Good Divorce Books: How to Identify Helpful Titles and Ones that Miss the Mark

Books need to leave room for a child’s feelings while normalizing divorce, encouraging questions, and teaching coping skills, experts say.

Search the internet for “books about divorce for kids,” and you’ll find lists with dozens of titles. There are plenty of books from reputable publishers, many with charming illustrations, but they often misfire. Their messages can affect a child’s image of their family and themselves, making adjustment and pride more difficult, not less.

Mallory Kennedy, 11, says that books and films about families touched by divorce tend to follow a familiar storyline: “You have a step-parent; you hate them. They’re so mean; they don’t like you.” But that’s not her experience. Fictional kids of divorce are often only children, but Mallory has four siblings. One of her own divorced moms lives a block and a half from where the other lives with Mallory’s “almost stepdad.” Her three parents divide and conquer weekend sporting events, and Mallory can visit them all after school.

|

Mallory Kennedy with her parents |

“It’s not sad,” she says.

Families like hers are increasingly common, with collaborative divorce and cooperative co-parenting on the rise. And decades of research confirm that divorce is not “basically a death sentence for the family,” says Christy Buchanan, professor of psychology at Wake Forest University and author of Adolescents After Divorce. After interviewing teens, Buchanan was “astounded at how well some of these families were handling it.”

But you wouldn’t know all that from many books on the market that address family structure. “They are all so negative,” says Elliot Kreloff, author and illustrator of the picture book Tuesday Is Daddy’s Day. Well, not all of them, fortunately.

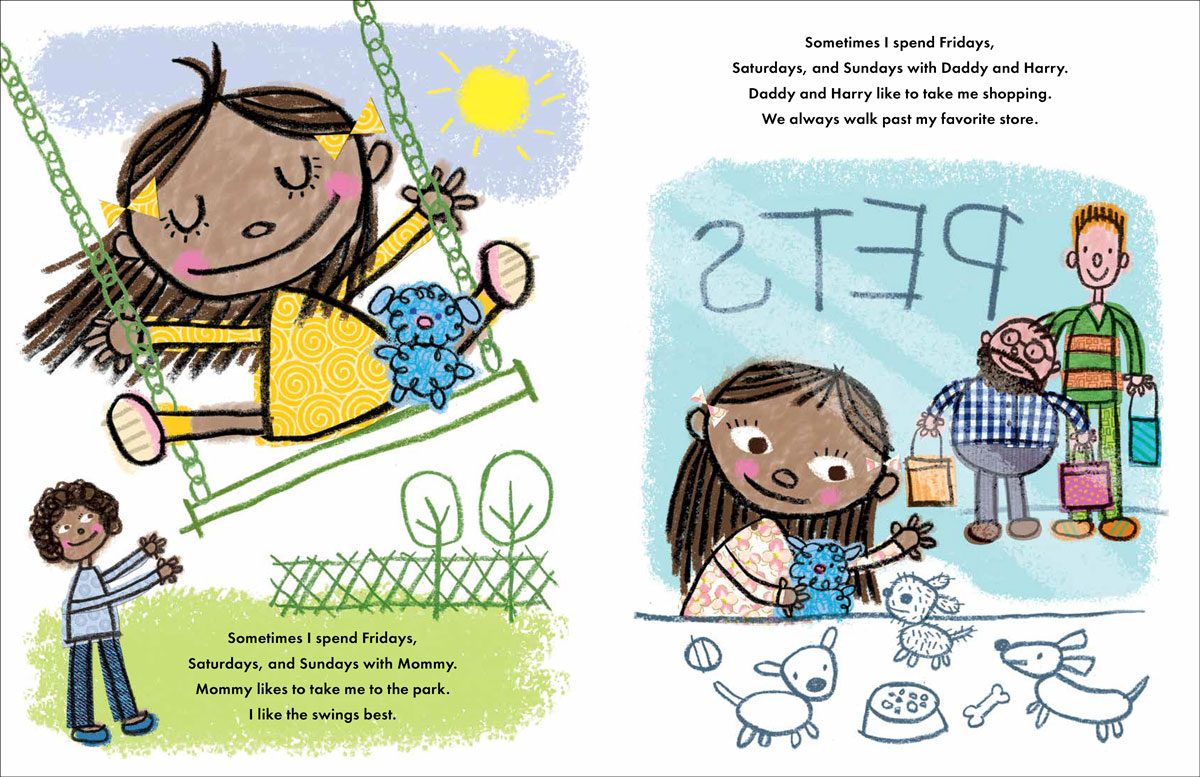

Kreloff’s book drew inspiration from his own family. His grinning female protagonist has two great beds. At Mommy’s house it’s big, while at Daddy and Harry’s house, it’s “snug.” Her calendar shows that she transitions between the two homes frequently. A picture of Mommy is displayed at Daddy’s home. But the protagonist is thrown when Mommy picks her up on a Tuesday, Daddy’s day. Soon the reader learns that her parents have been in cahoots. Daddy surprises her with a puppy as Mommy smiles on.

The parents in Living with Mom and Living with Dad by Melanie Walsh also co-parent effectively and positively. In this colorful lift-the-flap book, both parents’ homes and activities are enjoyable in different ways. The narrator knows, “If I miss my mom or my dad...talking to them on the phone makes me feel better.” In Always Mom, Forever Dad by Joanna Rowland, an illustration of one child in a diverse cast of young protagonists is accompanied by the words, “[H]e sings me a song she used to sing to me when I was a baby.”

|

|

Tuesday Is Daddy’s Day© 2021 by Elliot Kreloff. Reproduced with permission from Holiday House Publishing, Inc. |

Most books about divorce feature a white child (or an animal) whose heterosexual parents were once married. They either romanticize an affection-filled life before the split or describe a nuclear family marked by heated conflict and misery. Take Dinosaurs Divorce, in which the parents engage in a “violent, noisy battle” over the head of a child. In one illustration, a dinosaur in a dress stands near an overturned bottle of pills, kicking back a martini. After Dad moves out, the kids in these books rarely split their time 50-50. Distracted parents disparage each other.

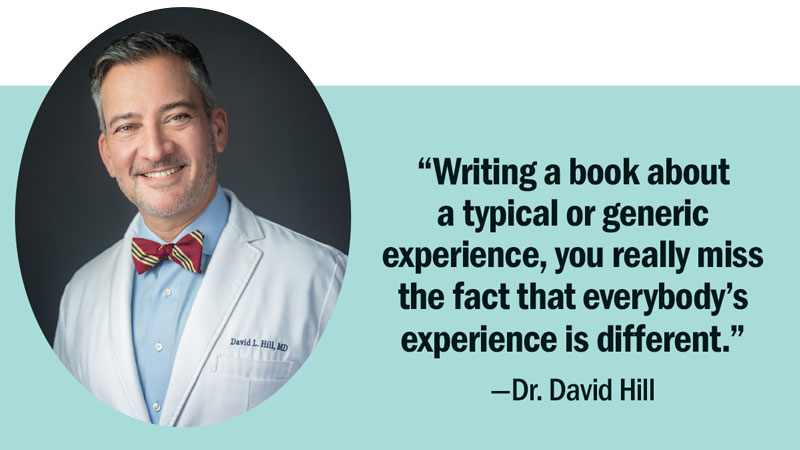

These things happen in real life, of course. It would be disingenuous not to acknowledge the worry and stress that kids experience during a change in family structure, no matter how well it’s handled, says David Hill, a pediatrician and coauthor of Co-parenting Through Separation and Divorce, published by the American Academy of Pediatrics. “Writing a book about a typical or generic experience, you really miss the fact that everybody’s experience is different,” Hill points out.

Children’s books need to leave room for a child’s upset feelings but also remind them “of all the good things that are happening in their lives, and how they can make things as good as possible,” Hill adds. In this way, books about family restructuring can be viewed similarly to new sibling titles. If you tell a child, through a story, that it’s going to be horrible, with the baby destroying their toys and taking all the attention, they will be primed for resentment. Messaging matters, Hill says.

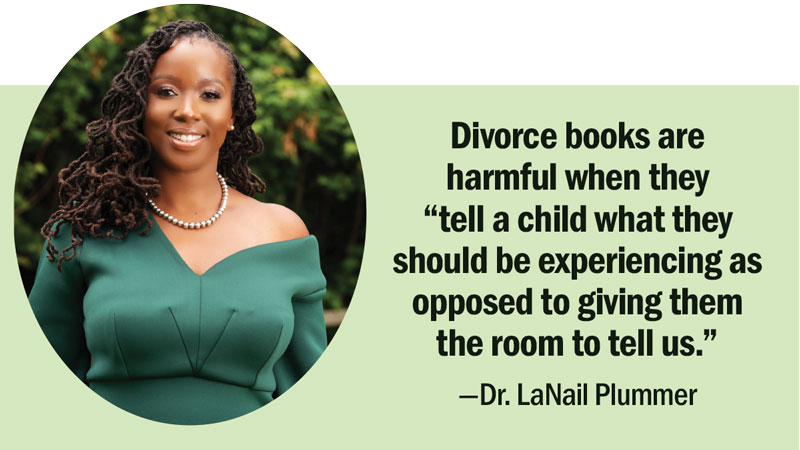

LaNail Plummer, CEO/Founder of Onyx Therapy Group and a lecturer at Johns Hopkins University, draws a different parallel: “We have fun books about moving houses, moving schools, or transitioning to another grade.” Their tone is upbeat despite addressing fear, longing, and nostalgia. “We should have something similar for children who are going through divorce.” Many divorce titles are “solemn and serious” because of emotions adults project on their children, adds Plummer.

LaNail Plummer, CEO/Founder of Onyx Therapy Group and a lecturer at Johns Hopkins University, draws a different parallel: “We have fun books about moving houses, moving schools, or transitioning to another grade.” Their tone is upbeat despite addressing fear, longing, and nostalgia. “We should have something similar for children who are going through divorce.” Many divorce titles are “solemn and serious” because of emotions adults project on their children, adds Plummer.

Titles that manage to effectively portray one thriving family in two homes “center on the child as the focal point, as opposed to the parents,” says Plummer. In Fred Stays with Me! by Nancy Coffelt and Tricia Tusa, a girl with a dog conveys the message that the child’s time is her own, not her parents’. “Excuse me!” the narrator says. “Fred doesn’t stay with either of you. Fred stays with ME!” Difficult things happen, like Fred stealing socks and barking at a poodle, but problem-solving makes it work.

That cheerfulness Plummer likes to see is on full display in Lou Caribou: Weekdays with Mom, Weekends with Dad by Marie-Sabine Roger and Nathalie Choux. Lou happily packs a suitcase and rides “the big bus and then the little train” to stay with Daddy Caribou. He feels “no need to worry about Mommy….[S]he will be with him even though she’s not with him.” A suitcase also takes center stage in the deliciously silly The Enormous Suitcase by Robert Munsch. The commiseration offered comes as caricature. Kelsey accepts traveling between two homes but insists on packing the following for a week at Dad’s house: clean clothes, a big box of colored pencils, five books, a unicorn picture right off her mom’s wall, a pillow, and her mom’s dog—which ends up snuggling with her dad’s cat, not attacking it. Kelsey’s dad says, “Isn’t it amazing how things can work out if you just try?” Kelsey brings her goldfish along the next time she switches homes. “But the cat ate the goldfish. Because it turns out that some things just do not work out, no matter how hard you try.” Munsch is said to have written the book after a fan requested one about a kid like her.

Both The Ring Bearer by Floyd Cooper and No Ordinary Family! by Ute Krause address apprehension around family restructuring while assuring kids there’s a place for everyone in a blended family. The latter indulges the fantasy of vanquishing stepsiblings, in this case, “prim and prissy little princes and princesses.” Plummer says that’s important: “Our early theorists like Piaget and Vygotsky and Erikson spoke about imaginative play and fantasy as a way of reconciliation and consolidation of thoughts.”

These experts offer three additional considerations when evaluating books about divorce for young children.

1) Prioritize normalization. Hill says for a child, “It’s easy to feel like ‘I’m the only person who has ever gone through this.’” Buchanan agrees, suggesting books that “make sure they understand that experiences are not necessarily the same for everyone,” but also that “you are not alone.” For older children, My Parents Are Divorced Too by the Ford family strikes that balance well. A Brand New Day by A.S. Chung portrays a child who experiences happy home switching. Lisa Kiang, a professor of psychology at Wake Forest University, says normalization is even more important for some marginalized groups: “Especially with an experience like divorce that may be taboo to talk about, not seeing familiar faces in books that are specifically geared toward the topic can be particularly problematic.”

1) Prioritize normalization. Hill says for a child, “It’s easy to feel like ‘I’m the only person who has ever gone through this.’” Buchanan agrees, suggesting books that “make sure they understand that experiences are not necessarily the same for everyone,” but also that “you are not alone.” For older children, My Parents Are Divorced Too by the Ford family strikes that balance well. A Brand New Day by A.S. Chung portrays a child who experiences happy home switching. Lisa Kiang, a professor of psychology at Wake Forest University, says normalization is even more important for some marginalized groups: “Especially with an experience like divorce that may be taboo to talk about, not seeing familiar faces in books that are specifically geared toward the topic can be particularly problematic.”

2) Encourage questions. Plummer says divorce books are harmful when they “tell a child what they should be experiencing as opposed to giving them the room to tell us.” Adults can read a book like It’s Not Your Fault, Koko Bear by Vicki Lansky with a child and pause to ask, “Have you ever felt like that?” Stories such as Standing on My Own Two Feet by Tamara Schmitz, where both parents attend the protagonist’s events, give children permission to ask questions. Buchanan envisions an adult reader saying, “Some people have separate birthday parties, and some people have the birthday party together. What might you like? Is there anything that worries you about that?”

3) Teach coping skills. Traditional divorce books often try to empower kids by telling them what their parents shouldn’t be doing, like using them as a messenger, and suggest they push back. But “it’s a fine line to walk to encourage them to vocalize their feelings, and yet not give them an increased burden,” says Hill. They shouldn’t feel responsible for managing their parents. Instead, Hill recommends books that give kids answers to the questions: “What do you do when you’re upset or sad? Who do you talk to?” That approach is also helpful for kids like Mallory who says there are tough parts about living in two houses, though overall, “It’s actually more love.” Titles like Glad Monster, Sad Monster by Ed Emberley and Anne Miranda aren’t about family structure but give kids the emotional literacy necessary to navigate its complexities. In addition to books that facilitate conflict resolution, communication, and problem-solving, Plummer recommends those that address grief, especially the idea that humans can mourn something they don’t want back. “We experience grief when we graduate from college too,” she says.

Before handing any book about family structure to a child, Hill says, “Flip through and see if this is a message that resonates.” For kids who are already struggling, a book that discusses or illustrates a rocky “before” and “during” may make sense. American Girl’s A Smart Girl’s Guide to Her Parents’ Divorce contains important messaging around common fears, but the book also has flaws, including the assumption that the father left the mother. Still, kids can handle almost any mixed bag when coached to take a critical lens: “What about this book feels right to you and what doesn’t match up with your experience?”

As Plummer says, the key in sorting through these books is realizing, “We have to be able to meet them where they are. Not where their parents are. Not where the traditional narrative is. Where the kids are.”

Gail Cornwall is a former teacher and recovering lawyer who now works as a mother and freelance writer in San Francisco.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!