2018 School Spending Survey Report

Alice Hoffman on "Nightbird" | "I Write the Book I Want to Read."

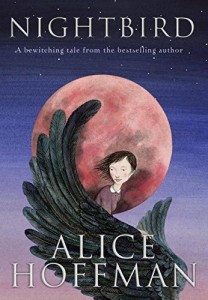

In an interview, Alice Hoffman talks about her new middle grade novel, "Nightbird," and the power of fairy tales.

In Nightbird (Wendy Lamb/Random House, March 2015; Gr 5-8), Alice Hoffman explores the impact that keeping a secret has on 12-year-old Twig. The girl's brother, James, bears the burden of a 200-year-old curse placed on his family: all male children will be born with wings. When Twig confides in a new neighbor, tectonic shifts begin to occur in their small Massachusetts town. Here Hoffman speaks of the power of fairy tales and the desire to write for the young reader that lives within her. Nightbird shares a melding of magic and realism that's present in your books for young adults, Green Angel and Aquamarine, and your adult novels. What is it about that combination that compels you as a writer? My childhood reading was fairy tales, and even though they were magical, they felt the most real. In terms of what was happening emotionally and psychologically, even if the story was about a beast or a rose that wouldn't die, there were truths there. That the magical and the real exist side by side makes sense to me. I always think of myself as a 12-year-old reader…[and] write the book that I want to read. Where did the idea of Nightbird come from? This story is about the isolation that comes from secrets. I think many kids know about family secrets, and they know they're not supposed to discuss them. What was the inspiration of James's curse? I thought of the Minotaur—because of his birthright, he's confined to this half-man, half-creature body. It's that idea of the sins of the father visited upon the son, isn't it? The idea of a family curse, especially one that isn’t talked about, is ancient, whether from father to son or mother to daughter. It's like the secret of the nursery: you know it even when you don't know it. Also, the monster in the family is a common mythological situation. Nightbird came to me as the story of a “monster’s” sister—one who knows that her sibling is not a monster. How you appear on the outside isn't necessarily how you are inside. Kids at this age intrinsically know that. We loved the portrayal of the “Gossip Group”—the men who hang out at the general store, discussing everything and everyone. Even though they're looking to catch the mysterious nighttime monster that’s been reported around town, they're not villainous. There is the sense in small towns that everyone knows everyone, but they're not out to do anything bad; they're out to protect their neighbors. It appears that Twig's mother moved to New York to escape the fact that everyone knows everyone's business. Yes, but you carry your legacy with you. That's what happened to her. I thought of this as a mother-daughter book…. It's about understanding your parent a little bit [better]. You can never know your mother when she was younger. Twig’s mother, too, doesn't really know Twig. In the beginning of the book, Twig falls from a tree in her attempt to spy on the new neighbors—the Halls. Does the tree represent the Tree of Knowledge, in the sense that it’s the end of the girl going along as the innocent party to her mother’s secrecy? If Twig hadn't fallen—and everything it means in terms of apples and apple trees—she wouldn't have made the connections she does. They make her more human. That's what books were to me. I feel that they'll never die because as the reader you have to be the imaginer. I don't think any other art form [requires] that. Twig's friendship with Julia Hall transforms her, doesn't it, in the same way that James’s love of Agate Hall transforms him. They move from isolation to connections, from fear to faith in ways that their mother cannot. Do you think children have the power to inspire that kind of faith in their parents? I do. I think you learn a lot from your children and they take you places you wouldn't necessarily have gone. Friendships also bring you outside of your family—much like reading a book, in a way. It's an important step for Twig. You also have a conservationist theme in here. Did that evolve naturally from the plot? Or was it part of your inspiration for the book? It really did evolve. It wasn't there at the beginning. I realized a lot of what's going on in this town, is the feeling that people love it. They want to protect it, which is something they have in common. Except for an outsider [a real estate developer] who doesn't think of the place that way. You nicely thread the legend of Johnny Appleseed in there, too. Are we in danger of losing that legend? I'm a little obsessed with Johnny Appleseed. He's such an interesting character. I wrote about him once in an anthology of stories set in Massachusetts [The Red Garden]. He's the original hippie and conservationist. He was a wild, interesting character. You published your first book when you were 22. What writing advice would you give to aspiring authors? I think the most important thing is to be a reader. It's a very small step from being a reader to being a writer. You become a writer when there's a book you want to read that hasn't been written.

In Nightbird (Wendy Lamb/Random House, March 2015; Gr 5-8), Alice Hoffman explores the impact that keeping a secret has on 12-year-old Twig. The girl's brother, James, bears the burden of a 200-year-old curse placed on his family: all male children will be born with wings. When Twig confides in a new neighbor, tectonic shifts begin to occur in their small Massachusetts town. Here Hoffman speaks of the power of fairy tales and the desire to write for the young reader that lives within her. Nightbird shares a melding of magic and realism that's present in your books for young adults, Green Angel and Aquamarine, and your adult novels. What is it about that combination that compels you as a writer? My childhood reading was fairy tales, and even though they were magical, they felt the most real. In terms of what was happening emotionally and psychologically, even if the story was about a beast or a rose that wouldn't die, there were truths there. That the magical and the real exist side by side makes sense to me. I always think of myself as a 12-year-old reader…[and] write the book that I want to read. Where did the idea of Nightbird come from? This story is about the isolation that comes from secrets. I think many kids know about family secrets, and they know they're not supposed to discuss them. What was the inspiration of James's curse? I thought of the Minotaur—because of his birthright, he's confined to this half-man, half-creature body. It's that idea of the sins of the father visited upon the son, isn't it? The idea of a family curse, especially one that isn’t talked about, is ancient, whether from father to son or mother to daughter. It's like the secret of the nursery: you know it even when you don't know it. Also, the monster in the family is a common mythological situation. Nightbird came to me as the story of a “monster’s” sister—one who knows that her sibling is not a monster. How you appear on the outside isn't necessarily how you are inside. Kids at this age intrinsically know that. We loved the portrayal of the “Gossip Group”—the men who hang out at the general store, discussing everything and everyone. Even though they're looking to catch the mysterious nighttime monster that’s been reported around town, they're not villainous. There is the sense in small towns that everyone knows everyone, but they're not out to do anything bad; they're out to protect their neighbors. It appears that Twig's mother moved to New York to escape the fact that everyone knows everyone's business. Yes, but you carry your legacy with you. That's what happened to her. I thought of this as a mother-daughter book…. It's about understanding your parent a little bit [better]. You can never know your mother when she was younger. Twig’s mother, too, doesn't really know Twig. In the beginning of the book, Twig falls from a tree in her attempt to spy on the new neighbors—the Halls. Does the tree represent the Tree of Knowledge, in the sense that it’s the end of the girl going along as the innocent party to her mother’s secrecy? If Twig hadn't fallen—and everything it means in terms of apples and apple trees—she wouldn't have made the connections she does. They make her more human. That's what books were to me. I feel that they'll never die because as the reader you have to be the imaginer. I don't think any other art form [requires] that. Twig's friendship with Julia Hall transforms her, doesn't it, in the same way that James’s love of Agate Hall transforms him. They move from isolation to connections, from fear to faith in ways that their mother cannot. Do you think children have the power to inspire that kind of faith in their parents? I do. I think you learn a lot from your children and they take you places you wouldn't necessarily have gone. Friendships also bring you outside of your family—much like reading a book, in a way. It's an important step for Twig. You also have a conservationist theme in here. Did that evolve naturally from the plot? Or was it part of your inspiration for the book? It really did evolve. It wasn't there at the beginning. I realized a lot of what's going on in this town, is the feeling that people love it. They want to protect it, which is something they have in common. Except for an outsider [a real estate developer] who doesn't think of the place that way. You nicely thread the legend of Johnny Appleseed in there, too. Are we in danger of losing that legend? I'm a little obsessed with Johnny Appleseed. He's such an interesting character. I wrote about him once in an anthology of stories set in Massachusetts [The Red Garden]. He's the original hippie and conservationist. He was a wild, interesting character. You published your first book when you were 22. What writing advice would you give to aspiring authors? I think the most important thing is to be a reader. It's a very small step from being a reader to being a writer. You become a writer when there's a book you want to read that hasn't been written. RELATED

RECOMMENDED

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

CAREERS

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Dodie Ownes

This is what all my favorite writers say - I think you'll find threads of this sort of relationship with characters and - Writing what I want to read - in titles from Andrew Smith, Marissa Meyer, Barry Lyga, Marie Lu.. Fantastic interview.Posted : Mar 25, 2015 08:39