Review of the Day: The Mad Wolf’s Daughter by Diane Magras

The Mad Wolf’s Daughter

The Mad Wolf’s Daughter

By Diane Magras

Kathy Dawson Books (an imprint of Penguin)

$16.99

ISBN: 978-0-525-53134-0

Ages 9-12

On shelves March 6th

Sometimes you just want to read a book that knows how to run.

There are many way to define the term “great writing” as it applies to children’s literature. Eloquent. Ennobling. Distinguished. These terms all work. Here’s another one. Booooooooring! Tell me you didn’t read at least one book as a child deemed a “great work of literature” only to find yourself snoring by page four. We’ve all been there. I do believe that there is a mistaken understanding out there that the slower a novel moves, whether it is for children, teens, or adults, the more worthy it must be in terms of literary achievement. Lest we forget, books with speed and velocity on their side can contain just as much emotional resonance as even the slowest of tomes. To back up this claim I present you with today’s book. It may be set in 13th century Scotland, the land of bogs, but nothing in Diane Magras’s high-spirited tale is ever (forgive me) bogged down. Fast on its feet, never slowing, never stopping to catch its breath, and yet filled to the brim with complex character development and personal growth, Magras pulls off one of the trickiest conjuring tricks I’ve seen. Behold! A book able to pull depth and meaning out of frenzy. Come one! Come all! You never saw the like.

12-year-old Drest is small and female, but underestimate her at your peril. She’s a canny lass, living as she does with her war-band brothers and her father, called The Mad Wolf. But even a canny child can be caught unawares. Without warning Drest’s father and brothers are captured by invading knights while she escapes unscathed. Left alone with one of the knights (wounded by one of his own) the girl cooks up a plan to exchange the man for her family. That means trekking off to Faintree Castle, a journey fraught with peril. Along the way Drest makes allies (the boy Tig with his crow Mordag and the accused witch/healer Merewen) and enemies (a ruthless bandit bent on pursuing Drest, a mob of villagers) alike. On her side Drest has stamina, cunning, and strength enough for all her companions. Yet she still has a lot to learn about the world, about her herself, and even about the family she believes to be so just. An Author’s Note at the back contains extensive information about the state of Scotland in 1210, Feudalism and Village Life, Women, Healing, Castles, Swords, The Landscape, and even the basis behind The Characters’ Names.

I wasn’t kidding before when I said that this book moves at a sharp clip. My six-year-old daughter has taken to watching me as I read middle grade novels for 9-12 year olds, asking every 30 seconds or so, “So what’s happening now?” (apparently actually reading the book to her is out of the question). With most stories that amount of time wouldn’t yield a lot of change. With this book, I honestly had new information to impart with every update. Then I read ahead 30 pages or so, so when she asked for a summary I had to tell her about the rescued boy with the crow and the witch who’s about to be burned and the bandit that almost catches them and more and more and more. All in 30 pages! Considering the fact that the book could potentially have come across as a long slog across the Scottish countryside, the fact that Magras is able to zip the reader from point to point effortlessly without sacrificing character development along the way is more than admirable.

There is another way in which the writer is able to keep the book moving. As an author, Magras utilizes a clever trick to keep the reader from dwelling too long in Drest’s head alone. To guide her choices (and her chances) Drest imagines the voices of her brothers and father in times of strife. What this means for the reader is a continually amusing, and very comforting (in its way) stream of advice and counter advice from men that won’t always agree with one another, even if they’re merely imaginary. And you’re certainly not bored.

Writers are often told that you should create characters with agency, and that reject passivity as part of their hero’s journey. Usually the hero will hear the call, reject the call, and then find something inside of themselves that makes them follow the call. Drest isn’t really like that. Pretty much from the get-go she is determined to use Emerick (the knight) to get to Faintree Castle to rescue her family. There are some moments later on when she feels a bit down, but at no point does there come a time when she thinks better of this plan. It’s interesting to be placed so squarely inside the head of someone with so few doubts. Of course, that’s Magras’s secret plan on the sly. Drest at first is steadfast in her vision of right and wrong. Then, through a series of events, she comes to doubt everything she took for granted.

One of the central themes of the book is the question of morality in the face of family loyalty. Separated for the first time in her life from her brothers and father, Drest encounters but the outward perception of her family by the masses. In some cases villagers are sympathetic towards her on behalf of what they owe her family. In other cases, quite the opposite is the case. As she collects stories about her family’s actions, some are true and some are not but it is often impossible to distinguish. This places Magras in a tricky situation. If Drest’s family really does consist of true brigands, then the only solution is to permanently separate her from them in some way by the story’s end. So the author must play it both ways. The family must be vindicated for the most part, but be guilty of some kind of horrid crime as well. Drest’s father, it turns out, admits to some innocent deaths, albeit unintentional ones. So Magras is able to maintain the theme of Drest learning that her family is fallible while also keeping her with them (for the time being).

I won’t say it’s flawless, of course. Few books for kids are, let alone debuts. So I was, admittedly, somewhat baffled by the fact that at no point Drest (or anyone else for that matter) raises any questions about of her mother, except for a very brief mention that she never knew her (or, it is implied, cared to). Yet for a story set in 1210, it is strange that no mention comes of Drest’s closest familial relation. Mind you, the ample Author’s Note at the back does a very good job of distinguishing the roles of different kinds of matrons and maidens in the medieval era. Readers can read into those what they will. Or just assume that Ms. Magras is saving the info for a future book in the series.

I was trying to think of books similar to this one and a title that sprang immediately to mind was Tamora Pierce’s Alanna: The First Adventure. When it comes to girl-with-sword tales, nobody tops the Pierce. Yet as I thought about it I came to slowly realize the pop culture character that sits even closer to Drest’s soul. Rey from the new Star Wars films wield a light saber and not a sword, but deep down she and Drest are mighty similar. So to the librarians of the world I say this: Know a Star Wars girl hungry for some strong female characters? Hand them this, hand them Alanna, hand them The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle and then just keep on going. Girls with swords unite!

You know what’s hot this year? The 13th and 14th centuries in Europe. Boy, kids today that hunger for a little horse dung and serfdom are certainly in their element this year. Between this book and the also charming The Book of Boy by Catherine Gilbert Murdock, I don’t think I’ve seen Medieval life encapsulated so beautifully and so frequently. This book, being historical fiction, has a distinct disadvantage when held up alongside Murdock’s book or The Inquisitor’s Tale by Adam Gidwitz. I might be wrong but there’s not a single heavenly body in disguise on any of these pages. Kids sometimes get the impression that historical fiction is dull on some level. To those kids I hand Drest. Dirty. Filthy. Dead set. Warrior. Drest. A book for those kids that yearn for adventure, as well as children that would prefer their adventures to be played out by somebody else. By the end of this book Drest learns that “sometimes words alone can save your life.” The words on these pages may bear that out. A magnificent debut.

On shelves March 6th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Like This? Then Try:

- The Inquisitor’s Tale by Adam Gidwitz

- Alanna: The First Adventure by Tamora Pierce

- The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle by Avi

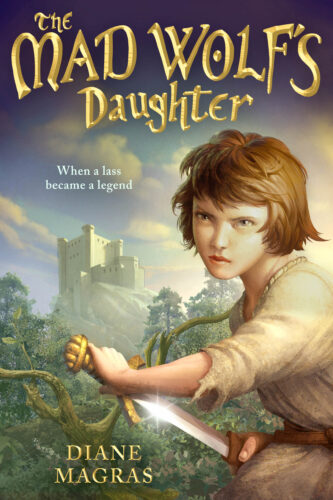

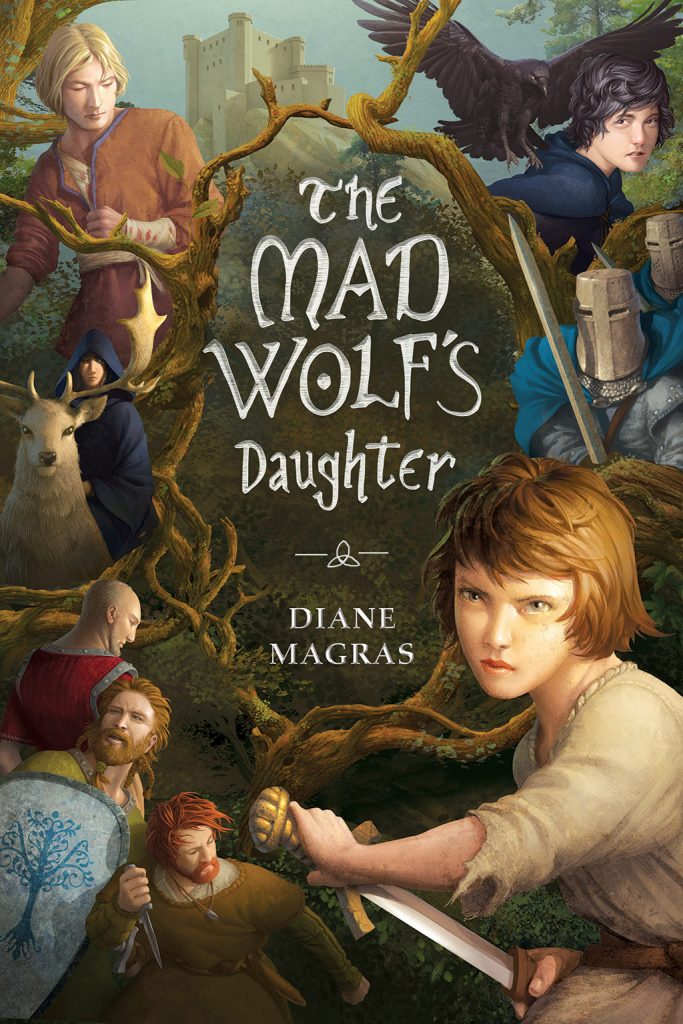

Notes on the Cover: In the Acknowledgments section of this book, author Diane Magras pours out a great deal of thanks to all kinds of people in her life. Then (at least in the early galley I read) she says this: “I’ve known my whole life the power of a book cover, and I am immensely grateful to Antonio Javier Caparo for putting his extraordinary imagination and skill into the work of art that is my cover. Thank you, sir, for interpreting these characters so beautifully, and giving readers the perfect introduction to Drest’s world.” If this portion of the Acknowledgments makes it into the final copy of the book, some readers might scratch their heads in confusion. Characters? What could she mean? Isn’t that just Drest on the cover? They wouldn’t be wrong. It is just Drest now, but look at an earlier version of this same book:

Now THIS cover is the entire reason I decided to read this book. I was absolutely enthralled by the characters I saw here. My daughter (who is six) and I had a great deal of fun picking out who each person in the book might be. It was a thrill. So imagine my confusion when they decided to strip all this hard work on the part of Mr. Caparo away and just leave us with Drest and Drest alone. It’s not hard to figure out why they may have done it. The initial cover with its woman on a stag and boy with a crow looks very high fantasy. The story itself, however, is pretty straight historical fiction. That said, I showed the final cover image to a fellow librarian and she immediately asked, “Is that a fantasy?” So clearly it didn’t really matter one way or another. Folks are going to assume from this cover that it’s a fantasy in any case. Another possibility is that they wanted to make it clear that Drest is the heroine of this tale, and not these other blokes. I appreciate the intention, but I think Caparo foregrounded Drest clearly enough in the initial book jacket that this was not a difficult detail to miss. I mean, the title is about a daughter, and she’s clearly a girl.

The author, for her part, has been nothing but nice about this change. You can see her thoughts on it here. She’s a good sport. She has to be. It’s her debut after all. She may well believe that this is a good change, but for my part I think a mistake was made here. It is nice to know that these guys will appear on the book flaps in some way, but they looked better on the cover.

Ah well. Can’t win them all, I guess.

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!