Meet the Recipients of the 2015 SLJ Build Something Bold Award

Diana Rendina, media specialist at the Stewart Middle School library in Tampa, FL.

Stewart Middle School photos by Mark Arbeit

Winner Stewart Middle School Library, Tampa, FL

STEM Central

Librarian Diana Rendina turned a “cavelike” space into a vibrant maker hub

A maker space with a LEGO-covered wall and whiteboard-topped tables spells it out to visitors at the library at Stewart Middle School (SMS) in Tampa, FL: this campus takes its STEM-learning theme seriously.

The revamped library, media center, and maker space is the brainchild of Stewart’s media specialist, Diana Rendina, who also received the 2015 American Association of School Librarians’ (AASL) Frances Henne Award for librarians in their first five years on the job. Since she began working at Stewart, Rendina, who also grew up in Tampa, has transformed the library she described as “dark” and “cavelike,” with some volumes that hadn’t been checked out since the 1970s. Although Stewart has been a Science/Technology/Engineering/Math (STEM) magnet school since 2000, Rendina says, “there was hardly anything in the library that would let you know you were in a STEM school, aside from the science books and a couple little displays.”

Now, “at any given time, students are building arcade games out of cardboard, programming remote-controlled cars they have designed, or creating an artificial coral reef out of LEGOs,” says Christine Van Brunt, former library media services supervisor for Hillsborough County Public Schools, including SMS.

Student-driven design

After weeding outdated titles from the collection, Rendina asked the students what they wanted. For starters, they requested more than a single shelf of graphic novels and manga. They insisted that drab beige walls be livened up with bright blue and green paint. And they wanted a maker space.

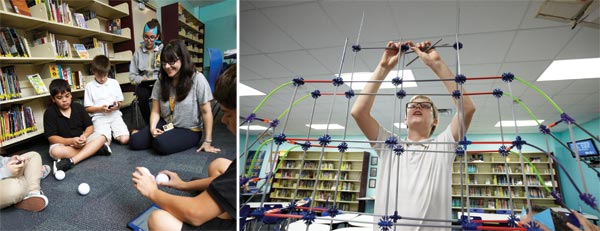

In early 2014, Rendina pushed a few old library tables together, and SMS’s lead science teacher donated LEGOs and K’Nex that had been gathering dust in a storage room. “The kids took to it right away, the very first day of our putting those out,” says Rendina. The maker space was born—or “popped up,” in current lingo.

The real transformation of the 3,500-square-foot library started during the summer of 2014 with a $5,000 grant from Lowe’s Toolbox for Education, which paid for the fresh paint and new furniture. Out went the wooden tables that were too heavy to move for group projects, replaced by ones on casters and stacking chairs. “It’s really easy to let students have more ownership of the space,” says Rendina, noting that it works well for teachers, too: “I also use it as a flexible collaborative space.”

Rendina testing Sphero robotic balls with students (left); a creation from the maker space (above).

A LEGO board for art and messaging

Inspired by a photo of a child’s bedroom on Pinterest and funded by grants from Donors Choose, Rendina covered one wall of the library with LEGO baseplates, creating a 80" x 80" surface where students and visitors can build, make pixel art, or leave messages. “I love that every time a kid comes in now—it doesn’t matter what age they are—they always get excited about it,” she explains. In total, the school raised over $5,000 through Donors Choose to also fund tech tools, such as Spheros, Cubelets, Snap Circuits, and MaKey MaKeys, Arduinos, and four iPod Touch devices. A whiteboard wall and the tabletops were funded by Lowe’s and, in part, donations from Contrax Furnishings, based in Gainesville, FL. As word spread, parents and other people in the community also donated more LEGOs, K’Nex, and craft supplies.

Since 72 percent of Stewart’s students qualify for free or reduced-price lunch, Rendina received $500 of Title I funds to help pay for supplies in the teacher workroom that is part of the library.

Rendina’s $5,000 yearly budget for books, magazines, and supplies is supplemented by an average of $4,000 raised through annual Scholastic Book Fairs. A Laura Bush Foundation grant provided another $5,000 to purchase books to appeal to the ethnically diverse student body, which is 36 percent black, 33 percent Hispanic, 21 percent white, seven percent multiracial, and three percent Asian.

Tech brings out reluctant learners

Rendina says the tactile, experimental nature of the space also encourages reluctant learners: while it feels like play, the students are grasping core scientific concepts. “If you ask them about it, you’ll see that they’re learning and they’re understanding concepts that they are working with,” she says. “They might not know the exact vocabulary yet, but they get things like symmetry and structures.”

Some students use the maker space during their club period, the last hour of school each Monday. Others drop in, using passes given out by teachers to students who finish their work early or for especially good behavior. There are always 20–30 kids in the library during lunch.

The library technology can also help draw out socially challenged youth. Rendina describes one sixth-grade boy who was very awkward but enjoyed building things on his own. During a Skype chat with a class from a local elementary school, this quiet 12-year-old was the first to raise his hand. “That was a really powerful moment,” says Rendina. “A lot of kids might not be good socially, but they are proud of the things they build.”

While Rendina is “a proven leader among her peers,” Van Brunt says, she is also always learning from others, citing Laura Fleming from New Milford (NJ) High School as a big influence, as well as books such as Design, Make, Play: Growing the Next Generation of STEM Innovators (Routledge, 2013) by Margaret Honey and David Kanter. She also likes visiting children’s and science museums to get new ideas. “I think it’s really important that we start to rethink our notion of what a school library is and what it does,” says Rendina. “It’s really exciting to see that shift. To see the transformation happen is like a rebirth.”

Rendina blogs about her work at Renovated Learning and as a regular contributor to AASL’s Knowledge Quest. She has also presented with other librarians at regional annual conferences, including the Florida Association of Media Educators (FAME) and the Gulf Coast Maker Con.

As for what Rendina plans to build with the $2,500 Build Something Bold award, she says she will consult with her student leadership committee.

First Runner Up Lewis and Clark Elementary School, Kansas City, MO

Angela Rosheim with items from the library maker space she created.

Photo by Susan Pfannmuller

Making to Learn

Embracing knitting, inventing, and productive failure

At Lewis and Clark Elementary School in Kansas City, MO, library media specialist Angela Rosheim has a bold idea. “We almost have a culture of failure in our library,” she says. “We want the kids to fail so they can learn to fix.” Just outside the 25' x 16' maker space is a wall where students can write messages about what they have failed at—and what they learned.

Rosheim herself never stops taking risks. “Everything she does is bold and powerful and impactful,” noted Kyle Palmer, principal at Lewis and Clark, in his nomination letter. During Rosheim’s more than 20 years at the school, library programming has evolved from storytime and checking out books to teaching research skills and creating a space for exuberant tinkering and productive experimentation. A core desire to learn drives the maker space. “When I first went into library science, it was because I loved books and I loved literature,” says Rosheim. “I still love books, but we need to keep growing.”

She started work on the maker space in the summer of 2014 and asked students what they would like to do there. They wanted to knit and sew, build robots, and write music. “I am not content to tell my students that something is not possible,” she says. “If they can think it, they should be able to create it!”

Rosheim paid attention to the chatter online about maker spaces, following blogs and Twitter accounts to learn more and visiting other maker spaces around Kansas City.

Students in maker mode at the Lewis and Clark Elementary School library.

Photos courtesy of Lewis and Clark Elementary School library

In 2014, she received an $8,000 grant from the school district foundation to convert an unused computer lab into a maker space. The room was soon filled with engineering toys, such as K’Nex, Tinker Toys, and LEGOs, plus robotics equipment including Sphero, Ollie, and Cubelets. The school PTA also purchased a 3-D printer. The library receives an average of $3,000 annually from the PTA, on top of its $10,000 annual budget.

The space also includes sewing machines, knitting needles and crochet hooks, and recycled boxes and cardboard tubes that students use to make anything from marble runs to make-believe arcade games. Those kids who struggle in traditional classroom settings may thrive in a hands-on environment where it’s OK to make mistakes, start small and try again, says Rosheim. “They want to make a sweater. Then they realize they are not at that level,” she says. “So they learn the stitches. Eventually we get some little scarves and bows.”

Now, Lewis and Clark’s maker space is a model facility for the state of Missouri. Forty schools have toured the facility and nearly 100 additional Kansas City–area teachers, librarians, and administrators are expected to visit in 2015–16.

Editor’s Choice C.C. Mason Elementary School, Cedar Park, TX

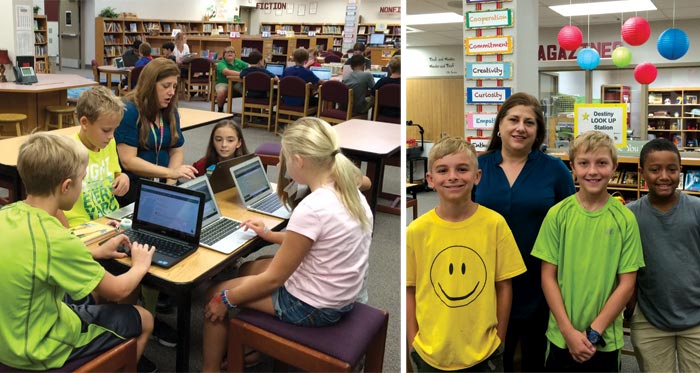

With student input, Tracey Rice (above center and right) created a more decentered library design.

Photos courtesy of C.C. Mason Elementary School library

Elementary Engineering

A library designed by students, for students

If you could build or create anything, what would it be?” That was what library media specialist Tracey Rice asked her fifth graders at C.C. Mason Elementary School in Cedar Park, TX, northwest of Austin, during the 2013–14 school year. The current library, prominently located near the school’s front entrance, is the answer to that question.

In keeping with Mason’s accreditation as an International Baccalaureate Primary Years Program (IB-PYP), Rice—Mason’s sole librarian—has transformed the library’s 2,700-square-foot space and its programming, with a focus on flexibility, hands-on learning, and student-led inquiry. Rice faced financial challenges: a 2008 budget cut halved Mason’s library budget, leaving her $5,000 each year—not enough for renovation or new furniture. That didn’t stop her from seeking creative, low-cost ways to update the space. “Lack of funding doesn’t have to be a barrier to change,” says Rice. “Look at how the library is used and what needs aren’t being met.” Volunteers donated materials, such as LEGOs, K’Nex, Snap Circuits, and two sewing machines.

During 2013–14, Rice worked with the students, using the Room Planner iPad app and a construction paper template of the library to explore ways to make the space more flexible and student-led. Described by colleagues as “willing to fail forward,” Rice also welcomed the input of teachers and volunteers. Two weeks later, the rearranged library had mostly shifted away from centralized work areas. The large circulation desk was broken into three smaller stations: two for student self-checkout and a third for library management, also serving as a self-serve circulation area during high-volume times. A neglected 280-square-foot office became a media production room, where fifth graders now broadcast daily video announcements. Desktop computers, previously dispersed around the library, were assembled to form a mini-lab for small group lessons. Because of the space opened up by the new configuration, two full classes can now comfortably use the library at any time.

Students also told Rice they wanted three main areas of activities: arts and crafts, engineering, and technology. “What surprised us most were the number of students who wanted to make things for others, including tree houses, toys, and a clubhouse for pets,” Rice says. Mason Elementary is a Title I school, where 33 percent of the student body is economically disadvantaged. Sixty-three percent of the students are white, 27 percent are Hispanic, and the others are African-American, Asian, or more than one race.

Kindergarteners through fifth graders now take part in STEAM-based activities during library time. Fifth graders can also join an afterschool enrichment Maker Camp at the library—which has evolved “from a quiet place to read and do research to an exciting place to collaborate and create,” Rice says.

Grace Hwang Lynch, a Bay Area freelance writer on race, culture, and parenting, blogs at HapaMama.com.

Grace Hwang Lynch, a Bay Area freelance writer on race, culture, and parenting, blogs at HapaMama.com.

About the Award

SLJ’s Build Something Bold Award, sponsored by LEGO Education, honors creativity in programming that incorporates hands-on learning led by the librarian or media specialist. The 2015 winner received $2,500 and a LEGO Education StoryStarter Classroom Set with software and curriculum. The first runner-up was awarded $1,000, and the editor’s choice selection received $500. The judges were:

Leshia Hoot, senior segment manager, preschool and elementary, LEGO Education Kathy Ishizuka, executive editor, School Library Journal Colby Sharp, teacher, Parma Elementary School, Parma, MI Holly Whitt, librarian, Walnut Grove Elementary School, New Market, AL; 2014 Build Something Bold Award winner Rebecca T. Miller, editor-in-chief, School Library Journal

For more information, visit slj.com/buildsomethingbold.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Denice Healey

Valuable analysis , For what it's worth , if anyone is requiring a FL DoR RTS-3 , my colleagues used a sample document here http://goo.gl/LumVKUPosted : Jul 10, 2016 09:31

Deanna Evans

Congratulations to all of the winners, especially to Diana, who I follow on Pinterest, often re-pinning and/or "liking" her pins. You all are brilliant innovators and your kids are lucky to have you working on their behalf!Posted : Sep 30, 2015 09:47