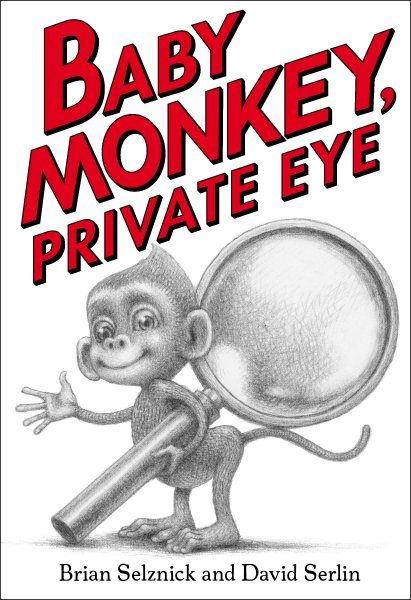

Review of the Day: Baby Monkey, Private Eye by Brian Selznick and David Serlin

Baby Monkey, Private Eye

Baby Monkey, Private Eye

By Brian Selznick and David Serlin

Illustrated by Brian Selznick

Scholastic Press

$16.99

ISBN: 978-1-338-18061-9

Ages 3 and up

On shelves February 27th

Brian Selznick. Honey. We’ve got to talk.

Now look, it was all well and good when you started getting a little crazy and shaking up notions of what an “illustrated book” actually means. Winning the Caldecott for a novel? Never been done before. And the fact that Hugo Cabret and its companion novels Wonderstruck and The Marvels push every conceivable envelope, in terms of what a visual novel can be, is not just noteworthy but historic. But now you’re getting all slick on us. It wasn’t enough to conquer the middle grade illustrated novel, eh? Now you’re just fudging the lines between early chapter books and picture books in ways I’ve honestly never seen before. Baby Monkey, Private Eye is, as anyone looking at the cover could tell you, freakishly adorable. And funny. But it may also be the most subversive little number to hit our shelves in a very long time.

Got a crime? Then who you gonna call? Forget Sam Spade and his ilk. The true brains in this town belong to Baby Monkey. He’s a baby, he’s a monkey, and he’s a crime fighting genius. With every client that crosses the threshold of his office, he has a routine in place. Examine the evidence. Take notes. Have a snack. Put on some pants (that particular part of the job is a bit on the trying side). And solve that crime! Baby monkey always gets his man (slash zebra/lion/snake/mouse). But when his final case involves a missing baby, that’s when things start getting personal.

Have a seat. I need to tell you a story. About three years ago I got wrapped up in a wave of hubris that almost knocked me flat. I had been suggested by an academic friend to contribute a chapter to a Routledge resource on picture books. Please bear in mind that I have almost no experience with academia in any form. Blithely I agreed and was subsequently floored when it became eminently clear that I was in over my head. My assigned chapter was “Picturebooks and Illustrated Books”, a distinction that I wasn’t overly familiar with. It all worked out in the end (thanks to the intervention of a friend who knew this territory better than I) and I got a crash course in the difference between an “illustrated book” and a “picture book”. Would that Baby Monkey, Private Eye had been available when I was determining these distinctions. As it turns out, there is a very good reason that press for this book calls it “a winning new format”. I’ll break it down for you.

Let us first pick up our copy of the book and just give it a good going over. As you can see, it’s your standard 5-1/4 X 7-3/4 inch sized novel. 192 pages in length. Seems pretty standard stuff. And yet from the moment you open it up it’s pretty clear that the bulk of the book is going to be art rather than text. Though it contains five chapters, a Key, an Index, and a Bibliography (more on that later) the actual book is perfect for very young readers. It is also perfect (and I cannot stress this enough) for reading ALOUD to large groups of very young readers. This realization had me pondering what it would have looked like if Selznick and Serlin had kept the page count but pulled a Bolivar and made the pages picture book-sized. Certainly that would have taken much longer to create (lotta cross-hatching would ensue) but in an era when the walls between formats is a lot more fluid than in the past (thanks in large part to the aforementioned Hugo Cabret) it certainly could have been done. And yet, the creators clearly wanted this to be an early chapter book. Selznick actually got his start back in the day with The Houdini Box, which was early chapter fare of a different sort. And reading this book with my 3-year-old and 6-year-old (who both loved it equally) this book may indeed be one of those pan-age level titles that transcend audience. Doggone it.

Let us first pick up our copy of the book and just give it a good going over. As you can see, it’s your standard 5-1/4 X 7-3/4 inch sized novel. 192 pages in length. Seems pretty standard stuff. And yet from the moment you open it up it’s pretty clear that the bulk of the book is going to be art rather than text. Though it contains five chapters, a Key, an Index, and a Bibliography (more on that later) the actual book is perfect for very young readers. It is also perfect (and I cannot stress this enough) for reading ALOUD to large groups of very young readers. This realization had me pondering what it would have looked like if Selznick and Serlin had kept the page count but pulled a Bolivar and made the pages picture book-sized. Certainly that would have taken much longer to create (lotta cross-hatching would ensue) but in an era when the walls between formats is a lot more fluid than in the past (thanks in large part to the aforementioned Hugo Cabret) it certainly could have been done. And yet, the creators clearly wanted this to be an early chapter book. Selznick actually got his start back in the day with The Houdini Box, which was early chapter fare of a different sort. And reading this book with my 3-year-old and 6-year-old (who both loved it equally) this book may indeed be one of those pan-age level titles that transcend audience. Doggone it.

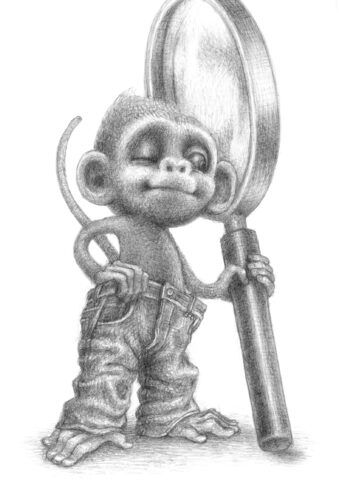

Why do both of my small children love this book so much? Because it’s a gut-buster, frankly. Funny? Sister, you don’t know the half of it. The very opening of the book sets the stage for hilarity. You open it up and are accosted by an oversized call to “WAIT!” It then challenges you with the question “Who is Baby Monkey?” The answer? “He is a baby.” Page turn. “He is a monkey”. Page turn. “He has a job to do.” That’s when you see his detective agency. Now as any good children’s book author knows, when writing a funny book for children, ideally you should direct some humor at the kids and some at the adult readers. Go too far in the children’s direction and you get Walter the Farting Dog. Go too far in the adult direction and you get some crappy Dreamworks movie that’s more of a prolonged wink than a film. In this, Serlin and Selznick find the perfect sweet spot. For the adults there’s a kind of seek-and-find element to Baby Monkey’s ever changing office. For kids, there’s the fact that baby monkey cannot easily put on his own pants. Pants are, by their nature, hilarious. I think it has something to do with the word itself. Pants. And while most jokes work best when you’re operating under the Rule of Threes, the choice to give this book five chapters (which involves four pant-struggling sequences) is bold. Surely there was a temptation somewhere in the process to limit the chapters to three. I respect the fact that it’s an unwieldy five instead. Gives the jokes more time to percolate.

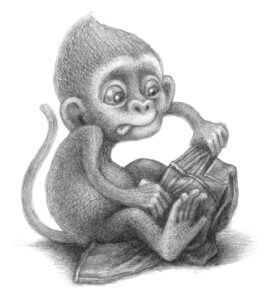

Monkeys should, by all rights, be classic picture book staples. With that in mind, I ask you this: Who is the most famous monkey in the whole of children’s literature. If you said Curious George I’m gonna whip out the old “Curious George is actually an ape” line and we’ll have at it. But beyond George there are shockingly few famous kidlit monkeys to choose between. This is particularly strange because monkeys should potentially fill all the requirements of children’s book illustration. They are small, like human children, and cute, like human children. They are, in fact, the perfect stand-ins. Selznick, for his part, has gone and gotten cute on us. His baby monkey is remarkably tiny. Do you remember that old Disney-drawn explanation of “The Cute Character” where the ratio of the head to body, ears to head, legs to feet, etc. are explained? Well, Selznick clearly knows his stuff. Baby monkey’s proportions are carefully calibrated for maximum cuteness, as are his facial expressions, and body language. This is part of the reason the book works as well as it does with the youngest of readers. Who wouldn’t love that guy?

Monkeys should, by all rights, be classic picture book staples. With that in mind, I ask you this: Who is the most famous monkey in the whole of children’s literature. If you said Curious George I’m gonna whip out the old “Curious George is actually an ape” line and we’ll have at it. But beyond George there are shockingly few famous kidlit monkeys to choose between. This is particularly strange because monkeys should potentially fill all the requirements of children’s book illustration. They are small, like human children, and cute, like human children. They are, in fact, the perfect stand-ins. Selznick, for his part, has gone and gotten cute on us. His baby monkey is remarkably tiny. Do you remember that old Disney-drawn explanation of “The Cute Character” where the ratio of the head to body, ears to head, legs to feet, etc. are explained? Well, Selznick clearly knows his stuff. Baby monkey’s proportions are carefully calibrated for maximum cuteness, as are his facial expressions, and body language. This is part of the reason the book works as well as it does with the youngest of readers. Who wouldn’t love that guy?

The art is indicative of Selznick’s trademark graphite, with one notable difference. Color! That’s right, baby, there’s at least one singular jolt of color making itself known in each chapter. I had just assumed that the red of the missing jewels / pizza / clown nose / etc. was the same as the red on the cover of the book, but this does not appear to be the case. While the red of the letters on the cover are deep, the jewels / pizza / nose have this extraordinary tint to them. Maybe just a hint of orange? I couldn’t say, but whatever it is it just pops off the page. I think longingly of what this book could have been had the author written it in a picture book format. Then I get ahold of myself again and appreciate it for what it is.

I mentioned earlier that in writing a book for children that’s funny, an author has to walk a fine line between humor for kid readers and humor for adult readers. In the case of Baby Monkey, though, this applies to far more than the jokes. In his art, Selznick takes care to hide in plain site multiple references to whatever case it is that Baby Monkey is about to solve. His office before the opera singer comes in is outfitted with portraits of Maria Callas and Marian Anderson. A bust of Mozart overseas Baby Monkey’s note taking. There’s even a reference to that old Marx Brother classic (my personal favorite) A Night at the Opera. With each case the décor changes. Don’t think for a moment that I’m good at spotting all these references, though. While I got the poster for the 1980 production of Barnum and recognized the image from A Trip to the Moon (a bit of an homage to Hugo Cabret in its way) I had to rely heavily on Selznick’s “Key to Baby Monkey’s Office” at the back of the book. There you will find all the hidden references laid out before you. It’s really nice, actually. Few artists take the time to let their readers in on their jokes. But the book’s most subtle jokes for adults are also the most superfluous (and, consequently, the most charming). After the aforementioned “Key” you’ll find an Index and Bibliography that honestly have no reason at all to be there. The Index may be worth it entirely for the entry on “Wainscoting” (Warning: it’s intense). The Bibliography, however, is a carefully crafted labor of lovable nonsense. It is filled from guggle to zatch with nonsense books. From a 1997 edition of Animals Who Look Like They Have No Noses (2nd edition, if we’re going to be specific) to Moshe Moshi’s Famous Babies I Have Known the faux titles, authors, and presses abound. Honestly, just read it for the authors’ names. Barbara Bathtowel. Luis Gergle. Herbert Hobbypocket. I could go on all day.

I wonder if there’s a moment where a children’s book creator peaks and then crosses over to a whole new level. Sendak sort of did it, the consequence being that he traded his mortality for some truly obtuse works for kids. Selznick is traveling on a Sendakian course, but along the way he’s never lost his penchant for kid-friendly fare. Credit collaborator David Serlin (who’s getting the short end of the stick in this review) or credit is unequivocal love for the audience (a weapon Sendak never had in his own back pocket). For all its seeming simplicity, Baby Monkey packs a wallop. It challenges what an early chapter book can be, it’s the funniest fare you might read this year, it’s beautiful to look at, and there’s plenty to please small children and grown adults alike. Taken as a whole, the Serlin/Selznick duo is a force to be reckoned with. Will we see more Baby Monkey in the future? I cannot know the answer. All I can hope is that these guys pair up frequently. I like where all this is headed.

On shelves February 27th.

Source: Galley sent from publisher for review.

Interviews:

Shelf Awareness sat down with the creators of this book for a bit of a tête-à-tête. You can find the full text here.

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!