Teacher Appreciation Week: Authors Share Memories Of Educators Who Made an Impact

Daniel Bernstrom, Carole Boston Weatherford, Cynthia Leitich Smith, Kekla Magoon, Scott Reintgen, and others share stories about educators who played an important role in their lives.

Is there a teacher that looms large in your memory? Someone who encouraged you, saw something in you that you didn’t recognize in yourself? Someone who showed you kindness when you most needed it? In celebration of Teacher Appreciation Week, May 6–10, School Library Journal reached out to authors and illustrators to share memories of a teacher who made a difference, perhaps impacting the trajectory of their careers. Here’s what they had to say.

...

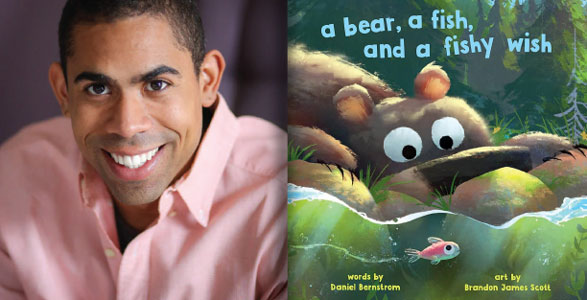

From Daniel Bernstrom, author of A Bear, a Bee, and a Honey Tree (2022, Astra), and the forthcoming A Bear, a Fish, and a Fishy Wish (May 2024, Astra)

The new teacher, the principal's wife no less, stepped into our 11th grade English classroom—a whirlwind of enigma. She was nothing like the English teachers who diagrammed sentences that we had always known. I mean, she was easily distractible and a bit...different.

On that fateful first day, she leaned against the chalkboard, her eyes twinkling with mischief. “If I collapse during class,” she declared, “it's probably because my brain tumor has finally killed me.” We exchanged glances, unsure whether to gasp or giggle. But she was serious. Deadly serious. A tumor, nestled at the base of her brain, clung to a vital life-giving junction like a hidden landmine.

And so we waited. Not for the bell to ring, but for Mrs. Beach to drop dead. In the meantime, she taught us about thesis statements, essay structure, and the art of crafting hooks that captured readers. But her lessons transcended mere subject-verb-object. She taught us how to infuse our writing with heart and feeling. She knew that inside each student was a universe of ideas and unique experiences.

Her life was no exception, for it seemed woven from myth and legend. Once, she cheated death on a moonlit beach. Another time, she stumbled upon an artesian well in a sun-drenched prairie—a hidden oasis where she bottled virgin water.

Her appearance was equally enchanting. Gaudy rings gleamed upon spindly fingers, and sparkling necklaces danced against her elaborate blouses. Each piece held a story—a gift from a past admirer, a token of love or heartache. She was a heartbreaker, a sorceress of memories. So it was that English class became a portal to other worlds.

Whenever we were bored, then there was the brain tumor. Our secret weapon. We'd stop her mid-lecture and ask her about death. Mrs. Beach would stop and perch on her desk, her gaze drifting to some far-off, painful place. Then she'd share another chapter of her battle with cancer: the hospital visits, the shunt drilled into her skull. And I listened, hoping her stories would weave for me a magical map out of my fragile existence into the fearless world she inhabited.

So it was that Mrs. Beach granted me the magical spell to help me take my grammar-laden sentences and make them dance, weep, or soar! Her classroom became a sanctuary where weakness was worshiped. In that sanctuary, I learned she believed in me. Mrs. Beach's belief in my potential was the fertile soil in which my writing ability took root.

Mrs. Beach didn't drop dead in that classroom, but her impact on my life is a testament—a testament to the power of a teacher who took weakness and made it wonderful. She pressed a seed into the soft soil of my soul. Today, that seed has bloomed. It is still blooming, and each flower I create is my feverish attempt to tell a story as remarkable as the ones she once told me in 11th grade English.

...

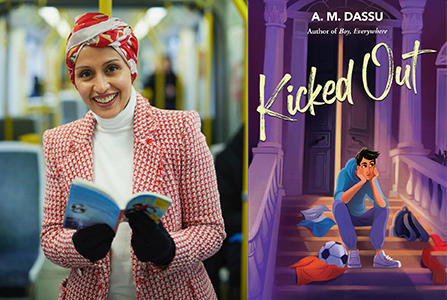

From A. M. Dassu, author of Boy, Everywhere (2020, Lee & Low Books), Fight Back (2022, Lee & Low Books), and Kicked Out (2024, Lee & Low Books)

Teachers hold a dear place in my heart. From my first, my mother, to my most recent who delivered a creative writing workshop I attended.

One teacher who always comes to mind when I think about books and school is Mrs. Palfrey. She was my high school English teacher and I paid homage to her in my debut novel Boy, Everywhere. In fact, she inspired all of the English-lesson scenes I’ve written in my books so far. Mrs. Palfrey—way back when there was no such thing as diverse books, let alone in children’s literature—introduced our class to Mildred Taylor’s Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry. She had us read it out loud, and I recall everyone in my class groaning whenever I was asked to read, because I couldn’t help but read out in an American accent from the deep South! The voice in that book is so powerful! We discussed racism, land ownership, community, and other issues that arise in the book. It changed the way I saw novels and how a strong voice can really impact a reader’s experience. It made me see how one can stand up to injustice with dignity.

Mrs. Palfrey was unassuming, quietly supportive, and a teacher who clearly made more of an impact on me than she realized. She introduced me to worlds and genres I may never have known. She made me feel safe and valued. I wish I could find her and tell her.

When my children are at school, they spend a good chunk of their day with their teachers. I’m no longer the first to know what they do or say, and I am grateful for every educator who tirelessly tries to imbue learning, growth, and critical thinking in them.

To every teacher out there, thank you. You touch our lives in many ways and we’re all better off thanks to you.

...

From Anna Lapera, the author of Mani Semilla Finds Her Quetzal Voice (2024, Levine Querido)

Mr. Savett taught my 10th grade creative writing class. That probably sounds cliché: a writer’s most impactful teacher was a creative writing teacher? Maybe, but for reasons unrelated, I didn’t write for decades after that (well, OK, almost two decades). But that’s not the point. The point is, Mr. Savett loved Bob Dylan. And I loved Bob Dylan. He dissected Dylan’s songs on an overhead projector with a lamp that buzzed and radiated heat that could melt the early-2000s candy choker necklace off your neck if you sat in the front row (and I always sat in the front row). I later learned that this was called workshopping a poem. I grew to love the tedious task of analyzing every word and line break. Mr. Savett would ask questions about the poems. When no one answered right away, he didn’t probe or re-word. He waited. He gave us time, and space. I learned that two people could look at the same poem, and interpret it differently in equally valid ways. Poetry quickly became my favorite thing to read. I learned to read profoundly and in-between lines. I learned how to listen: to words, to blank spaces, to classmates. I also learned to be kind. When I said something insensitive, Mr. Savett sat with me and helped me think through an apology to my classmate. And when I lost a sibling that same year, he shared a proverb about the human capacity to overcome. From Mr. Savett I learned that, for everything, there is a poem.

...

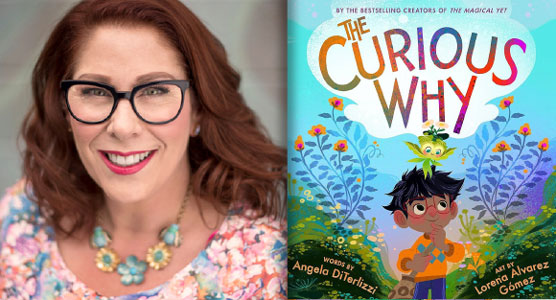

From Angela DiTerlizzi, author of The Magical Yet (2020, Little Brown) and The Curious Why (May 2024, Little Brown)

My 11th grade English teacher, Ms. Barbara Walters (not to be confused with the Barbara Walters), wrote an assignment on the chalkboard: Write a poem. Read it aloud. Due in one week.

Ms. Walters often spoke of “challenging yourself.” For this challenge, she suggested we focus on something that inspired us.

I wasn’t inspired. I wasn’t a poet. I was the class clown. Poetry was written by men with long beards pondering ponds, and women in petticoats pining away for lost loves, not 17-year-olds who sold hair accessories and hosiery at the mall.

On Sunday afternoon, after a week of procrastination, I could avoid the task no longer. I had to write something. Something inspired. Sitting in my living room, my eyes came to rest on a vase of red roses sitting atop our cocktail table. “Flowers? Really?,” I thought to myself. Flowers were quite possibly the tritest thing I could ever write about, but I didn’t care. I was desperate.

I contemplated the beauty of the blooms, their velvety crimson petals and threatening thorns. My words began to flow. I placed my earnest attempt in a folder and on the cover I inscribed the title “Ode to a Rose.”

I found out the next day that most kids wrote about love, friendship, and feelings. One of the football players wrote a haiku about his car.

“Ang, you’re up!” Ms. Walters’s voice snapped me out of my seat. I began to read. My poem’s title garnered snickers, but the real verdict would be delivered by Ms. Walters. She returned our folders the next day, but without a glance, she continued past me. My mind filled with terror as she sat back at her desk, pointed a finger, and motioned for me to approach. She slid a folder toward me. “Open it.”

My eyes darted from the paper back to Ms. Walters. A+? Surely this was some sort of mistake.

“Your poem is wonderful, and you’re a natural, Ang. You should keep writing,” she said. I was stunned.

But I shouldn’t have been. Ms. Walters was doing what she did every day: challenging her students and teaching us—though not about English, poetry, or writing this time. She was teaching me about myself. She saw something that I had yet to see, and her words still resonate with me. Now, more than 30 years later, whenever I question my work, skills, or abilities, I hear her voice say, “Keep writing.”

At 17, I was reluctantly inspired to write a poem about a rose. At 50, I’m genuinely inspired to write about a teacher who made a difference in my life.

Thank you, Ms. Walters. This one is an ode to you.

...

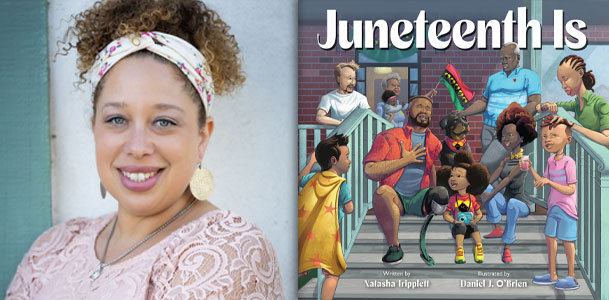

From Natasha Tripplett, author of Juneteenth Is (2024, Chronicle Books) and other titles

I have always loved poetry and stringing together words with similar sounds. As a child, I used to imagine myself as a character in the stories I read. Books were a way to escape the big things in life that I could not make sense of. They took me out of my reality, fueled my propensity towards procrastination, and gifted me with a whimsical world of wonder. This is what I carried with me as I walked into my eighth grade English class. I had just moved to the United States, and I felt vulnerable and anxious. I was surrounded by a sea of white classmates and a hurricane of jumbled thoughts swirled in my head. I knew I didn’t belong.

Mrs. Vander Well began teaching us how to diagram sentences. “It all starts with a subject and a verb—a person and an action,” she told us. “Everything after that builds layers in structured patterns.”

The class groaned as she explained adverbs, adjectives, prepositional phrases, and indirect and direct objects. I felt like this framework of words and phrases calmed the waves of my anxiety. It made sense. Every feeling and word had a place. Maybe I wasn’t a fish-out-of-water. Maybe, just maybe, I could find my place through writing.

That year, Mrs. Vander Well encouraged me to write. She was honest when my papers were lazy, and I needed to add more of “me” into them. She both challenged and buoyed me. It was the life jacket that I needed to dive into writing words with meaning. Because of Mrs. Vander Well, I fell in love with grammar. She taught me the importance of knowing the rules so I can break them with purpose.

Thank you, Mrs. Vander Well for teaching me to “sea” the world through words.

...

|

From Cynthia Leitich Smith, author of Harvest House (2023, Candlewick), and co-author of Blue Stars: Mission One: The Vice Principal Problem: A Graphic Novel (2024, Candlewick)

In sixth grade, Mr. Rideout launched my writing career. I had my own column, “Dear Gabby,” in our classroom newsletter at Rosehill Elementary in northeast Kansas.

I provided advice to the troubled and lovelorn. Believe me, sixth grade was rife with both. I addressed high drama—conflicts between cliques, struggles on the sports field, and the day-to-day challenges of home life. Anything from best-friend breakups to the death of a hamster to embarrassment over braces fell under my purview. I took the responsibility seriously and put a lot of thought into my answers.

Mine was the only column in the newsletter. Why me? I was awkward. Tall—at least a foot taller than my peers. (They kept growing. I didn’t.) I was shy and bullied for my garage sale and discount store clothes. I didn’t know a single other Indigenous kid at school.

But from the written homework I handed in, Mr. Rideout heard my voice and gave me an opportunity to share it. “Dear Gabby” was blessedly anonymous, which meant I’d been provided a safe space to build my confidence. I went on to become editor of my junior high and high school newspapers. I majored in journalism with a concentration in English, and of course, I write books for young readers today. Granted, I already had a love of language, story, and books—but it was Mr. Rideout who first noticed the pen in my hand and said, “You can do this.”

[READ: Fighting for Libraries, On and Off the Page: A Conversation Between the Co-Authors of the “Blue Stars” Series]

...

|

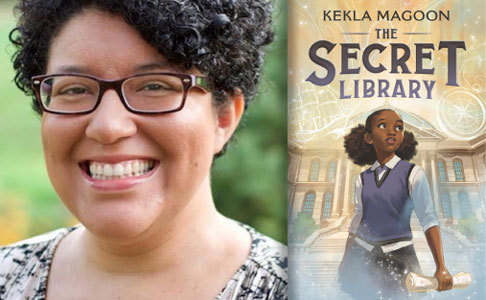

From Kekla Magoon co-author of Blue Stars: Mission One: The Vice Principal Problem: A Graphic Novel, and author of The Secret Library (both May 2024, Candlewick)

When I was a child, I never aspired to be a writer. It didn’t even occur to me. I loved reading and stories above all, but the idea that my voice could join the chorus of authors I cherished on my bookshelf? That possibility was nowhere on my radar.

My junior year in college, Professor Pam Harkins assigned us to write various personal essays for African American Literature class. She gave me an A on my essay about a racialized early childhood experience. She scrawled in the margins: “Keep writing! These narratives are important.” Her use of a fancy word like “narratives” to describe my story felt…powerful. I found my way to writing professionally just a few years later. Holding onto her encouraging words helped me stay strong through all the ups and downs and rejections of my first years in publishing. I hold onto them still.

Professor Harkins is the type of teacher who believes in all her students’ ability to achieve. Many other Black students, in particular, at this predominantly white university benefited from her close attention and encouragement. When we chat on the phone to catch up (sometimes for hours—ever the teacher, Professor Harkins always has a lot to say), she invariably reports proudly on other past students and their accomplishments. (“Did you know so-and-so was nominated as a federal judge?”) She keeps up with dozens of us, and it always brings me a smile to see her post an article mentioning my work, or celebrating a former classmate’s achievements, and to know that she is still cheering us all on.

...

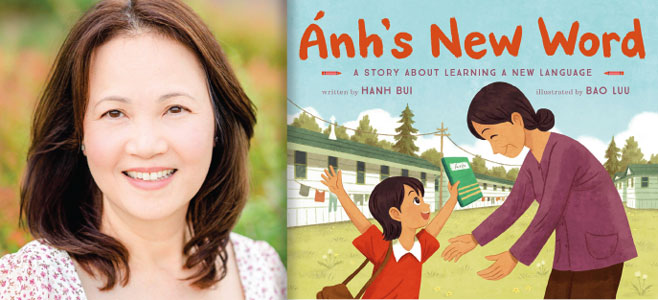

From Hanh Bui author of The Yellow Áo Dài (2023, Macmillan) and the forthcoming Ánh's New Word (2024, Macmillan)

In 1975, my family and I left war-torn Vietnam in hopes of being granted asylum and a new beginning in the United States. After a harrowing journey at sea and weeks at a resettlement camp on the island of Guam, we settled at Fort Indiantown Gap in Pennsylvania, an army base that served as temporary housing for displaced Vietnamese refugees.

My life was forever changed when I met Miss Marilou, my first American teacher, at “The Gap.” I was a shy, reluctant child who had selective mutism due to the trauma of war and loss of home. I didn’t utter a word during my first week of school at the refugee camp. I wanted to join in along with the other kids, but my fears kept me silent.

Miss Marilou’s gentle disposition and warm voice comforted me and created a safe space for me to grow in courage and words. Under her compassionate care, I learned to speak a new language. I fell in love with it because it allowed me to connect with her and experience a sense of belonging. Miss Marilou was my first ally when I was most vulnerable. Kindness can change the trajectory of a child’s life.

On our last day together, Miss Marilou gifted me a wallet-sized photo of herself. She wrote a sweet message on the back and signed it with her full name. In 2021, my husband found my first teacher by researching the name on the photo. I am beyond grateful to be able to express my gratitude to her in our shared language.

My book, Ánh’s New Word is an expression of my gratitude to teachers and a love letter to children. Happy Teacher Appreciation Week from a newcomer who became a dreamer because of a kind teacher.

...

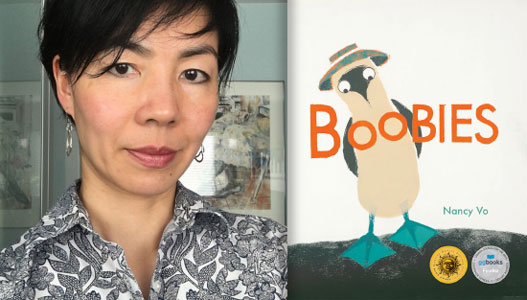

Photo by Nancy Vo |

From Nancy Vo, author/illustrator of The Outlaw (2018, Groundwood Books), Boobies (2022, Groundwood Books), and the forthcoming The Runaway (August 2024, Groundwood Books)

Writing about someone 45 years later is bound to be a bit unreliable, our memories being the cleverest of shapeshifters. However, the important things that I remember about my fifth grade teacher have stayed clear and true for me.

Our whole class loved Mr. Tritter. The class was also notorious for having a couple of the toughest kids who even frightened grade sixers. Yet, in the presence of this man, they parked their tempers. He saw each of us as something better than we thought ourselves to be, so we behaved accordingly.

Mr. Tritter also showed us a way to be better together. We were an east side school, but he decided that we would create a play and perform it in the iconic Calgary Alberta Jubilee Auditorium!

In the middle of rehearsing, we hit a rough patch. Rather than brushing it aside, our teacher typed a letter, made copies, and handed them out at the start of the next class. He was asking us to be accountable and trusting us to resolve this tricky situation. I recall tears, but I also recall the catharsis that came at the end. I kept a copy of that letter. Thank you for showing us the best version of ourselves in grade five, Mr Tritter.

...

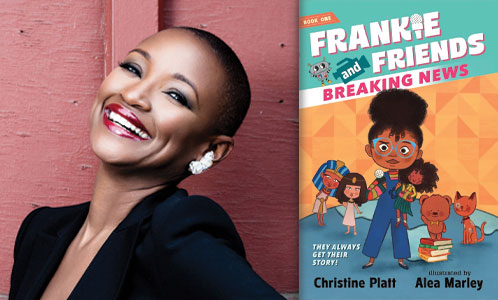

Photo by Norman E. Jones |

From Christine Platt, author of Frankie and Friends: Breaking News (2023) and Frankie and Friends: The Big Protest (2024, Walker Books US/a division of Candlewick Press)

As a child, I was always an avid reader. But I’ll never forget the day I fell in love with words and the power of language. And in the most unexpected way—through an insult.

I was a seventh grade student at Conniston Middle School in my hometown of West Palm Beach, FL. The class period was English, and my teacher was a petite African American woman named Mrs. White. Unlike other educators who allowed for a little flexibility in students’ demeanor and attentiveness for the first five minutes of class, Mrs. White was no-nonsense when it came to us settling in. Still, that didn’t mean that someone didn’t test her patience every now and then. And one day, it was my turn to learn one of her valuable lessons the hard way.

When the school bell rang, Mrs. White turned off the lights before walking to the front of the classroom where she flipped up the switch for the overhead projector light (I know, I know. I’m totally dating myself here!). I watched as she carefully positioned the transparent sheet that enlarged the day’s lesson on the screen at the front of the classroom. Believing myself somewhat cloaked and protected in the dimly lit room, I said something slick—what I said, I still can’t recall. But I’ll never forget her response:

“Don’t be crass, Christine.”

Crass? What in the world did that mean?

“What is ‘crass’?” I asked.

“Well, if you’d stop interrupting class so I can teach today’s vocabulary lesson, you and everyone else will find out.”

The joke was on me when Mrs. White defined the word “crass.” Of course, “crass” became one of my favorite words.

I had many conversations with Mrs. White after that English lesson. About how cool it was that there were so many different words that had the same meaning (“Adjectives,” Mrs. White taught me.) And that it was quite possible to use those words to share messages and information (“Storytelling,” Mrs. White explained with a smile). Without a doubt those conversations were the early beginnings of my journey to becoming a writer.

“You have a way with words, Christine,” Mrs. White once told me. But it’s only because she was my English teacher—the first and only English teacher to ever insult me—that I learned to love them.

...

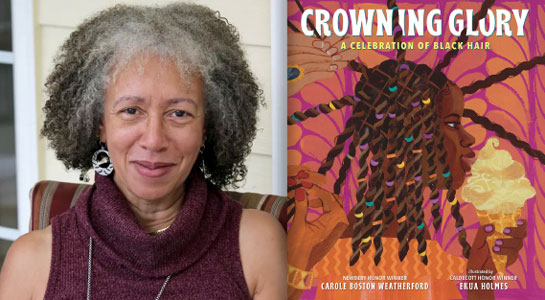

Photograph © Carole Boston |

From Carole Boston Weatherford, author of Outspoken: Paul Robeson, Ahead of His Time (2024, Candlewick), and of the forthcoming picture book Crowning Glory: A Celebration of Black Hair (Sept. 2024, Candlewick)

Around the time of my breakthrough book, Moses: When Harriet Tubman Led Her People to Freedom (Little, Brown, 2006), illustrated by Kadir Nelson, I was invited to keynote a breakfast in Baltimore. My head was in the clouds about speaking in my hometown for an organization my mother belonged to and before hundreds of adults, an audience I rarely addressed back then. On the short flight to Baltimore, I thought about my speech, about my late father, and, for the first time in years, my fifth and sixth grade teacher, Lorraine Hayes. The weekend would be complete, I said to myself, if she were at the breakfast.

The night before, the host organization held a reception for new members. I was there to sign books. Among the new members was Mrs. Hayes’s daughter Patricia, by then an assistant principal. I asked about her mother. “Mama is here,” she said. Up walked Mrs. Hayes in a gray silk suit to match her blue-gray pixie cut. We both exclaimed, then embraced. When we stopped hugging, our eyes had teared up. “I always knew you could do it,” she said as I autographed a book for her.

At all-Black Edgewood Elementary School, Mrs. Hayes created opportunities for her students to shine, from the bulletin board to the auditorium stage. Her classroom was part grammar school, part finishing school. She invited community leaders to mentor us. She organized museum trips, exposed us to classical music, and shared such Langston Hughes poems as “The Dream Keeper,” which encourages self-determination.

Mrs. Hayes’s teaching career spanned 45 years. Under her wing, I felt as if the world was my oyster. I owe her pearls of gratitude.

During my speech at the breakfast, I asked Mrs. Hayes to stand. A few weeks later, a letter arrived. It was written on ivory stationery and enclosed in a gold foil-lined envelope. “Your speech…was such an inspiration,” Mrs. Hayes wrote. The lady was a class act.

...

From Jorge Lacera, co-author & illustrator of The Wild Ones/Los Bravos (2024, Lee & Low Books)

During big chunks of middle and high school, I must admit, I was a bit of a punk. I attended art schools for both, feeling like I had it all figured out. Though I possessed some talent, I failed to grasp the importance of the hard work required to hone my skills. Then came Efrain Montesino, my drawing and painting teacher in middle school, who, coincidentally, ended up teaching at my high school as well. He taught me invaluable lessons in patience, focus, and self-awareness. Through his guidance in drawing and observation, as well as his tough crits mixed in with some encouragement, I gradually understood the hard work necessary to pursue a career in the arts. Efrain Montesino’s influence played a pivotal role in shaping my artistic journey and instilling within me a deeper appreciation of dedication and perseverance.

From Megan Lacera (Megan Newcomer in 4th grade), co-author of The Wild Ones/Los Bravos (2024, Lee & Low Books)

In fourth grade, I moved to a new city. The move meant a transition from a Montessori school to a public school. And, wow, the change was painful: new friends, new activities, and a whole new way of learning. The environment I was familiar with offered more student autonomy and more freedom of movement in the classroom. I had never sat at a traditional desk before! My confidence took a hit. I remember feeling lost and overwhelmed for weeks.

Miss Brediger could see I was struggling but also that I was ahead of my peers academically. That gap wasn’t helping; I felt unchallenged and bored. When there was free time in the day, she asked me if I wanted to try some higher-level work. Yes, please!

Soon, Miss Brediger pushed for me to move up to the fifth-grade classes for math, reading, and English. That shift helped a lot. She also pushed for me to be evaluated for the Advanced Studies Program (ASP). It worked—the following year I joined ASP and started to find my groove again.

I know it took extra time and energy for Miss Brediger to figure out what I needed to thrive as a student and to advocate for me. She believed in me. I felt that then and I can still feel that now. When someone acts on your behalf, it builds confidence and hope. As a writer, I hope to help readers feel a little more confident, a little more capable, a little more hopeful about what lies ahead. Thank you for inspiring me, Jeanne Brediger!

...

From RaQia Lowo, debut author of Weekend and Zay: Saturday School (2023, Reycraft Books)

Growing up a Black child in the 60’s, I was bused to school. In fact, I caught the bus to my elementary school right in front of my neighborhood school. Although my school was a good experience, I don’t recall a teacher that impacted my journey to become an author.

Fortunately, I’ve been blessed with a teacher, friend, and former colleague who has encouraged me through all my adult creative and academic endeavors.

I’ll never forget the day I met Dr. Sheryl Robinson. I was working as a paraprofessional and had written a skit for students to perform during our Black History Month program.

“We’ll Be History” was the name of our skit. Well, we were about to make history, alright. There was only one mic for a dozen or so kids seated at desks across the stage. Several students forgot their lines, not that you could hear them. Except for the one student who kept randomly repeating his line, “Well, you gotta start somewhere.”

We were tanking!!

That’s when Dr. Robinson hopped up and grabbed the mic. She said something like, “This is too good. We need to hear this.” Dr. Robinson proceeded to sit on the stage (which was only about two feet off the ground) and scoot across it in her beautiful African attire. She held the mic in front of each student as they recited their lines.

That’s when I knew she not only had a heart for kids, but she saw my vision and was willing to help me as well. We went on to do various afterschool programs together.

When my book Weekend and Zay: Saturday School launched with a thud of shipping delays, listing errors, and heartache; Sheryl was right there. She assisted with events, ordered books for me, and gave books away to teachers. Most importantly, she continually speaks words of encouragement to me and prays for my success.

What I lacked in encouragement in school during my formative years, I received working in a school as an adult. As a newbie author in her 60s who writes for reluctant readers, I hope I can do the same for children and adults. You’re never too old to make a good impression—or be an inspiration!

...

Photo by Vania Stoyanova |

From Karen Strong, author of Eden’s Everdark (2022, Simon & Schuster) and the forthcoming The Secret Dead Club (August 2024, Simon & Schuster)

I still remember Mrs. Evans’s soft voice and her big glasses. I was the only left-handed student in her first-grade class. In kindergarten, I struggled with holding my pencil. But my luck was about to change because Mrs. Evans was left-handed. She patiently taught me how to hold my pencil in a way that worked for me. Once I found my form, I beamed with pride when Mrs. Evans complimented me on my letters and numbers and encouraged me to write down the stories she’d heard me tell at recess. My parents already knew about my vivid imagination, so I owned a notebook—the cover had a jean jacket with a red apple patch on the pocket. My spelling and sentence structure was still developing at seven years old, but writing in that notebook gave me so much joy. I didn’t know it then, but my first grade teacher sparked my love of writing. Over the years, I would fill up many other notebooks with many stories, and I credit Mrs. Evans for creating the foundation for me to become a novelist.

...

Photograph © York Wilson |

From Scott Reintgen, author of A Door in the Dark (2023, Simon & Schuster), A Whisper in the Walls (2024, Simon & Schuster), and the forthcoming The Last Dragon on Mars (Oct. 2024, Simon & Schuster)

In high school, I was secretly a writer. I’d sit in front of our desktop computer working on a sprawling fantasy book. I told exactly zero people about my pastime. When people asked what I did over the weekend, I didn’t want to tell them, “I wrote about dragons. Again.” But when you really love something, it’s hard to not talk about it. I found myself itching to share the story with someone. There was also a terrifying question I desperately needed answered: Am I any good at this?!

I spent hours editing the first chapter of my book. I polished every word, every sentence. When I was convinced it was as good as I could make it, I printed that chapter out and took it to school. I’m sure it won’t surprise you to learn that the one person I felt it was safe to share my work with was a teacher.

My junior year English teacher—Mrs. Lobasso—was the kindest person I’d ever met. Even on a bad day, you’d leave her room feeling like the sun was shining a bit brighter. And so, with trembling hands, I uncrumpled the chapter in my bookbag and asked if she would read it for me. Keep in mind: I was not a great student. I slept in class. But Mrs. Lobasso simply beamed back at me and said, “Of course!”

The next day, Mrs. Lobasso gave a speech. It was all about believing in people and thinking the best of them. After class, she pulled me aside and said, “Scott. I was talking about you!” She had read my work. The entire chapter. And she’d loved it.

“You know how you’re in Spanish III?” she asked.

“Yes. I need that to get into UNC.”

“Well, you’re not in that class anymore. You’re in Creative Writing now.”

Most people can’t point to one moment that led to where they are now, but I suppose I’m one of the lucky ones who can. My book A Door in the Dark was a New York Times bestseller—but none of that happens without someone taking a moment to say, “Go, love what you love without apology.”

Later this year, my 30th book is set to release. High school me would have been a little embarrassed to talk about it, but adult me will proudly tell you: it’s all about dragons.

...

Photo by Kelly Downs Photography |

From Traci Sorell co-author of Mascot (2023, Penguin) and forthcoming picture book, Clack, Clack! SMACK! A Cherokee Stickball Game (August 2024, Charlesbridge)

Juanita Clark remains the first person other than my mom—and a few others—who believed I could do anything. I certainly lacked that belief in myself as a child. My curiosity always propelled me forward to new adventures and experiences, not confidence.

Mrs. Clark entered my life at age nine when my elementary school tested me for its gifted and talented program. As the gifted coordinator for our Title I rural school district (in addition to teaching high school history), she never stopped moving between the three schools and all her students. Yet I always felt she had time for the dozen of us in my grade. She challenged us with logic puzzles, taught us how to use the computer (way back in 1983), took us to the opera, helped us plan for higher education opportunities, and connected us to the broader world we lived in but had not yet experienced.

After my parents’ divorce and their remarriages, I moved to Southern California with my mother and her new husband. I thought Mrs. Clark’s presence in my life would diminish. I’m grateful I was wrong.

For more than 40 years, Juanita Clark has remained in my inner circle—a close confidante and second mother. When I left the law and policy world, when I became a mother, and later when I transitioned to writing books for young people, her steady support, advice, and love never faltered.

At 91 years young, she and I text several times a week and continue to see each other regularly. Her ongoing presence in my life is an amazing gift. I never want to take it for granted. Great teachers deserve respect, support, and much higher compensation for all they do.

Wado (thank you) to teachers who believe in their students, especially when those young people might not be able to do that for themselves.

Daryl Grabarek is a former SLJ editor.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!