Boston’s Revolutionary Pledge: A School Library for Every Student by 2026

This year, BPS will see 25 new libraries along with 30 new librarians, with funding to ensure an opening day collection of new, culturally sustaining books.

|

BPS assistant director of library services Felicia Humphries, Fenway librarian Bonnie McBride, and director of library services Liz Phipps-SoeiroPhotos courtesy of Boston Public Schools |

At Fenway High School in Boston, the school library is beloved. Literally.

“I regularly hear from students about how important it is to have a library,” says Fenway librarian Bonnie McBride. “It’s a safe space for them. Students even write Valentines to the library in February. You see how important it is to them.”

Those Fenway students are some of the lucky ones in Boston Public Schools (BPS), where the majority of students lack access to a library and staff. McBride herself is one of the few remaining school librarians in the city.

But now, all of that’s changing as Boston is investing in an ambitious new initiative that promises every Boston Public School access to a school library program by 2026. It’s a major turnaround for the city, and a rare bright spot at a time when districts around the country are slashing library budgets and hemorrhaging staff.

“I’m so excited that all students in Boston will be able to experience what my students have,” McBride says.

An ambitious investment

For too long, the majority of BPS students have gone without access to a full-time library or librarian. Last year, out of Boston’s 125 campuses, only 52 schools had their own full-time library and staff.

According to The Boston Globe, BPS lost one-third of their library facilities between 2009 and 2021 due to school closures and budget cuts. Over that time, the divide between the haves and the have-nots only grew more extreme. Prestigious exam schools like Boston Latin School today offer students a modern library space featuring two certified librarians, while, at Dorchester’s McCormack Middle School, students hadn’t had access to a school library since theirs shut down in 2008. It took teachers and community members raising more than $20,000 on their own to finally restore a library space in 2015. And even then, it still lacked a certified librarian and relied on volunteers and teachers to keep it going.

But after years of struggle, the Boston School Committee offered reason to hope last October when it passed the new Library Services Strategic Plan under the leadership of former superintendent Brenda Cassellius, who left the position in June. While there were fears the plan could lose momentum under a new administration, the library investment is central to the future goals of BPS.

Liz Phipps-Soeiro became director of library services for BPS this fall, taking the reins from longtime director Deborah Lang Froggatt. Phipps-Soeiro says that the new initiative has truly been a team effort.

“It’s been a combination of Debbie as director and community partners who really understood the value of a school library program and the inequity across the district of there not being a real centrally funded library program. As Boston moves toward equity, in general, school library access to these programs is a big part of that.”

This year, BPS will see 25 new libraries along with 30 new librarians, with funding to ensure an opening day collection of new culturally sustaining books. The investment will also support improvements to current library spaces, including new furniture.

The new budget will use a mix of federal pandemic recovery funds to buy new books and invest in technology, and BPS funds to pay for staff—ensuring a sustainable funding source for those positions. Most schools will eventually have their own space on campus, but some will partner with their nearby Boston Public Library branch.

“We have had a long relationship and collaboration with Boston Public Libraries,” says Phipps-Soeiro. “We want what they want, which is kids to have access to books and resources, so it’s really a gift to be able to work with them.”

Some have argued that funding could be used on other resources to increase literacy, from smaller classroom libraries to hiring reading tutors, but librarians say that’s missing the crucial role professional librarians play in classroom learning.

“I think the biggest thing that’s so important about having a certified librarian is that you’re teaching digital literacy skills and research skills,” says McBride. “We need our students to be discerning users of information and make sure they’re ready for college and careers. If you don’t have that person, you’re adding more work to a teacher.”

|

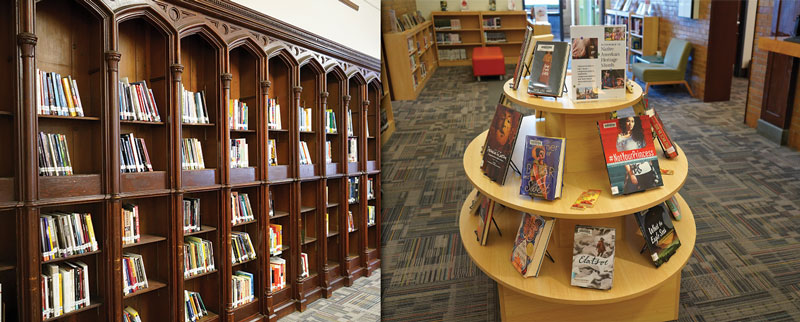

Recent displays at the Fenway High School library |

A goal of equitable literacy

The new investment is directly tied to Boston’s overall goal toward more equitable literacy for its students, which includes not only access to a librarian, but also a culturally affirming and complex collection of texts across grade levels and content areas.

“Providing these great, beautiful new collections allows students to have the agency to choose what they want to read and learn about,” says Froggatt. Assistant director of library services Felicia Humphries agrees, adding that libraries are also staffed to serve student—not teacher—interest.

The Lee K–8 School in Boston’s Dorchester neighborhood is one of the schools that received an infusion of funds this year. While students at Lee had access to a library space, the collection was woefully antiquated to meet the needs of the diverse student body of 550 students, a significant portion of whom are on the autism spectrum.

Treena Hogan had been a paraprofessional in Lee’s library. This year, she became the full-time librarian. Already, she’s purged the library of its outdated offerings and added a catalogue of nearly 4,000 new books thanks to the initiative. She says the library has quickly become a favorite for students—and not just because of the new collection.

“I remember a time when some of our students didn’t know we had a library, and some didn’t have access,” Hogan says. “We’re an inclusion school with all sorts of learners, so we worked on my schedule, and now if students can’t come to the library, the library can come to them.”

Lee principal Paul Kennedy says the new library now features a modern collection that reflects the cultures of the school’s community. It also shows that the city, as Kennedy puts it, is “putting our money where our mouth is” in its commitment toward a goal for equitable literacy for all its students.

“Libraries are usually last in line, but they are so crucial to our community and students,” says Kennedy. “For Boston to make such a large investment, it makes clear what our mission is around literacy in our schools and community.”

Hogan adds that the funding allowed them “to tie all these pieces together and create this awesome program to support our children’s literacy, culturally and academically.”

Recognizing the value of librarians

Boston’s investment in school libraries is more than just an increased budget. For years, certified school librarians have been evaluated separately from classroom teachers. But now, Boston is setting up a new model of evaluation that treats school librarians as instructors to better reflect their impact on student learning.

“In the past, if a school principal never used the school library, they didn’t know how to evaluate and grow their school librarians,” says Froggatt. “That mindset is really changing in Boston, and we’re working with the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education to grow it across the state.”

BPS is also supporting Hogan in other ways, including helping her earn her master’s in library studies. Library Services will also be working closely with local library programs to help create a pipeline for new applicants to get their school library credentials.

New librarians like Hogan will also be matched with a veteran BPS librarian as part of a new district-wide mentorship program to provide additional opportunities to gain expertise.

“It’s so helpful to bounce ideas off of other librarians, especially if you’re the only one at your school and just starting a new program and have questions,” says Fenway’s McBride, who will share her near decade of experience with new BPS librarians this year. “I already have a couple of new librarians paired with me, and helping guide them as they start to put together their collections is so exciting.”

As the library investment goes into effect, BPS will be closely measuring the impact of the initiative through a new data collection tool created by library team members to track statistics like the number of classes taught, the number of student visits, and community outreach. Library Services will also be launching a library advisory council later this year to gather feedback from stakeholders, including students, families, and community members.

All told, it’s an exciting time for the city, its libraries, and most importantly, its students.

“The fact that Boston is reinvesting in librarians is incredibly important for the kids of Boston and the kids of Massachusetts, because it’s walking the walk that libraries are important to a holistic and rich education that affects learning and kids’ love of learning,” says Phipps-Soeiro.

Former classroom teacher Andrew Bauld is a freelance writer covering education.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!