Can Diverse Books Save Us?

In a divided world, librarians are on a mission.

The majority of public and K–12 librarians consider it "very important" to have a diverse book collection for kids and teens, according to SLJ's nationwide survey. But there are hurdles, including a lack of quality titles in specific areas.

Related Content

Diverse Books Survey Home Page |

“She gasped when she saw a girl wearing hijab on the cover,” says Deborah Vose, recalling a seventh grader who wandered into her library one afternoon and stood, captivated, before a display of books. Staring at the cover of Brave, the 2017 graphic novel by Svetlana Chmakova, the student grasped the book and exclaimed, “Someone who looks like me!”

It was a brief moment of discovery and connection that would delight any educator, but to Vose, the librarian at South and East Middle Schools in Braintree, MA, it was especially significant. She—like the vast majority of respondents to a recent School Library Journal (SLJ) survey—has made it a priority to bring books reflecting diverse cultures and perspectives to the children and community she serves.

Finding the right book for the right reader is a constant goal of librarianship, but the import of diverse books is bringing new meaning to that effort. “Along with giving students choice [in reading], diversity is the most important issue in the field of teen and children’s literature right now,” says Elaine Fultz, district library media specialist at Madison Jr/Sr High School in Middletown, OH, and among those who responded to SLJ’s survey.

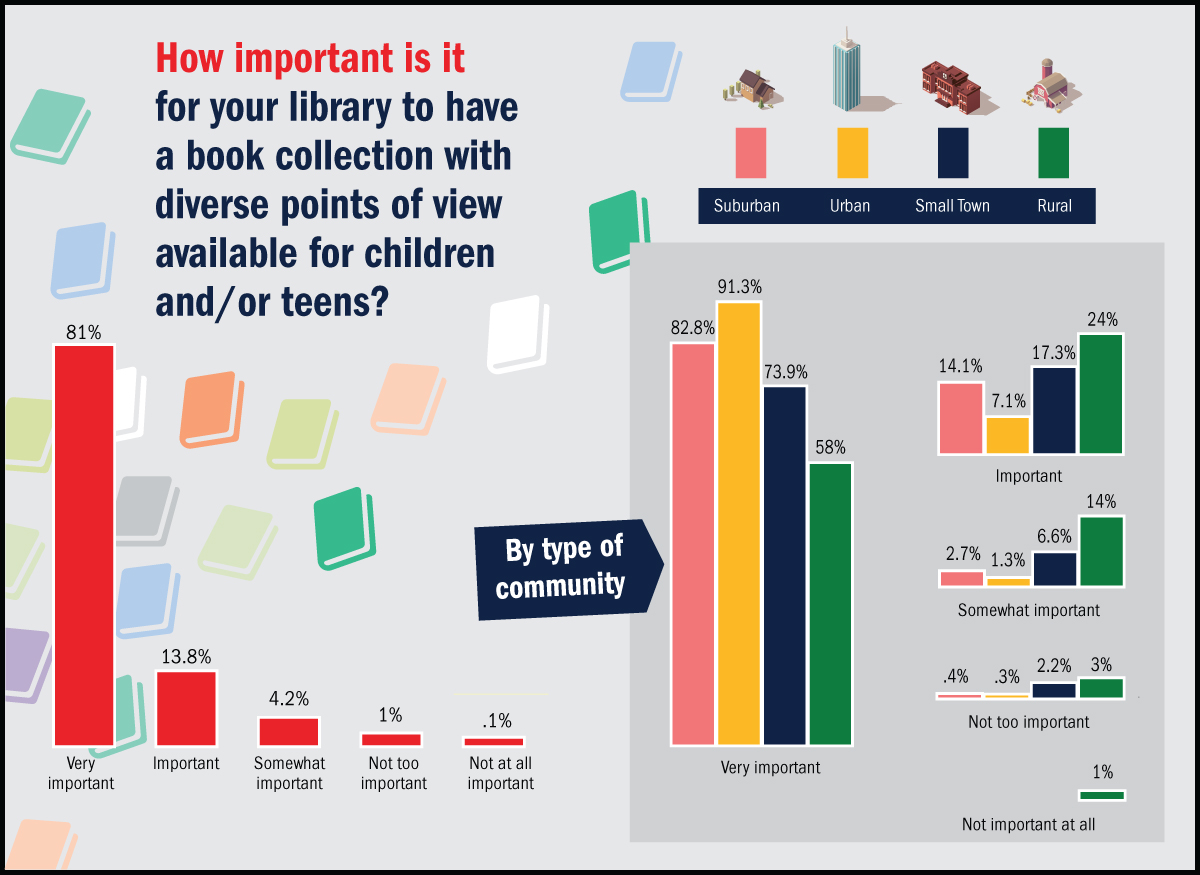

That research, fielded in April 2018, revealed that the majority of librarians, 81 percent, consider it “very important” to have a diverse book collection for kids and teens. (Diverse collections, in this context, were defined as books with protagonists and experiences that feature underrepresented ethnicities, disabilities, cultural or religious backgrounds, gender nonconformity, or LGBTQIA+ orientations.)

Some libraries have adopted diverse content as part of the institutional mission. About half of all respondents (54 percent of public libraries and 50 percent of school libraries) have inclusive collection development goals stemming from their administration or district. This rises to 68 percent in urban communities and 65 percent in private schools.

But a significant driver here is individual conviction—of the 1,156 survey respondents (school and public librarians serving children and teens in the United States and Canada), 72 percent told SLJ they consider it a personal goal to create a diverse collection.

“As a teen librarian in the whitest state in the union, I feel it is my duty to not have the collection reflect my community, but rather to reflect the wider world,” says Melissa Orth, a teen librarian at Curtis Memorial Library, in Brunswick, ME. “Books featuring characters with different cultural experiences from their own can educate teen readers and build empathy.” For Sandra Parks, broadening the collection of her library at Skyline Middle School in Harrisonburg, VA—an effort in which she has focused on acquiring more titles with LGBTQIA+, Muslim, and African American characters and themes—“may be the most important thing I have done in my career,” she says.

Among the respondents fortunate enough to have workplace support, Orth acknowledges her library administration’s standing selection policy of representing “all types of people” in its collection.

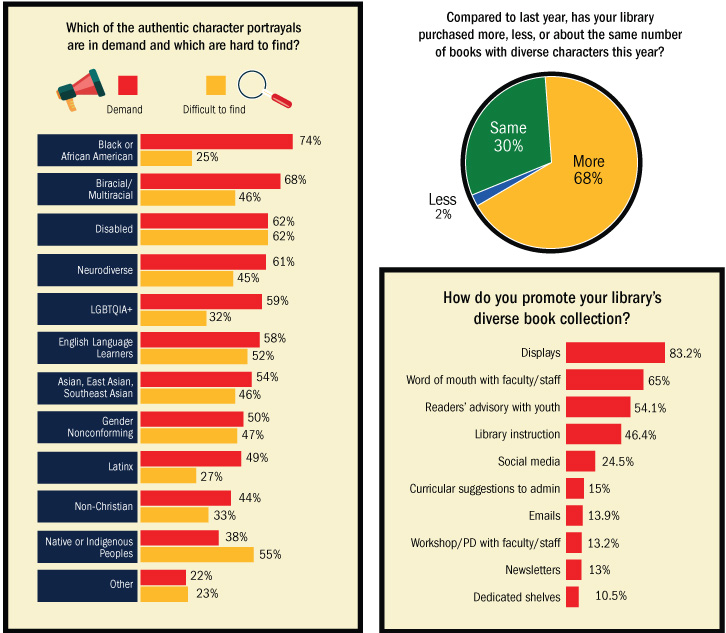

Others have encountered hurdles. Fifteen percent of librarians find it “very difficult” or “difficult” to find suitable titles to round out a diverse collection. Portrayals that are the hardest for them to find? Characters with disabilities, Native or Indigenous peoples, and English language learners top the list.

The potential for a book challenge (the attempt to remove material from the curriculum or library) has kept 13 percent of respondents from buying a work with a diverse character, according to the survey.

Nevertheless, librarians are passionately focused on this goal. A notable sense of urgency to this mission underscores a deep pool of anecdotal comments on the survey.

|

‘A strength of our country’

The issue is hardly a new one. The nonprofit We Need Diverse Books, a catalyst of the movement, launched in 2014 (SLJ dedicated an entire issue to the topic that same year). Ongoing efforts from inside and outside the publishing industry notwithstanding, building diverse collections at the ground level—where young readers can directly encounter the mirrors and windows in which they see themselves in books and others who are not like them—may be where the rubber hits the road.

And it couldn’t be more critical.

“I feel it is essential to educate my students, so they do not see diversity as a problem, but rather as a strength of our country and community,” says Nancy Snow. A school librarian at Bancroft Elementary School in Andover, MA, Snow was among those who referenced the current political climate in their responses to SLJ’s survey.

Indeed, deep divisions continue to roil the nation, and racism and intolerance are directly impacting students on and off campus.

From swastikas scrawled on walls to racial slurs passed in notes, hundreds of verified accounts of racist, xenophobic, or homophobic acts in school dating from 2015–17 prompted an examination by ProPublica and Education Week in a recent joint project. The largest number of reports on a single day in K–12 schools occurred on November 9, 2016—the day after President Donald Trump’s election.

From swastikas scrawled on walls to racial slurs passed in notes, hundreds of verified accounts of racist, xenophobic, or homophobic acts in school dating from 2015–17 prompted an examination by ProPublica and Education Week in a recent joint project. The largest number of reports on a single day in K–12 schools occurred on November 9, 2016—the day after President Donald Trump’s election.

Almost all of the anti-immigrant incidents in schools tracked by Teaching Tolerance since October 2017 have targeted Latinx students and included the phrase “build the wall,” a campaign pledge by Trump, who has used derogatory and racist language to describe people of color and other minorities.

Anti-Semitic and anti-LGBTQ harassment and bullying were significant in Teaching Tolerance’s report of 495 school hate incidents. “But black students bore the brunt of the hate,” according to the nonprofit organization’s website, which documented various expressions of the “N word,” verbal and written, and worse. Bear in mind that this study, as with ProPublica’s Documenting Hate project, only accounted for incidents that were reported; the actual experience of bigotry suffered by children and teens is likely beyond measure.

“Anti-blackness is at an all-time high,” says Kim Parker, assistant director of teacher training at Shady Hill School in Cambridge, MA. “And I think that however we can disturb those notions, we can remind children of color that they are beautiful and they are powerful, and we can provide literature that affirms them…. That’s the work we need to do right now.”

Growing demand

In her school community, instances of bullying have gone up, says Snow. “I don’t know if it’s race, but there’s a lot of unkindness.” She wants her students, who come from all over the world, to feel welcome “and see books in my cases, on tops of bookshelves, and it somehow might counter what they’re seeing in the news,” says Snow, who notes there are more quality titles available toward this goal.

Across the board, librarians are buying more diverse books—two-thirds of the sample, 68 percent of survey respondents, report purchasing an increased number of children’s/YA (young adult) titles with diverse characters in the last year. Segments that exceed this percentage include public libraries (73.4 percent); private schools (74 percent); libraries in urban and suburban communities (71.8 percent and 70 percent, respectively); and libraries located in the Northeast (73 percent).

“Buying every diverse book I can, especially ones by diverse authors,” comments Kacy Helwick, youth collection development librarian at New Orleans Public Library. “Latinx, for early readers especially,” says Janet Parker, citing one purchasing priority. The library media specialist at Elizabeth Hall School in Minneapolis, Parker is also purchasing LGBT titles across the collection.

Fully 98 percent of librarians surveyed are involved in the recommendation or purchasing process of children’s/YA titles for their institution. They enjoy great latitude in diversifying their collections, to boot—84 percent have final say in book purchases. Yet librarians aren’t always finding what they’re seeking.

“Please, more books about Muslim kids. Also Black Muslim kids. My students are Somali—there are no books that I can find published by big publishers,” commented Anna Zbacnik, a media specialist at Brimhall Elementary in Roseville, MN.

In Brunswick, Melissa Orth has difficulty finding contemporary stories of East Asians. Other librarians also seek non-historical portrayals of various cultures and ethnicities and ones that bust stereotypes and “single story” narratives.

“I am trying to find books where there are kids or teens just living life while black/gay/trans/fat/Muslim, etc.,” says Libby Edwardson, youth services librarian at Blue Hill (ME) Public Library. “Not that they ignore the challenges that accompany being a minority, but kids want to see mirrors of themselves in books. They don’t want to always have to see characters that represent or teach something bigger than themselves.”

The hand-sell

And how do kids respond? “The LGBTQA+ books are flying off the shelves with long wait lists,” says Jill Johnson, library media center director at Jefferson Middle School, in Aurora, IL. “My African American boys can’t get enough of Kwame Alexander and Jason Reynolds,” says Zbacnik. Tini Maier, librarian at Jackson Middle School, also cited Alexander and Reynolds as among several authors of color who are popular among students of all backgrounds at her Portland, OR, school, which she describes as primarily white.

But “selling” diverse titles in the library has also yielded mixed results. While some kids specifically seek out books in which they see themselves represented, others simply aren’t as aware of available works or don’t have an easy pathway to connect with them.

Librarian Bethany Payne isn’t sure if diverse books are any more or less popular at her school, CW Dillard Elementary in Wilton, CA. “But I recommend them based on the story and try not to make a big deal about their diversity,” she says. Indeed, a compelling, quality narrative is key to grabbing a reader’s attention, say librarians, and ultimately the bottom line for them when it comes to deciding to buy a book or recommend one. Genre, too, is a factor in getting kids to engage with books, with graphic novels a popular draw among all ages, with or without diverse characters.

If not all kids are inclined to explore an inclusive collection on their own, the librarian becomes even more critical. To get these books into distribution, librarians create displays; it’s the number one method of promoting books with diverse themes and characters. Readers’ advisory is a close second among public librarians.

If not all kids are inclined to explore an inclusive collection on their own, the librarian becomes even more critical. To get these books into distribution, librarians create displays; it’s the number one method of promoting books with diverse themes and characters. Readers’ advisory is a close second among public librarians.

A MOSAIC in the midwest

To really make an impact, diverse books must be infused into the school curriculum, a sentiment echoed throughout the survey in which librarians reported various efforts to work with teachers to make this happen.

“It’s also important to be supportive at the district level and down,” says LaVonne Latham Hanlon. A library media specialist at Sheridan Elementary School, in Lincoln, NE, Hanlon should know. She’s a member of Lincoln Public Schools’ (LPS) Multicultural Book Review Committee, created to identify and recommend high-quality titles district-wide, culminating in MOSAIC, an annual celebration and display of diverse books. “We encourage all staff members in the district to view these selections, and we participate in hosting traveling exhibits [of the books] in school libraries,” says Hanlon.

LPS launched the effort in 1991 in response to a new rule of the state DOE that required schools to include in their libraries current and unbiased information about different cultures. The district has been promoting diverse content ever since.

LPS launched the effort in 1991 in response to a new rule of the state DOE that required schools to include in their libraries current and unbiased information about different cultures. The district has been promoting diverse content ever since.

“We know that it is critical for kids to find themselves reflected in books,” says Chris Haeffner, director of library media services at LPS, Nebraska’s second largest school district, which serves 40,000 students in 60 schools.

“Our media specialists are doing an amazing job. With all the time they spend in the classroom working with students, they don’t always have the time required to research and review all the new multicultural titles that fit within the Nebraska Department of Education’s Rule 16,” says Haeffner on the district website. “The MOSAIC display serves to inform all of our librarians, teachers, and curriculum specialists about the rich multicultural resources we have available to us.”

Totaling 190 books, this year’s MOSAIC list features book trailers and related teaching resources.

Of the good work around diverse books, “it’s happening in pockets,” says Kim Parker. “There are some incredible librarian activists, and maybe amplifying their voices, putting them at the center of conferences, and getting them to publish best practices with kids who need it the most,” she says, will help the movement scale.

For now, it may be a leap of faith on the part of librarians that kids will pick up these books and become passionate, lifelong readers; that doing so will engender empathy; and that tolerance and understanding will resonate through their respective communities and the nation.

Can books really change the world? “It can’t hurt,” says Nancy Snow. “We can help develop empathy if we read books about others and try to put ourselves in their shoes. That’s all we can do. If we can’t put them physically together, we can give them other people’s stories and talk about them. I’m hoping I can make a difference.”

|

Survey Methodology: The SLJ Diverse Book Collections Survey was emailed to a random selection of 22,000 school and public librarians from SLJ newsletter lists on April 27, 2018. The study was promoted in SLJ’s Extra Helping newsletter and via social media. It closed on May 15 with 1,156 responses from the United States and Canada. |

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

lisa sherman

My problem is finding many books that highlight the difficulties that (x) group encounters and not enough where the characters are just a part of (x) group, with normal lives. No shootings, drugs, gangs, broken homes, or stereotypical situations/lifestyles.Posted : Nov 07, 2019 10:07