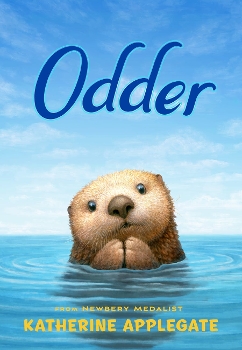

An Exclusive Excerpt & Interview: 'Odder' by Katherine Applegate

An interview with the renowned middle grade author and an exclusive excerpt of her highly anticipated upcoming title, Odder.

In Newbery Medalist Katherine Applegate's latest, Odder, a playful sea otter finds her whole life changed after a dangerous encounter. Based on extensive research conducted on a real otter pup program in Monterey, CA, this poignant tale explores conservation and healing through Applegate's trademark anthropomorphic animal voice and free verse. Before we reveal our exclusive excerpt, enjoy SLJ's interview with the accomplished writer about storytelling, the California Fur Rush, and encouraging kids to become environmental activists.

What was it about otters made you want to create a story around them, and what type of research do you conduct on the animals you feature?

What was it about otters made you want to create a story around them, and what type of research do you conduct on the animals you feature?

Well, let’s begin with the obvious: as I say in my book, there’s no denying that sea otters are the champions of cute. But they’re also fascinating creatures and a keystone species, vital to nearshore ecosystems like kelp forests.

I love doing research, and there are wonderful resources available on sea otters, including breathtaking videos online. But there’s no replacement for seeing otters up close. I visited Monterey Bay to see southern sea otters in Elkhorn Slough, where they live in large numbers, and spent time at the amazing Monterey Bay Aquarium. They’ve been pioneers in raising orphaned sea otters with surrogate mothers, and extremely helpful with my endless questions.

How do you develop each animal’s unique voice and personality—like Odder the otter, who is also known as “The Queen of Play”?

When writing from an animal’s point of view, there’s always a balancing act: anthropomorphism in fiction exists on a continuum. I tried to keep Odder’s experiences as faithful to my research as possible, while giving her an accessible, fun voice that young readers would enjoy.

Odder is a daredevil, and always ready to play. Of course, not every otter is as fun-loving as she is. Just like humans, every animal is unique. Not all dogs are friendly, not all cats are aloof (pet owners know how different they can be). That said, I think the first thing you notice when you watch sea otters in the ocean is the joyful way they all move. There’s no way around it: they look like kids at a water park.

Do you feel your favorite childhood books influence the way you write children’s literature? What are some titles that have stuck with you?

I was slow to embrace reading, and for me, Charlotte's Web by E.B. White was a turning point. I’ve always been an animal lover, and Wilbur and his pals instantly stole my heart. The Cricket in Times Square by George Selden and The Animal Family by Randall Jarrell were other favorites.

I still read Charlotte's Web from time to time, and always find something new to love.

Read: Eight Fantastical Books That Center Black Tweens

Odder’s friend Kairi talks about how sea otters were once down to just 50 in the species. What messages do you hope readers will take with them after reading this book?

We’ve all heard of the California Gold Rush, but there was also a California Fur Rush. By the early 1900s, the population of southern sea otters in central California waters was down to about 50. Amazingly, they’ve been brought back from the brink with targeted conservation measures. We’ve seen that happen with other species, too—the giant panda, the California condor, for example—and I think it should give tremendous hope to our next generation of conservationists.

Many of your books, including Odder, are written in free verse. What is it about free verse that appeals to you, and how do you decide which format to use when writing?

There are certain stories that benefit from the pared-down format and lyricism of free verse. You still need a strong through-line and characters to love; but with free verse, you can add so much with line breaks, rhythm, and sound. Especially when writing about a world as different from our own as Odder’s, free verse can have a visceral impact you might not achieve with prose.

I noticed that the animals in your stories often have dialogue, while the humans are mostly non-speaking. Can you give us some insight into that stylistic choice?

If you ask me, humans already get plenty of air time!

Odder’s story was inspired by the successful surrogacy programs with otters at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. In what ways can readers help otters or other animals in the wild? What do you think animals can teach children about human relationships?

First of all, young readers need to arm themselves with knowledge. Become the in-school expert on a species, or start a conservation club. Learn about groups that work to preserve endangered species, and raise money for them. Write letters in support of legislation that helps protect species.

First of all, young readers need to arm themselves with knowledge. Become the in-school expert on a species, or start a conservation club. Learn about groups that work to preserve endangered species, and raise money for them. Write letters in support of legislation that helps protect species.

Caring for animals is often one of the first ways children experience responsibility for another living thing. Kids can feel small and powerless sometimes, and when they realize they can be nurturing and protective, it’s truly empowering.

With all of the recognition your books have achieved (including the Newbery Medal and a film adaptation for The One and Only Ivan, and the Golden Kite Award for Home of the Brave), what else would you still like to accomplish in your career? What are you working on currently?

It’s always about just one thing: learning, with each book, how to tell a good story. Every single time it’s like starting from scratch. Which means it’s always terrifying. And always exhilarating.

I’m at work on a couple new middle grade novels right now. They’re still at that delicate, don’t-talk-about-them-or-the-bubble-will-burst phase. But I’m hopeful, and having fun, and that’s a pretty wonderful place to be. I am truly lucky, and I will always be grateful for the chance to do this work.

And now, without further ado, an exclusive excerpt from Katherine Applegate's Odder, coming Fall 2022.

It is a happy talent

to know how to play.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

one

the queen of play

monterey bay, california

and environs

not (exactly) guilty

In their defense,

sharks

do not (as a rule) eat

otters.

True, sharks sometimes

taste them

by mistake, leaving

frowning bites

or the jagged clue

of a tooth or two.

But then,

in fairness,

nobody’s perfect.

too late

Say an empty-bellied

great white shark

is enticed by

a long, sleek swimmer,

a sea lion, perhaps.

(Big fans of

blubber, sharks.)

Curious, the shark

moves in for a nibble,

only to discover he’s

sampling a surfboarder (oops),

or, more likely,

a member of that most

charming branch

of the weasel family,

the southern sea otter.

You’ve been there,

haven’t you,

in the cafeteria line

or the breakfast buffet,

taking a chance on

some new food?

Grab, gulp, grimace:

you spit the offending

item into a napkin,

no harm, no foul.

Same goes for the shark,

who quickly

reconsiders and

retreats.

Of course, by then it’s often

too late for the surfboarder.

And almost always

too late for the otter.

hunger

One such shark

is prowling the waters

this very morning.

It’s daybreak,

cloudless and shell-pink,

and for a moment the bay

seems to blush.

There it is:

his dorsal fin,

cutting through the

calm waves.

The shark is an adolescent—

a marine tween—

streamlined and strong,

but small for his age,

and far from his usual

haunts today.

His last meal,

a ray and two puny turtles,

was three days ago—

pathetic, by any measure.

No need to worry.

Hunger has a way

of focusing the mind.

If there is food

to be found, rest assured:

he will find it.

Otter #132

Not far from the shark,

Otter #132 floats on her back,

forepaws and flippers

held aloft,

soaking up sun

like tiny solar panels.

Tucked in a pocket of skin

under her arm

is a favorite rock,

just right for opening

mussels and clams.

She has seen more

than a few sharks in

her three years,

has even seen them

kill.

But right now her only concern

is what to eat for breakfast.

numbers and names

Friends call #132

“Odder,”

but humans prefer

their numbers.

They count cards and sheep,

errors and at-bats,

minutes and blessings.

Here in the bay,

they count

otters, too.

Squiggles and Splash

There’s a reason

for those numbers.

Turns out names make it easier

to get attached.

Numbers are aloof,

but names are sticky,

fusing rescuer to rescued,

scientist to subject,

human to otter.

(And it’s not hard

to fall in love with

an otter pup.)

It’s a shame, really.

Think of the possibilities:

Squiggles and Splash

and Potter and Noodle!

Otto and Oswald

and Ozzie and Obi!

Still, it’s better this way.

No point in getting too friendly

when the odds are so

long.

questions

Her mother called her “Odder”

from the moment

she was born.

Something about the way

the little pup never settled,

something about the way

her eyes were always

full of questions.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!