Native YA: Four Native American Authors on Their Messages for Teens

Indigenous stories—contemporary, historical, and fantastical—have an important place in the YA lit scene and the larger conversation of stories for our youth. They are an education on indigeneity and the sovereignty of more than a thousand Native and First Nations on the continent, more than 500 in the United States alone.

Native YA literature is also fun, thoughtful, and full of heart. I asked four talented Native YA authors—Joseph Bruchac (Abenaki), Dawn Quigley (Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe), Eric Gansworth (Onondaga), and Cynthia Leitich Smith (Muscogee [Creek])—four questions about Native books for teens and their own roles as storytellers and educators.

1. What messages do you want to share with Native teens?

2. Why these stories, and why now?

3. What advice do you have for educators and caregivers looking to dive into Native YA and share it with young people?

4. Why is your work and Native YA central to conversations about inclusivity, diversity, and social justice in children’s and YA publishing?

I hope to get several messages across to Native teens, who find themselves under pressure from so many directions these days. They have one of the highest—if not the highest—suicide rates in this country. One message: our stories, histories, and languages should be listened to and respected. Too often, Native people have been ignored, stereotyped, and infantilized—not just in literature, film, and popular culture, but in legislation and government practice.

Another message is that growth and change are possible. I saw that in my own life. Further, do not be afraid to tell your own story. Respect yourself and your own place in the circle, while also giving others the sort of respect you want and deserve.

My stories, including my new novel, Two Roads, attempt to get such messages across by truthfully presenting the Native side of the story. I try to create characters who may not be perfect, but who don’t give up while experiencing growth and change through knowledge of their history, culture, and identity.

Two Roads deals with events near the end of the Great Depression, just before Roosevelt’s New Deal. It was a time of despair and uncertainty—the wealthy controlled the government while millions were homeless and impoverished. American Indian boarding schools were at their height—but about to go through changes after a government commission found shocking patterns of abuse. It was a time of civil action—thousands of World War I veterans of many races marched on Washington to demand their war bonus pensions. There are some real parallels to America in 2018.

I do not know of other teen stories that explore this period through the lens of a Native young person’s perspective. The fact that my protagonist and his father are hobos, and that he is being sent to an Indian boarding school by his father, are also, I believe, unique.

I do not know of other teen stories that explore this period through the lens of a Native young person’s perspective. The fact that my protagonist and his father are hobos, and that he is being sent to an Indian boarding school by his father, are also, I believe, unique.

I strongly advise educators engaging with Native YA literature to familiarize themselves—through primary Native sources and not just the Internet—with individual tribal Nations, their histories, and cultures. When preparing to teach one of Tim Tingle’s books drawing on Choctaw history, find out about that history. Look for historical and other sources by qualified Native historians. Go to the websites of tribal Nations. Turn to Native librarians and children’s literature specialists like Debbie Reese.

Visit the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian. Meet Native American people who are culture bearers—but do not assume every Native American knows everything about their tribe or others. Also, please, don’t single out Native kids in your class and expect them to be experts.

I attempt to do two things that our traditional stories always do—entertain and teach. I also try to be scrupulous in my research, turn to elders for advice, and remember that the first thing I need to do—as do we all—is to listen.

My message is to be proud of your Native history, language, and culture. Find yourself in a book by a Native author to learn about teens like you and to understand how challenging it can be to navigate adolescence while growing into your Native American identity. We write books for you because we know the amazing cultures and traditions you carry inside. Sometimes they are just waiting to emerge even brighter.

I wrote Apple in the Middle because I wanted my own children to read a contemporary story about a quirky, oddball Native teenager who is Native and white. I wanted a story where humor, culture, and mystery show that there’s not just “one way” to be an Indian.

Also, I wished to showcase our incredibly beautiful culture. The negative aspects are there, but Native people are far more than loss and trauma. We are the original people, and my book shines a light on our positive spirits.

Educators, you are the gatekeepers to the Native stories young people read. You are the filter through which students learn about our cultures. So find the resources to understand how to locate and evaluate Native-voiced books. Start with Cynthia Leitich Smith and Debbie Reese’s sites.

I remember the first time I finally saw myself mirrored in a story. It was in my favorite book, A Winter’s Count, which is a traditional Lakota pictographic retelling of a battle or hunting story. Around fifth grade, I attended Girl Scout camp and brought this book with me to help me feel less homesick. I had read A Winter’s Count over and over with my mother back home.

I remember the first time I finally saw myself mirrored in a story. It was in my favorite book, A Winter’s Count, which is a traditional Lakota pictographic retelling of a battle or hunting story. Around fifth grade, I attended Girl Scout camp and brought this book with me to help me feel less homesick. I had read A Winter’s Count over and over with my mother back home.

After returning from camp dinner one night, I found one of my cabin-mates reading my book in a melodramatic, stereotypical “Tonto-Injun talk” voice. The girls doubled over in laughter. I made excuses about why I had brought the book and hid it away for the rest of camp, along with my identity as a Native person. When I returned home, I gave my treasured book away and hid my Native identity for many of my school years.

This experience motivated me when I became a writer. Too many Native American schoolchildren feel as though they must hide their identity while enduring biased, racist, and stereotypical literature taught in school. My own children have brought home books with phrases like “those dirty Indians,” full of false notions such as “Indian people did not know how to tell time.”

Every time I pass a used bookstore, I look for A Winter’s Count so that I may complete the circle and return once again to my first beloved Native book.

Photo by Mark Dellas

Eric Gansworth

We each bring experiential knowledge to our writing. My experiences involve negotiating Rez (reservation) culture and pop culture. I want to offer confirmation that you don’t need to embrace one or the other exclusively.

In my novel Give Me Some Truth, I thought that exploring the lives of two Rez kids making their own negotiations would celebrate the inventiveness I love in my community. I wanted to include characters with a range of ethnic appearances, like the people from my community. In Tuscarora Nation, NY, where I grew up, some people look stereotypically Indian, while others can pass for white but still have enough Indigenous features that other Indians can spot. I like to explore the ways we inaccurately imagine others’ lives. My character Maggi is clearly identifiable as Indian, and various other characters make assumptions about her based on their cultural misconceptions.

I also tried to come up with a new term for people like Carson—people like me. Around Indians, people assume I am Indian. But my features are ambiguous enough that when I am around white people, they often think I am white—and speak freely, thinking they are only in white company. It is often ugly enough that I felt this story needed to be told. I developed my own neologism, ChameleIndian, a splicing of Chameleon and Indian. Neither being easily recognized or living stealthily is better than the other.

I’d advise educators to be aware of their own biases, even if they might be perceived as positive ones. I’ve been struck by the number of people who project a spiritual quality onto me, because they believe Indians are inherently more spiritual. That perception isn’t coming from anything I’m doing or saying, so it can only be coming from stereotypical ideas others have about Indians being “closer to the earth spirits.”

I’d advise educators to be aware of their own biases, even if they might be perceived as positive ones. I’ve been struck by the number of people who project a spiritual quality onto me, because they believe Indians are inherently more spiritual. That perception isn’t coming from anything I’m doing or saying, so it can only be coming from stereotypical ideas others have about Indians being “closer to the earth spirits.”

Some people might think such an idea is complimentary. But it isn’t if it has nothing to do with you. It only means that someone is embracing preconceived notions. I grew up exceptionally poor, in a household that was not meaningfully religious in any sense. There is nothing inherently spiritual about poverty, chaos, and hunger.

I write from my experience—growing up in a reservation setting, keenly aware of the bearing that centuries-old treaty negotiations had on my life and my community. This reality brings social justice into play, beyond diversity and inclusivity. In fiction, you rarely see accurate Indigenous characters born in the geographic United States. We are legally citizens of separate sovereign nations, with our own customs, laws, calendars, religions, governments, etc. I commonly hear this phrase “we are a nation of immigrants,” and that is not entirely true. Every time we hear that, we grow a little less visible. Our numbers are small, but we’re still here. If there is a drive for full inclusivity, characters who belong to sovereign Indigenous nations should exist.

Photo by Sam Bond

Cynthia Leitich Smith

Big picture: I want Native teens to know their stories matter—whether they’re page-turning stories about dynamic, rounded characters; narratives about teens with strengths and flaws; or exciting, funny, heartfelt, romantic, you-name-it stories.

I hope you’re all familiar with Rudine Sims Bishop’s “windows, mirrors and sliding glass doors” metaphor about diversity in literature. Native teens belong in the world of books and can be heroes, too.

Basic, right? But it still needs to be said. Too much Native content still reflects flat, New Agey and “Wild West” Hollywood stereotypes. Or what author Ixty Quintanilla calls a “salad-bar approach”: shoehorning in one cultural element without context. Our teens—all teens—deserve better.

My novel Hearts Unbroken centers on the controversial, Hamilton-esque casting of a high school musical—the fallout of Native kids and kids of color landing roles not envisioned for actors who look like them.

The story also explores speech—journalistic, political, artistic, religious, and interpersonal, as well as speech rooted in hate. It asks big questions: Can you separate the artist from the art? Doesn’t every kid deserve a fair shot at the spotlight? All that is wrapped in a romance about a Muscogee girl and an Arab American boy who are trying to make sense of themselves, each other, and their relationship.

My heroes are tested. Growth is hard-earned. But their lives are also infused with love, humor, faith, and gratitude.

I recall a beaming girl at a Houston school visit. She rushed to tell me that she was from the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. We quickly established that her grandparents lived near one of my aunties.

I recall a beaming girl at a Houston school visit. She rushed to tell me that she was from the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. We quickly established that her grandparents lived near one of my aunties.

Afterward, the teacher mentioned how much it had meant to the student to meet a Native author. “I had no idea she was Indian,” that teacher said. “I assumed she was Latina.”

“Maybe both,” I replied.

Always assume there are Native kids in your schools. We are still here. Frame your collections, programs, and conversations accordingly. We need Native YA literature to entertain, illuminate, build empathy—stories that smash misrepresentations, raise awareness, and get kids reading.

Hearts Unbroken is loosely inspired by my own high school experience. My protagonist is a smart, awkward, loving, self-absorbed, principled girl. Imperfect, but well-rounded and relatable.

No, she’s not “representative” of Native teens. We’re talking about hundreds of distinct Native and First Nations. There’s no such thing as representative, and maybe that’s the point—we have a chance to spotlight wholly Indigenous and yet utterly individual heroes.

Alia Jones is a senior library services assistant at the Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, OH. She blogs at readitrealgood.com.

A NATIVE YA READING LIST

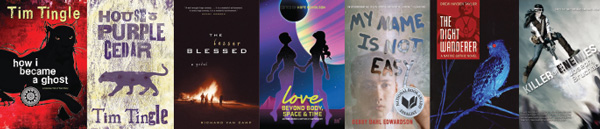

By Alia Jones Apple in the Middle by Dawn Quigley (North Dakota State University Press, 2018).

Apple in the Middle by Dawn Quigley (North Dakota State University Press, 2018).

Bicultural Apple Starkington feels stuck in the middle, not quite Native (Ojibwe) or white.

Crazy Horse’s Girlfriend by Erika T. Wurth (Curbside Splendor, 2014).

Sixteen-year-old Margaritte is a drug dealer determined to escape her Colorado town.

Dreaming in Indian: Contemporary Native American Voices ed. by Lisa Charleyboy and Mary Beth Leatherdale (Annick, 2016).

An anthology of art, poetry, photography, and short stories by people of various Native Nations.

Fire Song by Adam Garnet Jones (Annick, 2018).

Shane struggles to find himself on the reservation as he tries to heal from his little sister’s suicide.

Give Me Some Truth by Eric Gansworth (Scholastic, 2018).

Carson and Maggi, two kids from the Tuscarora Nation, pursue their dreams of starting a rock band and making art.

Hearts Unbroken by Cynthia Leitich Smith (Candlewick, 2018).

Muscogee (Creek) teen reporter Louise is paired with Joey, an Arab American photo-videographer, on the school newspaper.

House of Purple Cedar by Tim Tingle (Cinco Puntos, 2014).

Choctaw elder Rose Goode shares the history of the Choctaw town of Skullyville.

How I Became a Ghost: A Choctaw Trail of Tears Story by Tim Tingle (Roadrunner, 2015).

Isaac, a Choctaw boy who has died and become a ghost, tells of his people’s forced removal from their homelands.

If I Ever Get Out of Here by Eric Gansworth (Scholastic, 2013).

Lewis, a kid from the Tuscarora Nation, finds a friend in George, a white kid whose dad is in the U.S. Air Force.

Killer of Enemies by Joseph Bruchac (Lee & Low, 2013).

Lozen lives in a time where The Ones have lost their power due to The Cloud, but their genetically engineered monsters roam free.

The Lesser Blessed by Richard Van Camp (Douglas & McIntyre, 1996).

Larry, a Dogrib First Nation teen, and his Métis friend Johnny navigate life in their town of Fort Simmer.

Love Beyond Body, Space, and Time: An LGBT and Two-Spirit Sci-Fi Anthology (Bedside, 2016).

This anthology celebrates Native Two-Spirit identities and experiences through sci-fi short stories and poems.

The Marrow Thieves by Cherie Dimaline (DCB, 2017).

In a dystopian future, Native people are hunted for their marrow because of its link to their dreaming ability.

Moccasin Thunder: American Indian Stories for Today ed. by Lori M. Carlson (HarperCollins, 2005).

A collection of short stories about American Indian teens.

My Name Is Not Easy by Debby Dahl Edwardson (Skyscape, 2013).

Luke decides to not use his Iñupiaq name when he and his brothers are sent to a faraway boarding school.

The Night Wanderer: A Native Gothic Novel by Drew Hayden Taylor (Annick, 2007).

Tiffany lives on the Otter Lake reservation, where nothing exciting happens, until her father rents out her room to an Anishinaabe vampire.

#NotYourPrincess: Voices of Native American Women ed. by Lisa Charleyboy and Mary Beth Leatherdale (Annick, 2017).

This stunning collection celebrates Indigenous women.

Rain Is Not My Indian Name by Cynthia Leitich Smith (HarperCollins, 2001).

As Cassidy Rain grieves for her best friend, she embraces a photography assignment detailing her auntie’s science camp for Native youth.

Two Roads by Joseph Bruchac (Dial, 2018).

Cal, living a hobo life with his father, learns he is Muscogee (Creek) Indian.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!