Review of the Day: The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge by M.T. Anderson and Eugene Yelchin

The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge

The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge

By M.T. Anderson

Illustrated by Eugene Yelchin

Candlewick Press

$24.99

ISBN: 978-0-7636-9822-5

Ages 10 and up

On shelves September 25th

In my job I read a lot of books written for kids and middle schoolers. To guide this reading I take into account a lot of professional reviews from sources like Kirkus and Publishers Weekly and School Library Journal and the like. If a book gets multiple stars, I flag it for my To Be Read pile. This is a good, effective method for finding great books but it is not without its flaws. I am in constant danger of Realistic Fiction Burnout (RFB). RFB comes when an adult subject has been exposed to a large number of children’s books involving realistic characters in realistic settings, all set in the present day. If I have to read one more bullying, school bus, lunchroom scene I’m going to melt into a large, rather unattractive puddle. I read outside my comfort zone, but truth be told I just wish I was reading more fantasy and science fiction. Those are my sweet spots. So when I just can’t take it anymore and the world is just too depressing and real, I turn to something like The Assassination of Brangwain Spurge for relief. Essentially a book that takes a Tolkien concept and wraps it up in a healthy bit of Cold War paranoia, M.T. Anderson and Eugene Yelchin have created what has to be the kookiest interpretation of Middle Earth-esque events to hit the children’s book scene since Ben Hatke’s Nobody Likes a Goblin. This book’s like that only longer and with a plot that feels like what you’d get if you combined The Rite of Spring with Yakety Sax. If that and the concept of a fantastical buddy comedy between an elf and a goblin (who are both historical academics) done in the visual vein of Brian Selznick appeals, then buddy have I got the book for you.

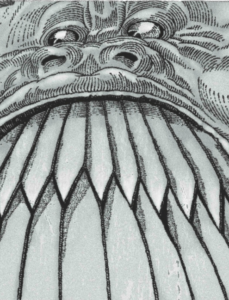

Open this book. It’s the darndest thing. The first thing you really see is what looks like a large, floating, warty Faberge egg. As you watch, the egg opens to reveal a jewel inside. And inside the jewel are grotesque carvings of a battle, pieces of fighters so inundated with spears and arrows that it resembles nothing so much as a pile of Pick Up Stix. That’s the Prologue, but Chapter One is equally visual. Now we are in a strange kingdom where elves load one of their companions into a barrel. He is handed the warty egg then launched into the sky, whereupon his vessel is plucked from the ether by a three-headed bird. This is where the text comes in and it is split in two. On the one hand we have the epistolary missives of the elf Ysoret Clivers, the Earl of Lunesse, who is dictating how an ancient artifact was found in Elfland and is now being sent with academic historical Brangwain Spurge to the land of the goblins to present to their leader as a peace offering. The other narrative follows Werfel the Archivist, the goblin historian who will be hosting Spurge, and who couldn’t be more pleased with the honor. A tentative peace has been laid between the two hostile countries and Werfel believes no one is better suited to treat his guest than he. But things don’t go exactly to plan. Alternating between text and images that represent Spurge’s point of view (which is not exactly reliable) readers receive a palpable understanding of what happens when two entirely different cultures have to fight through false assumptions and propaganda to reach a solid friendship.

There is an art to a good unreliable narrator. I suppose someone somewhere has probably written rules on the subject. First and foremost, the author has to decide whether or not they want to let the reader in on the narrator’s skewed p.o.v. from the start (think Timmy Failure) or if they want the reader to experience a kind of creeping suspicion and dread as they read (think Pale Fire). What sets Brangwain Spurge apart from the pack is that you’re dealing far less with an unreliable narrator’s words and more an unreliable narrator’s eyes. In fact, aside from the occasional letter from Earl of Lunesse, all thoughts come directly from the brain of the incredibly kind-hearted Werfel. But look how the book is set up. From the moment you open it you encounter not anyone’s words, but the images of Yelchin. Images that consistently undermine Werfel’s testimony. It’s as if the creators of the book are challenging young readers to question everything, even their own eyes. Why is it that we are so inclined to believe what we see over what we hear? We know better in the 21st century than we ever did in the 20th that images are unreliable. That they can be twisted and turned and changed to fit our needs. So here we have a book that takes a Brian Selznick style (more on him in a moment) and then slowly reveals to the reader that these pictures are frauds. The unreliable visual narrator is a new creation in children’s books, as far as I’m concerned. New, and extraordinarily vital in our post-Photoshop existence.

There is an art to a good unreliable narrator. I suppose someone somewhere has probably written rules on the subject. First and foremost, the author has to decide whether or not they want to let the reader in on the narrator’s skewed p.o.v. from the start (think Timmy Failure) or if they want the reader to experience a kind of creeping suspicion and dread as they read (think Pale Fire). What sets Brangwain Spurge apart from the pack is that you’re dealing far less with an unreliable narrator’s words and more an unreliable narrator’s eyes. In fact, aside from the occasional letter from Earl of Lunesse, all thoughts come directly from the brain of the incredibly kind-hearted Werfel. But look how the book is set up. From the moment you open it you encounter not anyone’s words, but the images of Yelchin. Images that consistently undermine Werfel’s testimony. It’s as if the creators of the book are challenging young readers to question everything, even their own eyes. Why is it that we are so inclined to believe what we see over what we hear? We know better in the 21st century than we ever did in the 20th that images are unreliable. That they can be twisted and turned and changed to fit our needs. So here we have a book that takes a Brian Selznick style (more on him in a moment) and then slowly reveals to the reader that these pictures are frauds. The unreliable visual narrator is a new creation in children’s books, as far as I’m concerned. New, and extraordinarily vital in our post-Photoshop existence.

For Anderson’s book to work he needed an artist that knew how to indulge in pleasant grotesqueries. And since Stephen Gammell has long been out of the business of creepy, Yelchin makes a fascinating substitute. So let’s examine exactly what happens when you read this book. You open it up and encounter a series of illustrations that remind you, possibly, of the works of Brian Selznick. Yet for all that they are cinematic in scope and done in black and white, Yelchin’s art here is almost the anti-Selznick. Where Brian luxuriates in bringing forth subtle curves through the most delicate of crosshatches, Yelchin appears to have channeled Hieronymus Bosch by way of Terry Gilliam. And as I mentioned before, Selznick’s art is all about trust. The young reader trusts that if they pay attention to the art in his books, they’ll be able to solve the mysteries hidden in his words. I suspect that Anderson and Yelchin are playing with readers’ past experience with Selznickian books. If this book had been done as a graphic novel, it simply couldn’t have worked quite as well. Sure, there are plenty of comics where the art is filtered through an unreliable narrator’s perceptions, but when you do it through a book that is made up entirely of sequential art then you’ve no chance to surprise the reader later on. Whatever you may call this book (I think “illustrated novel” suits it best) the format fits the telling.

When I go into a review of a book I like to do so cold, without having seen anything that might influence my opinions of the piece. Usually. When I am stumped, however, I’ll grasp at anything that might possibly help me in my interpretation. Take the art of this book, for example. What . . . what is it, exactly? I saw that my edition of the book included a little conversation between Anderson and Yelchin and I figured maybe they’d let slip what it is that Yelchin’s doing here. No dice, though they do have a nice debate over whether or not the book invokes the works of Faxian and Herodotus or John le Carre (the jury is still out on that one). Likewise, Anderson discusses how it is “a tragic meditation on how societies that have been trained to hate each other for generations can actually come to see eye to eye” while Yelchin calls it “A laugh-out-loud misadventure of two fools blinded by ideology and propaganda.” All righty then. This is probably the best explanation of what’s going on here that I could come up with. Yet for a book like this to work you need to get beyond clever details and grand gestures. You need heart and maybe a little soul. And to my infinite relief, I found both.

When I go into a review of a book I like to do so cold, without having seen anything that might influence my opinions of the piece. Usually. When I am stumped, however, I’ll grasp at anything that might possibly help me in my interpretation. Take the art of this book, for example. What . . . what is it, exactly? I saw that my edition of the book included a little conversation between Anderson and Yelchin and I figured maybe they’d let slip what it is that Yelchin’s doing here. No dice, though they do have a nice debate over whether or not the book invokes the works of Faxian and Herodotus or John le Carre (the jury is still out on that one). Likewise, Anderson discusses how it is “a tragic meditation on how societies that have been trained to hate each other for generations can actually come to see eye to eye” while Yelchin calls it “A laugh-out-loud misadventure of two fools blinded by ideology and propaganda.” All righty then. This is probably the best explanation of what’s going on here that I could come up with. Yet for a book like this to work you need to get beyond clever details and grand gestures. You need heart and maybe a little soul. And to my infinite relief, I found both.

Because for all that this book is visual Pop Rockets to the old eye sockets, it’s the relationship between Spurge and Werfel that props everything up. At the start of the tale Werfel (who is rather adorable) is just so giddy with the prospect of meeting Spurge that he imagines a glorious future where the two of them talk about his favorite things. “Finally: contact with the enemy. With another scholar. With someone else who loved antiquity and beautiful things, and who shared his hope for this beleaguered world.” When Spurge misinterprets everything he sees and rebuffs Werfel’s attempts at friendship, the goblin scholar sours on his guest. Yet their fates are tied closely to one another and slowly Werfel is able to peel away the skin of his guest’s prejudices with sheer kindness. My favorite part of the book is the moment when the two finally start to bond by “pretending to make friendly reading suggestions to each other while actually just trying to make the other feel stupid. It was the best evening either of them had enjoyed in a very long time.” By the time you get to the end of the book, the relationship is sealed, and you, the reader, are glad of it.

I’ve often said that the best way to get kids to read about adults having adventures is to turn them into furry woodland creatures (see: Redwall). But making your characters mythical creatures works just as well in the end. Anderson has always flirted with his love of fantasy, though until now it was mostly relegated to his Norumbegan Quartet. Here he takes a deep dive into a full-fledged fantasy world. I admired many of his choices along the way. For example, it would have been so easy for both Anderson and Yelchin to have given the goblins a free pass in this book. So maligned in the works of Tolkien and subsequent Tolkien imitators, the twist of making them more sympathetic than the elves is sweet. What upsets the applecart a bit is the fact that while the goblins may be more open-minded than the elves, they are also living in a police state with ruler so strange that I’m still trying to find a metaphorical or real-world equivalent to his Mighty Ghohg. Methinks I’m barking up the wrong tree with that, though. Methinks.

I’ve often said that the best way to get kids to read about adults having adventures is to turn them into furry woodland creatures (see: Redwall). But making your characters mythical creatures works just as well in the end. Anderson has always flirted with his love of fantasy, though until now it was mostly relegated to his Norumbegan Quartet. Here he takes a deep dive into a full-fledged fantasy world. I admired many of his choices along the way. For example, it would have been so easy for both Anderson and Yelchin to have given the goblins a free pass in this book. So maligned in the works of Tolkien and subsequent Tolkien imitators, the twist of making them more sympathetic than the elves is sweet. What upsets the applecart a bit is the fact that while the goblins may be more open-minded than the elves, they are also living in a police state with ruler so strange that I’m still trying to find a metaphorical or real-world equivalent to his Mighty Ghohg. Methinks I’m barking up the wrong tree with that, though. Methinks.

As strange as this may seem, the book that this reminded me the most of was the series of Avatar: The Last Airbender comics by Gene Luen Yang. Those books spend much of their time examining at length the intricacies of deconstructing an oppressive colonial system in a fantasy world, something that this book only touches on lightly. Yet even so, we live in a post-colonial world (for the most part). Colonialism didn’t go that well, and post-colonialism was botched in a variety of interesting and horrible ways. Which brings us to America in 2018, the year of this book’s publication. For kids reading this book today, a title that discusses prejudices born out of (often willful) ignorance coupled with warmongering and malicious leaders . . . golly, is there anything here that will speak to them? I won’t lie. This book will take some work to get through for some kids. Even dyed-in-the-wool comic book readers may stumble a little initially at the unfamiliar art style. But there will be a cadre of kids that stick with it. Kids that find the story of scholars in fantasy realms fascinating. And those kids are the ones that will cut through the treacle and figure out what this book is actually trying to say. I’d wager good money that more kids will get it than adults. A fascinating blend of the wholly original and what is normally overly familiar, Anderson and Yelchin are having way too much fun here. It shouldn’t be allowed. And I sure am glad that it was.

On shelves September 25th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!