2018 School Spending Survey Report

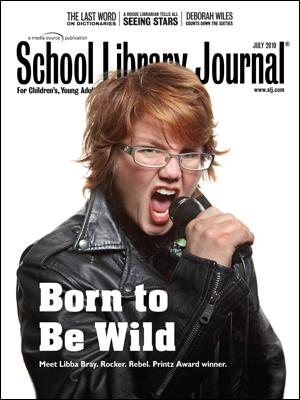

Born to Be Wild: Meet Libba Bray. Rocker. Rebel. Printz Award winner. Our July cover.

Photograph by Matt Carr.

One cold day last January Libba Bray decided to check out “Who Shot Rock & Roll,” a photographic exhibit at the Brooklyn Museum in New York. No surprise there. This is a woman who spent a good amount of her teenage years dancing and singing into her hairbrush, hoping to become the next Jimmy Page or Robert Plant. So it was fitting that as Joey Ramone stared down from a poster, Bray’s phone rang and she suddenly learned that her latest novel, Going Bovine (Delacorte, 2009), had won the Michael L. Printz Award as the year’s most distinguished title for teens. For a moment, at least, as the members of the award committee offered their congratulations, the universe’s stars seemed in perfect alignment. Since the publication of A Great and Terrible Beauty in 2003, Bray has captured the imaginations and loyalties of a host of teen readers. This initial entry in a trilogy—which includes Rebel Angels (2005) and The Sweet Far Thing (2007, all Delacorte)—introduces Gemma Doyle, a young girl living in the repressive Victorian Era who discovers she can enter a spirit world that holds power and danger. Going Bovine departs from these historical Gothic novels and Bray’s chilling short stories, such as “Bad Things” and “Nowhere Is Safe.” Fueled by Don Quixote and led by the ethereal Dulcie, a modern counterpart to Cervantes’s Dulcinea (with pink wings, no less), Bovine’s hero, 16-year-old Cameron Smith, a victim of Creutzfeldt-Jakob (aka mad cow) disease, begins a journey of epic proportions. Cameron and his video-game-addicted dwarf friend Gonzo set out to connect certain random incidents (particularly those described in tabloids); find the parallel world of Dr. X, who is the only hope for curing this terminal disease; and, in the process, save the universe. These days the 46-year-old author lives in Brooklyn with her husband, Barry, their 11-year-old son, and two cats, Squeek and Cocoa. Although Bray believes that Tex-Mex should be a required food group, on a more serious note, she vigorously defends the need for strong libraries in her speeches and on her blog. In turn, librarians vigorously defend the need for strong books—like Going Bovine. Tell me about your teen years, growing up in Denton, TX. I was a big goofball. And a smart-ass. And rebellious. I occupied that space that a lot of teenagers—and especially teenage girls—understand, which is a push-pull between wanting to be liked and being a pleaser and needing to form my own identity. I was also a dichotomy. I was serious about school and understood that an education was important. I did like to learn even if I was sometimes an idiot about it. I really applied myself in the classes I liked, i.e., English, writing, drama, and art. And the classes I didn’t care so much about—like math—I didn’t put forth much effort. How about science? I took physics, which I loved, but didn’t have the math background for it. It was a sixth-period class and one day I skipped. I went to the bookstore, and who should come up but my physics teacher, Mrs. Gilbert, God bless her. Now I had ditched her class, and I’m clearly not throwing up or anything. I said, “Hi, Mrs. Gilbert.” “Hello, Libba.” And then she said: “What do you want to do with your life?” “Oh, I don’t know. I think something artsy, maybe be a filmmaker.” She looked at me and said, “I’ll bet you’ll be great with that.” And then she put a hand on my shoulder: “Honey, let’s face it. You’ll never be a nuclear physicist. Why don’t you just drop my class before you fail it entirely?” Little did she know that one day you’d write an award-winning book that addresses string theory and the physics of time and space. Well, yes, but I felt dumb as a box of rocks trying to learn that stuff. Did you get into a lot of trouble as a kid? I got up to my share of no good. I had a wild friend who lived in Dallas. Jeanie. Her mother said we had the perfect kind of relationship: Jeanie got us into trouble and I got us out. And that was a push-pull as well. I think for women there’s always that element of push-pull. I agree. I think it’s because women are more tribal. There’s that sense of needing the community. We are always our mother’s daughters, wanting to please our mothers, not wanting to be like our mothers, and inevitably being like our mothers. Were there any early hints as to your future career? I was always interested in the theater and very much a dreamer. I lived at the community theater, building sets, acting in plays, and goofing off with my friends. I loved it. That was a great place to be. Weren’t you a playwright for a while? Yes, but not a very good one. I heard that after you moved to New York in 1990, you worked for a book packager. I did. I wrote three books for them. The first was Kari: Sweet Sixteen #3 [Harper, 2000]; the second was The Nine Hour Date [Bantam, 2001] written under the pseudonym Emma Henry. The last one was for a series that was never published. What did you learn from that experience? It was a great experience. I call it boot camp for writing because you learn that you can outline, break something down into scenes, and write to that outline. I’ve never done it since, but in theory you can do it and you can write a novel in two months. It was good discipline for somebody who didn’t have any idea about how to write a book, because it forced me to think about story and not get lost in the writing. My first editor was Ann Brashares. She was very generous and good about helping me keep focused. I also realized that writing is a job, that someone is paying you to write a book, and you better show up and put your fingers on the keys. I’m really surprised you don’t do outlines. I just assumed that Going Bovine was the product of a flowchart from hell. You would think. Unfortunately, that flowchart lived in my brain, which meant that there were times when the keys were in the fridge and the milk on the counter. I wish I had a better way of writing than through chaos theory, but I swear to you that’s the way my brain works. And that’s why, for me, revision is so important. I think of it as active re-imagining. You’re very good at dropping hints for the reader, as though you know precisely where the story is going. I don’t to begin with. So often I’ll find myself in that proverbial corner with a just-painted floor, going, “Oh, there’s the door. How am I going to get to that door?” But I trust my unconscious and the connections keep coming through. I rewrite and rewrite and rewrite and start pulling the pieces together. For me that part is fun, like jazz. My synapses are going wild and I’m thinking, “Oh, now I get it! I need to bring in Virgil here or make a reference to Don Quixote.” It’s like Jackson Pollack slapping paint on a canvas and waiting to see what’s going to emerge. Is Cameron’s search for randomness a case of art imitating life? Pretty much. Holly Black, who is a really disciplined and linear writer (I call her my guru of structure), was helping me with my new book and asked why Going Bovine was so much easier for me to write. I told her it was because that’s the way my brain works. The novel has a loose framework in that it is a road trip, so the narrative is inherent; you are always moving forward because it is a journey. But everything branches off from that journey in an episodic, circular fashion, always looping back to what happens in the beginning. Was writing Going Bovine your way of returning to the 21st century after the “Gemma Doyle” trilogy? I wrote Going Bovine between books two and three of the trilogy. I wrote it for Cynthia Leitch Smith, who had invited me to a wonderful writing festival in Austin, TX. But I was late submitting Rebel Angels. I was supposed to turn in a complete manuscript to Cynthia by May 1 [2005], and in February I thought, “Oh, Lord. What have I gotten myself into?” So I called her up and said, “Cyn, can I have like a partial?” And she said, “No, Ma’am. Beginning, middle, and end turned in by May 1. I’ll see you then.” As I jokingly say, “Miss Cyn does not play.” And, thank goodness, because I needed that push. I had this idea for Going Bovine in my head for three years, but I just didn’t know what it was going to be about. But keeping it in a drawer for three years gave it plenty of percolation time. Now that you’ve finished writing the novel, would you say it’s about life or death? Yes. Are today’s adults, like the grown-ups in your story, trying to build a Church of Everlasting Satisfaction and Snack ‘N’ Bowl for their kids, where there are no losers, only winners, and everyone is gratified all the time? I’ve thought about this a lot in terms of being a parent. You want to protect your children, yet you want to be realistic, and sometimes that’s a struggle. I’m often concerned about being too critical. My mother is an English teacher, so that red pen is never far from her hand. In her generation, you showed love by criticizing your children and constantly letting them know how they could be better. So I didn’t want to be that way, but understood it also has a purpose. How else have your parents influenced you? As the daughter of a minister and an English teacher, of course I see the world in terms of symbolism. There’s a New American way of thinking that I call the Unrealistic Happiness. When my son went to preschool, he could not bring any superhero action figures because they held unattainable powers. The thinking was that such toys would somehow make the children feel less than. This culture tries to negate aggression and unhappy feelings. Of course, we’re in the business of civilizing our children; that’s our job. But we have all these uncomfortable, icky feelings that we have to work through as human beings. To repress them is just not honest. There’s an awful lot of pressure on kids these days and a lot of life they have to figure out themselves. Certainly one of the valuable experiences of my life was living through a horrible disfiguring car accident because no one could protect me from that. Parents can’t make everything right. That’s not the way life is. The true measure of a person is being able to get back up. When there’s a moment of crisis, your mother’s not always there. You’re alone. As one friend says, “The hand you hold the longest is your own.” There’s an existential condition, a loneliness, we fight against all our lives. On occasion, when we read a book or see a movie or piece of art or have an epiphany, we come face to face with that. And it’s hard, painful, and necessary. You don’t have to live there, but you have to tear down all the nuggets and get to the truth. We can’t shop it away or blog it away or create crazy elaborate constructions to try and avoid that truth. And it’s really hard, but it’s what it means to be human. So tell me, what was it like walking the streets of New York City dressed like a Holstein cow to promote Going Bovine? I was walking from Random House to Times Square talking to my husband, and I noticed people were staring. I’m thinking: “What’s their problem?” And then I remember I’m in a cow suit. The cow and I had become one. I would think that cow suit would allow some anonymity. As it happened, I had blogged about shooting the video, and this woman and her daughter, Katie, were in town and they recognized me. Apparently I’m born for the cow suit. You have an enormous online presence. Do you think authors need to blog? A Great and Terrible Beauty came out in December, at the end of 2003, and I started blogging then. Certainly publishers would like for you to blog and readers really enjoy the chance to communicate with you in that way, but if it doesn’t suit who you are then it’s probably not a good idea. I’m also a mother, so I’m anchored here. And because writing is an isolated experience, being on the Internet is a way to be able to communicate, and I really enjoy that. Music has always been a part of your life, and now you’re the lead singer of a band called Tiger Beat. How did that come about? The band is the brainchild of Dan Ehrenhaft [guitar] and Barney Miller [drums]. Dan wanted a YA version of the Rock Bottom Remainders. Dan recruited Natalie Standiford [bass] and then, after a night at a karaoke bar, he asked me. We get together in a crummy old rehearsal space in Manhattan. It’s fun being part of a group, but Tiger Beat is just plain joy. You seem to be part of a very tight group of young adult authors. A lot of the credit for that goes to David Levithan. A couple of years ago he started YA Author Drink Night. So once a month authors would get together and hang out at this one bar. It is great fun and a way to foster community because, as I said, it is a lonely thing to write. When you’re in the trenches and stuck on something, you can turn to another author and say, “Ya know…,” and she will say, “Oh, honey, I do know. I’m moving away all the sharp objects and here’s a chocolate thing.” There is a closeness. I think some of that is because writing for teens has been marginalized for so long. We support each other and read and enjoy one another’s work. How did you feel when you found out you’d won the Printz? Wow. What a rush. This was the book I had to write even though part of me thought it would be career suicide. To have someone validate the book that was a piece of my soul was lovely. The Printz certainly makes up for the mean girls who stole my pet rock collection in sixth grade. The mean girls may have my pet rocks, but I’m not bowed. Former classroom teacher and school librarian Betty Carter reviews for The Horn Book and contributes to the online database Books and Authors.RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!