Jessie Storrs: Serving “Just Kids” | 2024 School Librarian of the Year Finalist

"It doesn’t really matter what they did out there,” says the teacher librarian, who serves youth from age 10 to their early 20s at El Centro Junior/Sr. High School in the Sacramento County Youth Detention Facility.

School Librarian of the Year Finalist

|

Jessie Storrs, Teacher Librarian/Media Instructor,El Centro Jr. and Sr. High School, Sacramento County Youth Detention FacilityPhotos by Renée C. Byer |

|

School Librarian School Librarian |

When new students enter the library at El Centro Jr. and Sr. High School in Sacramento, CA, teacher librarian Jessie Storrs knows exactly what book they will want.

“They come in here and pick up Diary of a Wimpy Kid, every time,” says the Finalist for the 2024 School Librarian of the Year Award, presented by SLJ and sponsored by Scholastic.

The series is popular for many young readers, but for the students in El Centro, it holds special meaning.

“When I get a kid in here new to the facility, they are both tired and scared, because they have been in booking,” Storrs says. “They are frightened. They are in with a bunch of kids they don’t know. That book is familiar and something they had on the outside.”

El Centro is the on-site education program within the Sacramento County Youth Detention Facility, home to 163 incarcerated young men and women from as young as 10 up to their early 20s. Storrs has been the librarian at El Centro since 2021.

Every day, Storrs passes through multiple high-security checkpoints on her way to her library, which is housed in a 40-by-20-foot decommissioned resident dormitory that the facilities department outfitted with library shelves. Her stockrooms are former inmate cells. The windows are barred.

|

Photo courtesy of Sacramento Probation Department and Sacramento County Office of Education |

Storrs has turned the library into a sanctuary for her students. The walls are bright yellow and decorated with rainbows. She added LED lighting and cozy features like essential oils that emit a soothing scent and displays that change with the seasons.

“I like coming in here because it’s peaceful and I think the kids do, too. It’s a break for them to be around books and things that smell nice.”

Storrs sees each of her classes once a week, and students are rotated through in small groups, with only a few minutes to browse and check out books; those who are waiting participate in library activities. But Storrs and her library partner, probation officer Kathryn Lopez, work to make the most of their time with students outside of those short visits, including visiting dorms and assisting students one-on-one with a literacy incentive program Storrs built, leading board-game clubs, visiting classrooms, and curating book selections for students to check out.

Together, Storrs and Lopez have built a collection that would rival many found in traditional schools.

The library is nearly entirely funded through the community partnerships Storrs has developed. The Friends of the Sacramento Public Library and the Wiley Manuel Bar Association are two of the largest donors. Their support allowed Storrs to curate a contemporary, diverse collection of nearly 22,000 titles. When a student requests a book that’s not on the shelves, Storrs and Lopez typically purchase it on their own.

While the library began as an initiative through the probation office, the space truly became what it is today once Storrs arrived.

“When she came, everything kicked off full force,” Lopez says. “The dynamics have changed tremendously. Jessie’s there for the kids, and you can tell she cares about her job tremendously.”

Storrs credits others for helping the library succeed. “I’m so fortunate to have Officer Lopez, and I’m supported heftily by county probations programming and my administrators, and the teachers want to collaborate with me,” Storrs says.

She regularly visits classrooms to promote reading, play games, and bring students on digital field trips. She also serves as the school’s technology liaison. Students are not allowed hands-on computer activities, so Storrs acts as the intermediary when she visits classrooms—making the most of limited technology available due to safety and security restrictions—bringing along an audio-visual cart and a projector. But even with that, she is restricted.When Storrs teaches internet safety, she must use a pen and paper to show students how to change settings, since social media isn’t allowed; it’s the only way to allow students to practice on their own without a computer.

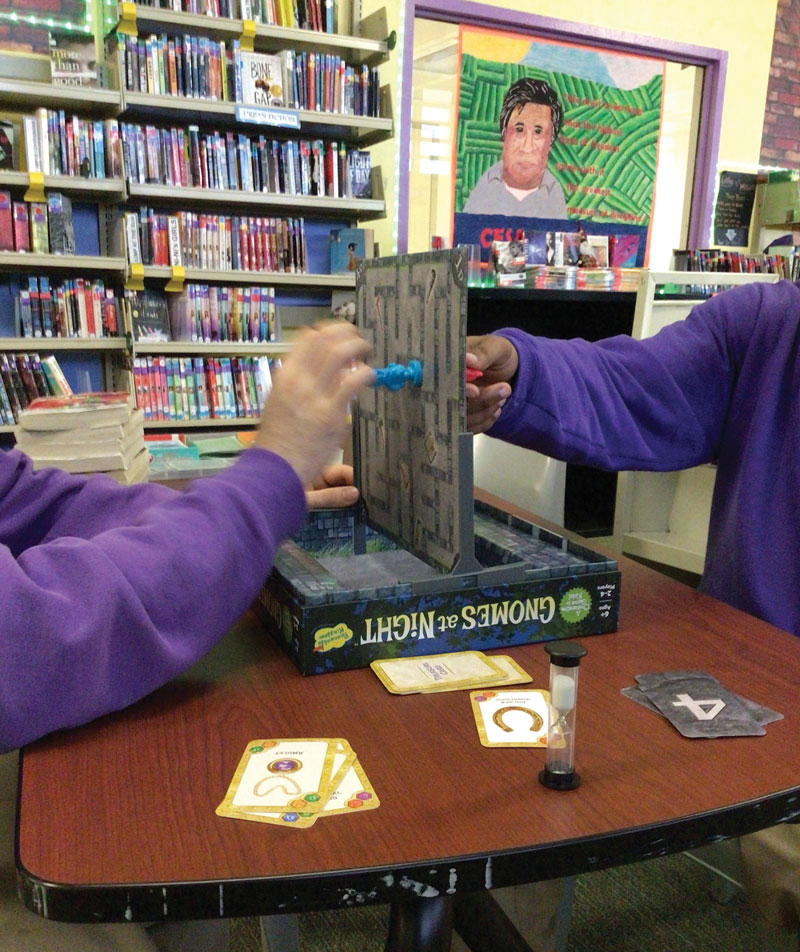

But for everything she has brought to the facility, the biggest impact might be her work around social-emotional learning (SEL). Storrs says that one of her most successful programs is the Game Changers Club, which integrates SEL with board games. Older students are permitted a longer, additional library visit during the week, and Storrs sets up stations where they can learn new games or continue past ones, like the popular Kingdomino. Even during short visits, students have a chance to engage in quick, class-wide games, like a round of Battleship they play against Storrs.

But for everything she has brought to the facility, the biggest impact might be her work around social-emotional learning (SEL). Storrs says that one of her most successful programs is the Game Changers Club, which integrates SEL with board games. Older students are permitted a longer, additional library visit during the week, and Storrs sets up stations where they can learn new games or continue past ones, like the popular Kingdomino. Even during short visits, students have a chance to engage in quick, class-wide games, like a round of Battleship they play against Storrs.

“Between the competitive and the cooperative games, students are learning time management, resilience, learning to listen and follow direction, and work cooperatively,” Storrs says.

Julie Wilde, one of seven teachers in the facility, says her students love the games, and teachers love the SEL components Storrs ties in, like in a recent murder-mystery game.

“It incorporated teamwork and relationship building in a really cool way for my students to strengthen their bond,” Wilde says. “And the kids reference it. They definitely talk about it and feel so proud of all the work they put in to solve it.”

Currently, Storrs is aiming to bring SEL to incarceration facilities throughout California, including in Sacramento, Alameda, and San Diego, through a curriculum initiative funded by a CalHOPE grant. She is also taking part in the Breakfree Education Fellowship, designed for teachers working inside juvenile-justice facilities. With that, Storrs is working on an initiative to bring a textile-production project to her students.

“I’m a spinner, and one thing I’d like to do is teach students how to spin yarn and learn about the sustainability of fiber, how we can make it into something for somebody else and keep the world warm,” Storrs says.

People often ask Storrs how she can work with students who have committed violent crimes. She tells them, “These kids are just kids. It doesn’t really matter what they did out there.”

Despite how warm and welcoming Storrs has made her library, she is acutely aware of her students’ challenges, confined in an environment they have no control over. That’s what drives her to serve them not only with patience, but with love.

“There’s an intrinsic need to see these kids succeed in a place where they might not usually,” Storrs says. “Some succeed, some repeat, but all are special and should be treated fairly.”

|

An annual award presented by SLJ and sponsored by Scholastic, the School Librarian of the Year Award honors a K–12 library professional for exemplary service to students, creativity, outreach, and use of technology tools, along with outstanding teacher collaboration and student engagement. This year’s submissions were judged by Julie Stivers, 2023 School Librarian of the Year; Dr. Kevin M. Washburn, director, library programs, DC Public Schools; a Scholastic representative; and SLJ editors. Learn more about the award and past winners at slj.com/SLOTY. |

Andrew Bauld is a freelance writer covering education.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

ABOUT THE AWARD

ABOUT THE AWARD

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!