Eco-Action: Turning Students’ Climate Anxiety into Agency

From Brooklyn, NY to the West Coast, librarians are taking the lead on climate change education.

|

sarasw art/Getty Images |

Related article: |

Last year, the New York City Office of Library Services held a contest offering school librarians a chance to bring “Artemis Fowl” author Eoin Colfer to their school. But Colfer wasn’t visiting to talk about his popular series that features a young criminal mastermind.

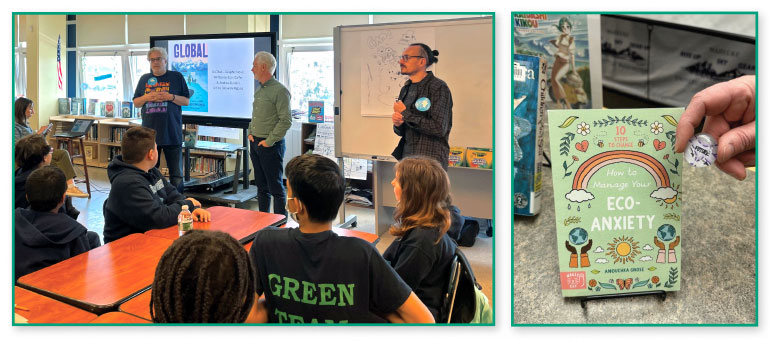

Instead, he was discussing his graphic novel Global, written with Andrew Donkin and illustrated by Giovanni Rigano, a story about the real-world impact of climate change.

Students at Scholars’ Academy, where Colfer spoke, already knew about the devastating effects of climate change. The grade 6–12 school in Rockaway Park, Queens, bracketed by Jamaica Bay on one side and the Atlantic Ocean on the other, was one of many in the area to be heavily damaged by Hurricane Sandy in 2012.

“Our kids have lived through the effects of climate change,” says school librarian Teresa O’Brien Israel. “It’s a passionate topic for our students, and since 2012, it has grown into this huge part of the school culture.” Israel’s students take on climate-conscious activities at school, like recycling, composting, and maintaining the school garden. They read print books about climate change the school library received as part of the raffle, and they browse a digital climate collection that every school in the city has access to.

When Israel and other educators teach kids about the effects of climate change, they must be mindful of the students’ mental health issues around the topic. According to the American Psychological Association (APA), climate change poses a significant threat to children and youth in the form of “eco-anxiety,” defined as a chronic fear of environmental doom. A 2021 report in The Lancet Planet Health found that of 10,000 children and young people from around the world, 84 percent were moderately worried, while nearly half said feelings related to climate change, including sadness, anger, and a sense of helplessness, affected their daily life.

Because of this, it’s critical that environmental curriculum not only addresses environmental realities, but also provides students ways to feel empowered to take action toward solutions. And much of what all school librarians already do, like teaching about informational literacy and leading inquiry projects, connects seamlessly with climate change education. From Brooklyn to the West Coast, librarians are taking the lead.

|

From Left: Author Eoin Colfer (standing, center) at Scholars’ Academy; Recommended reading from Tiffany CoulsonCourtesy of Teresa O’Brien Israel; Courtesy of Tiffany Coulson |

Messages of hope

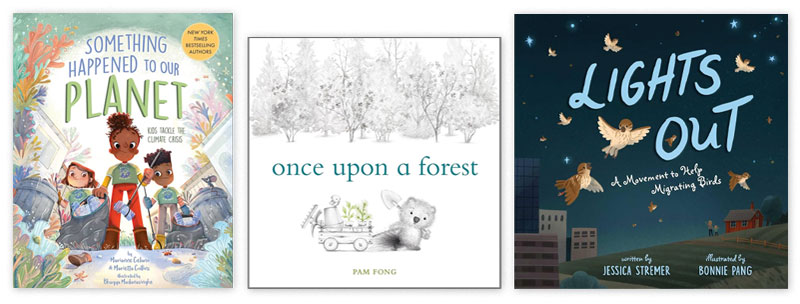

Tiffany Coulson, a librarian and curriculum designer in rural Washington State, says that books and lessons about the environment should be accurate and make students concerned enough to want to act, but not so overwhelmed that they lose hope.

“The APA says getting kids involved makes them feel less out of control, and that’s a big part of dealing with eco-anxiety,” says Coulson. “But without a message of hope, they may not feel like their engagement is going to do anything.”

Coulson seeks books that not only help students make positive connections to nature, but also highlight the adaptability of the natural world. One of those, Jason Chin’s Redwoods, from 2009, is even more topical today, now that scientists have discovered new evidence that the ancient trees are more resilient to catastrophic wildfires than previously thought.

Another example, Wombat Underground by Sarah L. Thomson, tells the surprising story of how the typically territorial wombat opened its burrows to other animals fleeing wildfires in Australia in 2020. Coulson says examples like the wombat and the redwoods “speak to how nature adapts and to resilience in ways we never anticipated.”

April Oliver, the media specialist at Lawrenceville (NJ) Elementary School, recalls learning about climate change as a student—in particular, the effects of acid rain—and staying up at night with worry. In 2020, New Jersey became the first state to bring climate change curriculum into every content area from kindergarten through high school. In her teaching approach, Oliver makes sure her youngest students get to learn about climate change without being traumatized.

One example of keeping her climate lessons positive is through a project on animal migration. In their classrooms, students learn about how climate change is forcing animals to find new sources of food and water. Oliver extends the lesson in the library by having them research ways countries are helping animals, like in Kenya, where people built tunnels to help elephants pass beneath a busy highway.

Oliver’s library has a “climate corner,” with a tree-shaped bookshelf and pillows shaped like logs, where students can read about climate change in a calm, safe space. Popular titles like Jayden’s Impossible Garden by Mélina Mangal and Stand Up! Speak Up! by Andrew Joyner help inspire and uplift students.

“In general, if you ask them about climate change, they say it’s everyone’s job to help the earth, which is exactly the message they should have at this age,” Oliver says. “We don’t want to scare young children into this doom-and-gloom idea that the future is hopeless.”

Israel’s Scholars’ Academy has encouraged student agency recently by creating a hydroponic lab and partnering with an NYC nonprofit, Teens for Food Justice, to grow food in the school garden for the local community. Israel also works closely with the student Green Team and the STEM teacher to bring STEM and environmental curriculum to the library.

|

Right: A student at Hopewell Valley Central High School presents climate activist Nyombi Morris with a painting of him; More student artwork.Courtesy of Hopewell Valley Central High School (NJ) |

Real-world connections

When librarians like Israel focus on climate change, they “are able to make real-world connections with the science classroom, and to promote students dealing with real-world issues and work on authentic projects,” says Vincent Hyland, a library coordinator with the NYC Department of Education (DOE). “[There is also] lots of spurious information out there, and librarians can play a role in helping students navigate that.”

Educator Esther Gottesman says that even her youngest students are capable of having hard conversations related to climate change. But the school librarian at Arts & Letters 305 United, a pre-K–8 school in the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, NY, is mindful not to scare them while providing tools to take action.

“Climate anxiety—climate panic—is real, and the greatest remedy is positive action towards making things better,” she says.

Gottesman, who began her career as a school garden teacher with Edible Schoolyard NYC, recently received a $5,000 sustainability grant from the NYC DOE that she used to purchase environmentally themed books for the library’s collection. Arts & Letters is creating a garden, which will become an extension of the library and its programming.

The library and garden provide a “totally different mode of learning for kids who aren’t always successful in the classroom and a creative space where structures are more inclusive,” Gottesman says.

For example, in partnership with the school's PTA sustainability committee, Gottesman has hosted library events tied to the NYC DOE’s Climate Action Days, four days in the school year that celebrate climate actions in schools. Each day has a theme: Energy; Waste; Health, Wellness, and Green Spaces; and Water. For Energy, Gottesman set up a station with examples of alternative energy sources, hosted a screening of the filmThe Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, and brought in a parent who works in alternative energy to speak with students. For Waste, Gottesman led a letter-writing campaign to encourage local politicians to include more funding for environmental resources in schools.

She also partners with grade-level teachers to extend classroom projects in the library. Third graders study birds, so Gottesman had students research at-risk species, like the piping plover, and conduct guided research on different bird conservation initiatives, such as using bird-safe glass in buildings.

|

From Left: Akilah Lewis, an NYC Department of Environmental Protection environmental educator, teaches P.S. 90 students about the water cycle; Tiffany Coulson Climate Emotions Wheel from the Climate Mental Health NetworkPhotos on this page courtesy of P.S. 90, Coney Island; Courtesy of Tiffany Coulson |

Strategies to stay hopeful

Laura Schifter is a senior fellow with the Aspen Institute’s Energy and Environment program and leads This Is Planet Ed, an initiative that combines education and climate action. There are two ways teachers can help students overcome their fears, she says.

“It’s critically important to, one, talk about the issue, because that validates children’s recognition that it’s a big issue and that adults recognize [that],” Schifter says. “And, two, teach them about why this is occurring and what’s driving it so you can connect directly to solutions.”

Imparting a solutions-driven approach that inspires action benefits young people beyond addressing on climate change, educators add.

“When you focus on students being good problem solvers, to read critically and take that information and come up with things they can do about it, you’re preparing them not only for this issue, but life skills to be ready to meet whatever the challenges are in 10 years when they are the adult,” says Elaine Makarevich, the New Jersey state lead for SubjectToClimate, an online hub of climate resources curated by teachers, scientists, and climate activists.

Carolyn McGrath has been a vocal activist in environmental education and sustainability for more than 25 years. In addition to being the visual arts teacher at Hopewell Valley Central High School in Pennington, NJ, McGrath has helped lead sustainability efforts for the entire school district. She also created the art climate curriculum for middle and high school students in the state through SubjectToClimate.

One of McGrath’s most impactful lessons has been the Climate Hero project, in which students are introduced to working artists making art about climate change. Then students learn about young people, not much older than them, who are involved in climate activism, including Autumn Peltier and Vanessa Nakate, and research and create a symbolic portrait of one of them.

McGrath says that lesson has been meaningful for students, especially because some activists have responded to student work over social media, and one, Ugandan environmental activist Nyombi Morris, visited the school to meet with students.

“It’s really important for students to have an understanding that these are real issues and they have the power to make an impact, and art making is a form of action,” McGrath says, adding that something like the Climate Hero project could be adapted for the school library or a maker space.

McGrath says librarians can also support student learning about climate change by helping them differentiate fact from fiction. A recent EdWeek poll found that 56 percent of 14- to 18-year-olds learn about climate change from social media. McGrath sees a similar majority in her own students.

“I think it’s good they are getting information from social media, because then it’s relevant and engaging. But if they don’t have any capacity for discernment, then you run into problems,” McGrath says. “Helping young people understand what they are listening to and how to evaluate the information, that’s really, really important. One of the most important skills we can teach kids.”

|

Marc Rolla (above, at right), P.S. 90 sustainability coordinator and science teacher, and a fellow educator tend the school beehive. |

Partnerships and art activism

In seaside Coney Island, Brooklyn, school librarian Laura Silver works hard to model sustainability and other ways students can make an impact. Silver was among the first New York City school librarians to receive certification through the Sustainable Libraries Initiative, whose stated goal is to help library leaders develop libraries that are more environmentally sound, socially equitable, and economically feasible, while strengthening community ties. The school has a robust, school-wide recycling program led by sustainability coordinator and science teacher Marc Rolla. Silver has also come up with other strategies for her library at P.S. 90: The Magnet School for Environmental Studies and Community Wellness, a Title I school, to further green solutions.

One has been finding new uses for outdated library books, which through the normal weeding process would have found their way to the garbage heap.

“We had probably 2,000 books, because the library had been out of use for about five years” when she arrived, Silver says. “We haven’t thrown one book in the trash.”

Silver coordinated the donation of some of those books to US-Africa Children’s Fellowship. Others went to the Little Free Library outside the school. The rest went to art projects. Silver used old picture books to decorate the library, and students made sculptures and collages out of other books.

This year, Silver is also partnering with the NYC DOE’s Service in Schools initiative, which promotes service-learning and community service. Students will learn more about the effects of climate change on Coney Island and create an action project, including signs, poems, and displays, for the community to learn more about what’s happening in its own backyard.

“Partnerships are so important,” Silver says. She recommends other school librarians interested in sustainability take advantage of them in their communities. “Lots of people doing this work would love to come to your classroom. You can partner an elementary school with a high school or environmental-ed students in higher ed. Most municipalities have people working in climate change. See who is active.”

Andrew Bauld is a freelance writer covering education.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!