesar Chavez, can be utilized in teaching units about biographical research, fact checking, poetry, world languages, political and personal expression, workers’ rights, music/lyrics, etc. To accompany his music, Sprout suggests fun, schoolwide activities such as a “Who Am I?” game, in which a series of clues are given about a particular hero during morning announcements or in the classroom, before playing the relevant song and revealing the figure’s identity.

These artists have seemingly endless recommendations for using their songs while teaching. On their websites, Sprout and Miller, in particular, feature dozens of lesson plans, activities, and links to related award-winning picture book biographies and middle grade nonfiction books. These musicians welcome questions and suggestions from classroom teachers and value input from educators.

Jonathan Sprout

Photo and album cover courtesy of Jonathan Sprout

Favorite moments and figures

So what do these musicians like to sing about the most? Reynolds says that he is drawn to the formation of the first political parties during the early republic because it was a “very contentious period with a lot of accusations and dirty politics. Sound familiar?”

Miller admires voting rights activist and civil rights leader Fannie Lou Hamer (he includes his song “Lucy & Fannie,” a tune he wrote with a group of Brooklyn fourth graders, in live performances). Miller adds that he appreciates the resilient outlook of children, who view current events with a “perspective that sees the opportunities in situations that I, as an adult, might have viewed as mostly hopeless.”

Contemporaries Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglass top Sprout’s list of heroes. “[Anthony] helped people understand that when women are given their rights, everyone benefits,” Sprout says. “Douglass helped demonstrate that when black people are elevated to equal status—we still have a way to go on this one—we’re all elevated.”

As listeners learn or relearn key moments in our nation’s past, Miller wants them to “know that they are valuable and that their stories are worth telling.” Sprout hopes his audience understands that it is “important we hold on to our greatest dreams, and that we persevere with our dreams as many of our heroes preserved with theirs.”

All these performers sing about the individuals who make history, not just history itself, and they emphasize the importance of differentiating admirable characters from personalities who are merely famous. Engaging students through music may enhance their learning experience, leading to a richer discussion of what we know about history. As Miller says, “I think singing is one of the best ways to bring people together and start a dialogue.”

The Beat of History

Flocabulary is a web-based company in Brooklyn that produces and distributes teaching units and in-house-created songs for all academic subjects. Their history-related tunes and videos will catch the ears of Hamilton lovers, as the subject matter, lyrical flow, and production are similar to Miranda’s creations. Song subjects range from ancient world history (“Islamic Empires”) to civics (“A More Perfect Union”), to hot topics like globalization and ISIS, with accompanying animated videos featuring on-screen lyrics. The site even features a brief “Week in Rap,” highlighting current events. It’s got something for students from kindergarten through high school.

Based in San Francisco, the Mural Music and Arts Project offers “History through Hip Hop,” a program that focuses on learning about equity and barriers. The sessions give teens opportunities to explore and express their feelings and opinions while learning about history and how it relates to their lives. Songs such as the slow-rolling “What If” espouse collectivism and self-sufficiency, whereas head-bobbing, melancholy tunes like “Where Did My City Go?” articulate the powerlessness and community disintegration that accompany gentrification. These will appeal to high school students.

Warren Truitt is a musician and former children’s librarian at the New York Public Library. He works with Auburn (AL) City Schools.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!