Verse Novelists Forge a Unique Connection with Young Readers

Middle grade and YA authors including Joy McCullough, Reem Faruqi, and others discuss the power of verse to address emotional topics and craft innovative narratives.

|

|

Kip Wilson in BerlinPhoto courtesy of Kip Wilson |

Author Kip Wilson felt something click when, after drafting nine unpublished books in prose, she tried verse. “It was sort of like falling in love. It just felt right,” says Wilson. Her first YA verse book, White Rose, based on the story of Sophie Scholl and the resistance movement against Hitler, was published in 2019; her second, The Most Dazzling Girl in Berlin, about finding queer community in 1932 Germany, came out last month.

Dean Atta had a similar “light bulb moment” about verse when his editor recommended he read Elizabeth Acevedo’s The Poet X. “It reminded me of when I was 16 and I first saw a spoken-word poetry performance and thought ‘I want to do that!’” Michael, the main character in Atta’s YA verse novel The Black Flamingo, writes and performs poetry as he explores his identity through drag.

Novels in verse can be a revelation to readers. Connected poems tell the whole story while also playing with format. Often character-driven and addressing emotional topics, these books invite readers to savor language while delving into moving and innovative narratives.

The rhythm of a verse novel creates a compelling way of experiencing the story. Readers often slow down and linger on the words and images in front of them instead of racing toward the next plot revelation. Verse novels may also engage readers who shy away from prose novels.

[Also read: "10 Books Showcasing the Power, Emotion, and Creativity of Verse"]

Authors are drawn to write in verse for many reasons. Sometimes it’s just a stroke of inspiration. Other times, the content leads to the choice, as was the case with Reem Faruqi, author of the middle grade novel Unsettled, about a young Muslim girl’s immigration from Pakistan to the United States. “Verse felt fitting because when you reluctantly move continents, you feel a little broken at first—sort of like how my character Nurah felt when she first moved,” says Faruqi. “The broken nature of the lines in the novel of verse reflects Nurah’s experience.”

In Rajani LaRocca’s middle grade verse novel Red, White, and Whole, protagonist Reha is an Indian American girl dealing with the grief of her mother’s leukemia diagnosis. The intensity of Reha’s feelings made verse seem natural to LaRocca. “I knew Reha’s story would be very internal and emotional, so I thought that verse would be the right format,” she says.

Chris Baron’s middle grade verse novels All of Me and The Magical Imperfect explore themes that are personal to him, including “body image, chronic illness, immigration, Jewishness, [and] intergenerational relationships.” Poetry helped Baron navigate and understand challenges he faced growing up, including bullying about his body and anti-Semitism, he says. “Early on, poets like Maurice Sendak, Gwendolyn Brooks, Shel Silverstein, A.A. Milne, and so many others gave me an honest, whimsical hope.” He adds that the musicality of novels in verse are “like a first language—a place of exploration, but also a safe harbor.”

Connecting with a voice

Verse novels are voice-driven, often intimate feeling, and seem uniquely suited to tackling complex or emotional subjects. Baron sees power in the very format itself. “The structure of verse creates an intimacy with a reader that allows them to hear the tone and cadence of a character’s voice. This can create even stronger connections for readers.”

Joy McCullough gravitated to verse for her historical YA works: We Are the Ashes, We Are the Fire is about a rage-fueled girl who becomes obsessed with a 15th-century French noblewoman turned knight, Marguerite de Bressieux; Blood Water Paint is an exploration of the life of Artemisia Gentileschi, a talented woman painter in 1600s Rome.

“For historical YA about difficult topics, verse allows me to strip away everything that distracts by making the events feel distant and write to the heart of the matter,” says McCullough.

Author K.A. Holt finds that “verse allows for a pretty intense partnership with your reader.” Holt’s many verse novels include Redwood and Ponytail, a middle grade book about two girls’ growing attraction to each other. The story is told in a dual narrative with a Greek chorus of student voices.

Her poetry prioritizes characters’ emotions, with fewer descriptive details than a prose novel may offer. Holt believes readers fill in those missing details, perhaps identifying with the characters as they flesh out the story. “And when those personal commonalities meld with the universal emotions I’m expressing in the verse, then boom, the readers and I are now writing the story together.”

Working the white space

Many authors note the work of the white space on the page, providing places to stop and rest.

“Verse uses fewer words and leaves more space on the page, so readers have more space to process what happens emotionally,” says LaRocca. “Because of this, difficult or heavy topics can be touched upon without exhausting the reader.”

Faruqi agrees. “It gives the reader time to reflect,” she says. “I found the white space soothing, and the words could sing. Without the extra text, my character Nurah’s voice shimmered and became more powerful.”

Wilson notes, “White space helps balance the heaviness of those words,” while Baron sees the white space as a place to take a breath. “Young readers see and feel so much, but they aren’t always good at talking about what they experience. Novels in verse can help articulate, and hopefully help represent, our complex and emotional subjects.”

The format ensures that only the most vital words make it to the page. There is power and purpose in every aspect of a novel in verse, from the choice of words to line breaks to white space.

“Verse is story in its most concentrated form,” says LaRocca. “I tend to write lyrically, but with verse, I use imagery, sensory detail, and metaphor to build layers of meaning.”

Atta says, “With verse you can control the pace of reading in a much more obvious way. You can instruct a reader to slow down, speed up, pause, or stop. You have regular punctuation at your disposal, but you also have line breaks, line spaces, and white space to give extra prominence and power to individual lines or words of your choosing.”

Candice Iloh’s verse novel Every Body Looking follows Ada, who leaves behind her controlling Nigerian father in Chicago to attend a historically Black college in Washington, DC, and begins to discover her authentic self. “Poetry inherently feels more powerful to me because it is the first language I learned to speak as an artist,” says Iloh. “I know how to wield it, most times, better than anything else.”

|

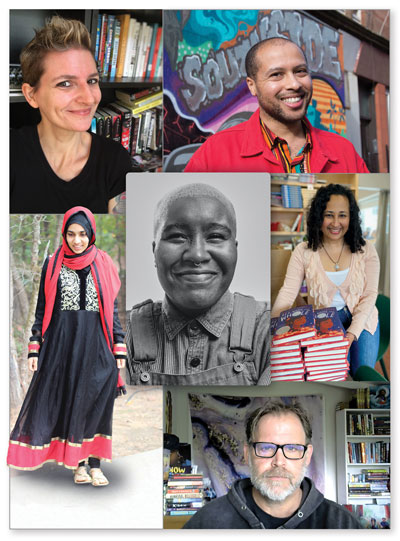

Clockwise from top left: K.A. Holt, Dean Atta, Rajani LaRocca, Chris Baron, Reem Faruqi. Center: Candice IlohPhotos courtesy of the authors. Dean Atta photo by Thomas Sammut; Reem Faruqi photo by Zaheer Faruqi |

Freedom to play

Authors also love the ability to experiment with verse. “Novels in verse provide wonderful opportunities to play with form and shape on the page—this enhances meaning and enjoyment, especially for young readers,” says LaRocca.

McCullough adds, “It’s not that you can’t play with structure and time in prose, but verse is really built for experimentation. There are truly no rules, which can be daunting, but also incredibly freeing.”

However carefully an author crafts a verse novel, the reader will always have their own takeaway.

“I can attempt to use syllables, layout, white space, and punctuation—or lack thereof—to control pacing and rhythm, even when a reader holds their breath or when they exhale. But ultimately? I have to trust my reader to use the pathway I’ve laid out for them, so that they can find their own meaning,” says Holt.

Iloh feels that the verse structure makes readers focus on what matters most. “There is no word on the page that isn’t doing work. And so, you have this unique opportunity to manipulate the experience in a way that leaves only what matters as the focus,” they say.

Still, the limitations of the form can present challenges. “It can be harder to show what’s going on in the story outside of the main character’s narrow perspective,” Wilson notes. “Some verse novelists get around this by writing dual or multiple points of view.”

One challenge for Atta was condensing his story. “Because verse takes up more space than the equivalent number of words in prose, novels in verse tend to have a fairly low word count. I wrote way more story for The Black Flamingo than made it into the published book. But I feel joy after trimming back subplots and secondary characters to reveal the most distilled version of the story I’ve been trying to tell.”

Once authors write a novel in verse, they tend to continue to use the format. Faruqi’s latest middle grade book, Golden Girl, about a Pakistani American girl trying to figure out how to reunite her family after her father is arrested for a crime he didn’t commit, is also in verse, as is LaRocca’s 2023 middle grade novel, Switch, about twin sisters. The recent YA title Great or Nothing, a coauthored Little Women retelling in verse, features authors McCullough, Tess Sharpe, Caroline Tung Richmond, and Jessica Spotswood each writing one sister’s point of view, with McCullough taking Beth’s voice.

Wilson’s 2023 work One Last Shot is a historical YA novel told in verse about Gerda Taro, the first female photojournalist killed in battle during the Spanish Civil War. Salt the Water, Iloh’s second verse novel, also publishes next year. In it, a nonbinary high schooler from the Bronx hopes to move out west after graduation and live off the grid. Holt’s upcoming This Is Not a Drill, a middle grade novel about a lockdown, is told in text messages and message board comments. Atta’s spring 2022 YA novel in verse, Only on the Weekends, is a romantic coming-of-age story.

While Baron’s two forthcoming middle grade books, The Gray World (2023) and Forest Heart (2024), are not in verse, he believes that “the joy and lyrical soul of verse will be there.”

“Poetry speaks to the heart,” he says. “We see with more than just our eyes, and the music of poetry helps to make words sing directly to us.”

10 Books Showcasing the Power, Emotion, and Creativity of Verse

Elementary/Middle Grade

The Deepest Breath. Meg Grehan. Clarion/HMH. 2021.

Gr 3-7–Irish 11-year-old Stevie copes with anxiety, which manifests as stressful dreams, stomach aches, a “noisy head,” and lots of overthinking. She suspects she knows what’s behind the “fizzy feeling” she gets around her friend Chloe but needs to know more to be sure. A gorgeous, heartfelt, and affirming exploration of identity.

The One Thing You'd Save. Linda Sue Park, illus. by Robert Sae-Heng. Clarion/HMH. 2021.

Gr 3-7–Inspired by sijo, a Korean traditional syllabic poetic form, students in a class considers what one object they would save if their homes were on fire. With ample, gray-toned illustration, this short volume is a thoughtful and empathetic reflection on what we value.

Rez Dogs. Joseph Bruchac. Dial/Penguin. 2021.

Gr 3-8–Eighth grade Penacook Malian’s pandemic lockdown brings stronger connections to family, culture, and community when a brief visit with her grandparents on the reservation turns into an extended stay. Her grandparents share moving stories about both family and history, which Malian shares with her classmates during distance learning.

Samira Surfs. By Rukhsanna Guidroz, illus. by Fahmida Azim. Kokila/Penguin. 2021.

Gr 4-8–Eleven-year-old Samira and her family flee Burma for Bangladesh in 2012, and Samira longs to attend school rather than just work to help support her family. She picks up surfing in hopes of winning a cash prize and makes new friends as she learns to overcome her fear of the water. A layered look at a young Rohingya refugee’s trauma and dreams.

We Belong. By Cookie Hiponia Everman, illus. by Abigail Dela Cruz. Dial/Penguin. 2021.

Gr 4 Up–Half-white, half- Pilipino sisters Stella and Luna listen as their mother intertwines the stories of a Tagalog myth of moon goddess Mayari and her own family’s escape from the Philippines during Ferdinand Marcos’ presidency. A moving tale of belonging and home. A Tagalong glossary is included.

Young Adult

The Seventh Raven. By David Elliott, illus. by Rovina Cai. Clarion. 2021.

Gr 6 Up–A retelling of the Grimms’ “The Seven Ravens” tale. Fifteen-year-old April sets out to find her seven brothers, who were cursed and transformed into ravens by their father upon April’s birth. But the youngest son, Robyn, loves the air and flight, and may not want rescuing. Told from multiple points of view and in various poetic forms, including rondeau, Onegin stanza, the Welsh Cyhydedd Naw Ban, and couplets.

Me (Moth). Amber McBride. Feiwel & Friends. 2021.

Gr 8 Up–After losing her family in a car accident, Moth, who is Black, grapples with heartbreak, guilt, and trauma. A new friendship with Navajo boy Sani and a road trip provides connection and comfort, as well as a shocking revelation. A stunning and emotional story of being seen and letting go.

Your Heart, My Sky: Love in a Time of Hunger. Margarita Engle. Atheneum. 2021.

Gr 8 Up–Liana, 14, and Amado, 15, meet in 1991 in Cuba, both looking for food in a time of starvation, defying their obligation to “volunteer” for farm labor, and brought together by a stray dog, hope, and love. A profound and gripping look at scarcity, famine, resilience, and dreams.

When We Make It. Elisabet Velasquez. Dial/Penguin Young Readers Group. 2021.

Gr 8 Up–In this narrative set in the 1990s, eighth grade Nuyorican Sarai lives in Brooklyn and works to figure out where she fits as she deals with poverty, her mother’s mental illness, inequity, colorism, identity, and more. A painful, hopeful, and beautiful read about survival and what it means to “make it.”

Nothing Burns as Bright as You. Ashley Woodfolk. Versify. 2022.

Gr 10 Up–A nameless narrator takes readers back 867 days before a fire, recounting the complicated and all-consuming relationship, full of love and volatility, of two Black girls. Non-linear timelines, truth, and lies jumble together in this affecting look at queer love, toxic relationships, reckless hearts, and wanting more.

Amanda MacGregor blogs at “Teen Librarian Toolbox.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!