Advocate This, Not That!

Illustration by James Yang

“A university is just a group of buildings gathered around a library,” wrote the historian and novelist Shelby Foote. Consider a corollary to this quote—a school is just a group of buildings gathered around a library—and whether it aptly describes how important your school library is to the overall function of your institution.

Too often, school libraries are seen as peripheral, not central, to teaching and learning. We can speak to parents, teachers, and principals about the value of our programs and services, but the decisions about how to best allocate funds are often made at the district level. When money gets tight, those programs with the greatest impact on the highest priorities are valued the most. After decades of chronic underfunding, the situation is especially dire here in California, where I live and work. Many of the typical advocacy talking points simply don’t cut it anymore.

In my role as lead coordinator of library media services at the San Diego County Office of Education, I regularly work with schools and districts to improve their services. In California, County Offices of Education are an intermediary level between the California Department of Education and local school districts, providing support and oversight. My work has given me a big-picture view of our educational system. It has also helped me realize that we need to reframe key school library elements to bring into better focus our meaningful contributions to four important system-level priorities.

Equity and access, not reading. More than half of California students did not meet or exceed the reading standards in 2016. Closing this achievement gap is a vexing problem, and there is no shortage of resources being applied to remedy the situation. Of course, I suspect the real solution has less to do with what happens in the classroom than with what happens—or doesn’t happen—outside. To wit, students in the 90th percentile read 200 times more outside of school than those in the 10th. In other words, 90th-percentile kids read more in two days than students in the 10th read all year.

My own experiences as a classroom teacher confirmed this long before I ever read the research. Parents of 90th-percentile readers routinely told me that their children read for a couple of hours a day, that they needed to have books and/or flashlights taken away from them at bedtime, and that they needed more book recommendations because they had exhausted all of my previous ones. Those in the 10th percentile should have been reading a couple of hours a day, too. You can’t give that kind of homework assignment to any students, however, let alone struggling ones. Instead, you motivate them to do it freely and voluntarily.

But what good is it to motivate students to read if they don’t have access to books? Studies show that students with 500 books in their homes complete three more years of schooling than their peers, that each book up to that number has a measurable impact on academic achievement, and that those books have a greater effect on socioeconomically disadvantaged children. While the average home has about 100 books, two-thirds of low-income homes have none. Increasingly, those homes are clustered in poor neighborhoods that have become veritable book deserts. It’s time to honestly examine the myriad ways that our school system denies access to students who need it the most. Curriculum and instruction, not information literacy. Collaboration is one of two ways that we can powerfully impact curriculum, instruction, and assessment. Too often, what passes for collaboration is merely coordination (juggling schedules and resources) or cooperation (teaching skills in isolation from classroom learning). Genuine collaboration is when the classroom teacher and the school librarian share in the planning, teaching, and assessment of a lesson—typically a research project in which students develop, articulate, and pursue a line of inquiry by exploring multiple sources. Ideally, this kind of integrated instruction would be so ubiquitous that it would be the rule rather than the exception. The school librarian would collaborate with every teacher in the school at least once during the year.

Curriculum and instruction, not information literacy. Collaboration is one of two ways that we can powerfully impact curriculum, instruction, and assessment. Too often, what passes for collaboration is merely coordination (juggling schedules and resources) or cooperation (teaching skills in isolation from classroom learning). Genuine collaboration is when the classroom teacher and the school librarian share in the planning, teaching, and assessment of a lesson—typically a research project in which students develop, articulate, and pursue a line of inquiry by exploring multiple sources. Ideally, this kind of integrated instruction would be so ubiquitous that it would be the rule rather than the exception. The school librarian would collaborate with every teacher in the school at least once during the year.

This model of information literacy has been around for decades and has been described thoroughly in the research, but it only rarely and fleetingly exists in the real world. It will require significant organizational change to bring it about and scale it up across a district. While librarians must be change agents in that process, they can’t evolve into that role without administrative support.

We have a second powerful tool in our skill set that can impact curriculum, instruction, and assessment: curation. As schools increasingly supplement or replace textbooks with open, free, and low-cost proprietary resources (such as databases, ebooks, and library books), school librarians become invaluable not only because they curate these resources, but more importantly because they teach students and staff how to navigate them. There is also an opportunity to shift money from the textbook budget to the library one. If you can maintain the level of quality in instructional materials, and if you can shift to innovative pedagogy, then you will spend the same amount of money. You can also upgrade your library and tech programs while empowering your classroom teachers to take greater ownership of the curriculum.

College and career readiness, not ed tech. Information literacy and educational technology are so intertwined that it’s often hard to tell where one ends and the other begins. They both have lots of cachet with administration, but it’s quite clear at this point that the digital age in and of itself will not revolutionize education. While college and career readiness are the endgame, it all starts with student engagement. Students can have ineffective teachers and poor textbooks, but if they are engaged by a particular topic, they can persevere and thrive.

Engagement is especially crucial for information literacy, because the school library is the only classroom that promises complete academic freedom: Here you may learn about whatever you wish. Personalized learning has become trendy recently, but we’ve always been about helping students immerse themselves in information and, more recently, in experiential learning such as maker spaces and learning labs.

Maker spaces are an outgrowth of the STEM movement, and inasmuch as they incorporate the inquiry process, design thinking, content creation, and ed tech, they are squarely in librarians’ wheelhouse, too. Learning labs, established in many public libraries and museums across the country, leverage a body of research known as Connected Learning in order to connect youth interests, peer culture, and academic content to digital media such as recording studios, film and video, gaming, graphic design, podcasting, and coding. It’s all supported by a series of progressively immersive learning environments that allow young people to discover and develop their talents. Schools don’t usually have the financial or community resources to pull off learning labs on a grand scale similar to public libraries and museums, but school librarians can still leverage their core principles. In one way, we are better equipped to capitalize on them than our public library colleagues, because most students have greater access to school libraries (if their school has one, of course).

It’s easy to remember those progressively immersive learning environments with the acronym HOMAGO (Hanging Out, Messing Around, Geeking Out). Helping students transition to that critical third Geeking Out phase—where they voluntarily engage in deep learning in a more formal academic setting—can be challenging. School librarians are already doing much of the Hanging Out and Messing Around work, albeit in a haphazard, patchwork fashion. Now we need to create order from the chaos. Perhaps there’s an opportunity to collaborate with school counselors, career technical education teachers, and others to articulate a clearer pathway from school library programming to Geeking Out. Ultimately, the school library can serve as a route to more pathways, propelling students from engagement to purpose.

Universal Design for Learning, not collection development. The Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) is an integrated, comprehensive framework designed to help all students succeed academically, socially, and behaviorally. The idea behind MTSS is to intentionally realign the various systems of support so that student needs can be quickly identified and matched with an appropriate one. While Response to Instruction and Intervention (RTI2) and Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) are the two most obvious models (and indeed MTSS is most often seen as an outgrowth of them), the true power of MTSS is that it leverages every existing support into a cohesive whole.

Universal Design for Learning, not collection development. The Multi-Tiered System of Supports (MTSS) is an integrated, comprehensive framework designed to help all students succeed academically, socially, and behaviorally. The idea behind MTSS is to intentionally realign the various systems of support so that student needs can be quickly identified and matched with an appropriate one. While Response to Instruction and Intervention (RTI2) and Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports (PBIS) are the two most obvious models (and indeed MTSS is most often seen as an outgrowth of them), the true power of MTSS is that it leverages every existing support into a cohesive whole.

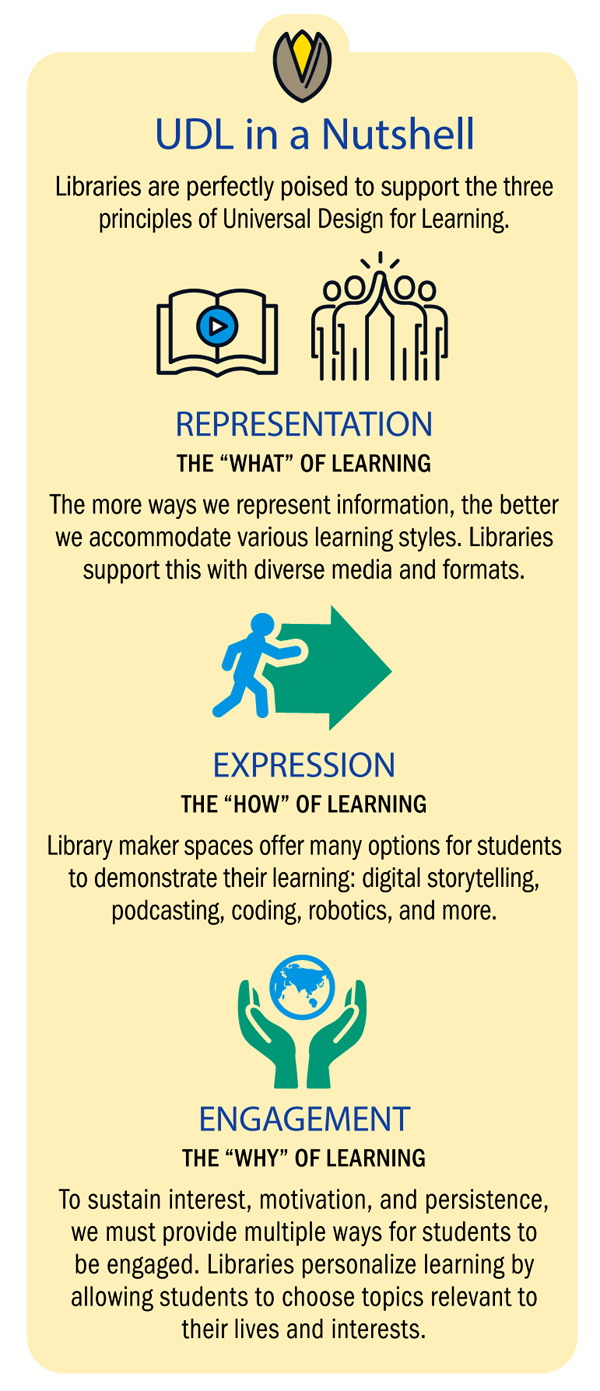

Our primary contribution to MTSS has to do with Universal Design for Learning (UDL). Neuroscience has discovered that the way we each learn is as unique as our fingerprints. The rationale for UDL is to create curriculum, instruction, and assessment that will meet the learning needs of our diverse student populations. The core principles are threefold—representation, expression, and engagement (see chart).

The more ways we can represent information, the better we accommodate various learning styles. School library collections typically include diverse media and formats: multiple books on a single topic with different reading levels and different design aesthetics; interactive databases with text-to-speech and translation features; streaming video and audio; models, manipulatives, and puppets; curated websites and apps; and so much more. In short, we are a veritable goldmine for representation—and expression.

The more ways we allow students to express what they know and what they can do, the more authentic our assessment will be. Once again, a school library—especially one with a maker space or a makeshift learning lab—offers a multitude of options for how students can demonstrate their learning: digital storytelling, podcasting, coding, robotics, arts and crafts, graphic design, and gaming. They can create, remix, and share information with innumerable technology tools. They can work collaboratively in project-based learning groups or individually with personalized learning goals.

If we properly allow for multiple means of representation and expression, engagement will naturally follow. But we can enhance this by allowing for student choice in assignments. Since our collaborative lessons tend to revolve around research that requires students to choose a line of inquiry, we are primed and ready for this assignment. Librarians are being asked to collaborate with teachers around multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement. Is this not our raison d’être? UDL seems like one of the best things that could have happened to school libraries.

Traditionally, the school library has represented reading, learning, and knowledge. Indeed, Albert Einstein famously said, “The only thing you absolutely have to know is the location of the library.” The school library is poised at the nexus of two of our most glorious democratic institutions: the public education system and the public library system. It inherits a wonderful legacy from each—and a shared responsibility: to foster an informed and engaged citizenry. Increasingly, the school library also represents equity, access, and opportunity. If your school is not a group of buildings gathered around a library, at least metaphorically, then I have made my best argument for why it should be. If we are going to change the status quo—if the school library is to ever fulfill its promise—then it must be transformed from the top down as much as from the bottom up. It can’t only be a grassroots movement. If budgets really are statements of values and strategic vision, and if schools and districts time and again spend large sums of money on lower-impact priorities with lackluster results, especially for our most vulnerable students, then it’s high time for a change—we are the ones to demand it.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Sheila Miller

Thank you for sharing this perspective. Working in a school district which is facing huge cuts in the coming year, this gives our positions a purpose. Unfortunately, the leadership does not share the same views, although attempting to bring this district into a 21 Century academic learning experience. Your views of the importance of the library support the movement of the library as the hub of learning. Now to get administration and teaching staff to understand and embrace the culture of library usage, is the challenge for me.Posted : Mar 07, 2018 09:15

Jackie Rivera

What an insightful article! Thank you for writing it. Now let’s hope all school take heed.Posted : Jan 19, 2018 01:11

Laura Hidalgo

This is an incredibly well-written article, which I hope will gain attention in the larger school community (beyond the library!). Thank you for giving us this powerful tool to share with teachers and administrators.Posted : Jan 14, 2018 12:50

Casey Bowlan

Great article, Jonathan! I will be sharing with the administrators and librarians I help.Posted : Jan 03, 2018 10:12