Pronouncing Kids’ Names Correctly Matters. Here’s How to Get it Right.

Mispronouncing a student’s name can have a significant negative impact. Getting it right sends a better, affirming message.

Related Article"21 Books About Children and Their Names" "A Student Takes Pride in His Name That Everyone Mispronounces" |

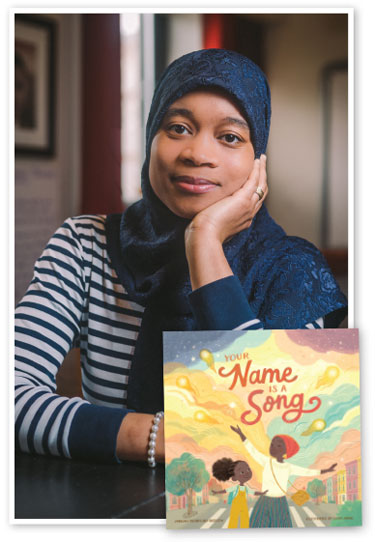

For some students, returning to school with new teachers and classmates can be uniquely difficult. “As a Black kid, I had that experience of people just mispronouncing my name,” says author and educator Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow. She got everything from Jamal to Jamalia to Janelle. One teacher called her Jamil. “I remember always going, ‘Ah. Just add an ah.’ ” Meanwhile, she thought, “My name is literally three syllables.”

When she became a high school teacher, Thompkins-Bigelow saw other teachers, especially white educators, “dismiss the importance of” getting names right. One student at her school had a “musical” name that was unusual. “You could tell it was very carefully crafted,” she says. But few educators took the time to learn the student’s name, or they tried once and gave up, using a nickname instead.

Thompkins-Bigelow was reminded what “Jamil” had felt like. “I knew it needed to be addressed,” she says, noting that her brother’s name was also “terribly butchered” when he was young.

Her book Your Name Is a Song was born. In that tale, Thompkins-Bigelow’s protagonist, Kora-Jalimuso, describes how her teacher bungles pronouncing her name. “It got stuck in her mouth,” she tells her mother.

|

Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow |

Your Name Is a Song is one of many children’s picture and chapter books that celebrate and affirm names. And in back-to-school season, it’s especially important for educators to learn to get all children’s names right.

While mispronouncing a student’s name may seem minor to some adults, it can have a significant impact, says Christine Yeh, professor at the University of San Francisco School of Education.

“It sends a message that they are ‘othered’ or don’t belong in this society,” says Yeh. Subsequent feelings of invisibility, anxiety, resentment, shame, and humiliation can lead to social and educational disengagement, she adds.

There’s a better message to send. Adults who work with children can make them feel like “valued members of the community” by getting names right, Yeh says. They can sign the My Name, My Identity pledge and learn tips for remembering and pronouncing students’ names.

For example, adults can say, “I really want to be able to pronounce your name the way you want to hear it,” or “I’d love to say your name the way your family says it. Can you help me learn to say it?”

And they can go further, using name books to create a climate where everyone’s name is valued. Yeh says all types of educators, at all levels, are in a unique position to send children the message that they matter “and that their histories are important.”

An unfair burden

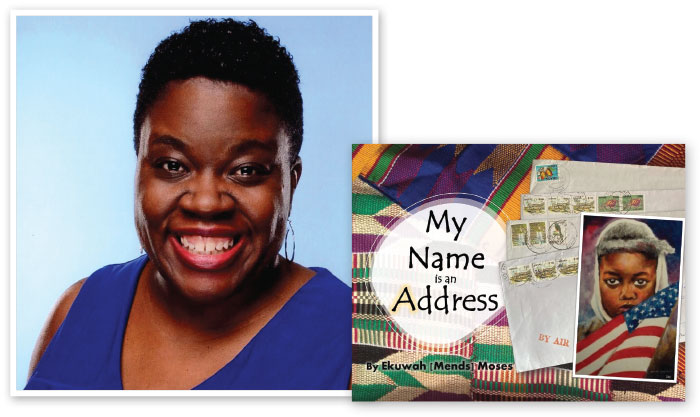

In her book My Name Is an Address, Ekuwah Mends Moses, the child of an African American mother and a father who immigrated from Ghana, explores her name and her family history along the way.

“Did you know that a name includes history, geography, and migration?” she writes. “Language, culture, and heritage are also linked to a person’s name.” The bottom line: Every name tells a story, and everyone’s story merits telling, even though kids often receive a different message.

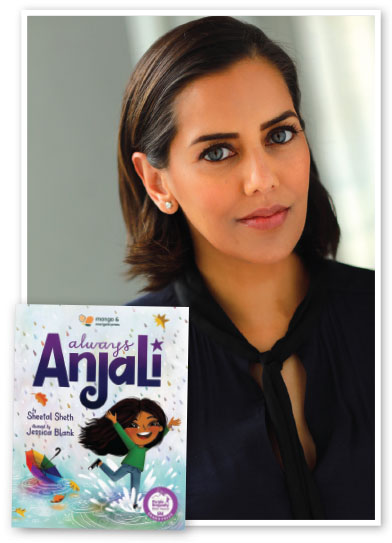

Sheetal Sheth has been an actor since the 1990s, “before brown was cool,” she says. “I cannot tell you how many people suggested or highly recommended that I change my name.” Sheth, who is Indian American, watched it happen to other aspiring actors of color and Jewish ones as well. Sheth kept her name and believes she lost out on roles as a result.

When she went to a bookstore to start building her first baby’s library, she realized, “Oh my god. These are the same books I had when I was growing up.” The handful of newer ones that offered more representation “felt very tokenized,” she says. “It ends up being like, I’ve got the Diwali book, I’ve got the Eid book, I’ve got the Lunar New Year book.”

That prompted her to write Always Anjali, the tale of a seven-year-old who plays instruments and sports, has dinner with her parents, and goes to school. Protagonist Anjali can’t spot her name amid a souvenir license plate display, and when a classmate sings a mocking song about her name, she contemplates changing it.

Publishing has changed a bit since Sheth was shopping Always Anjali, released in 2018. But some of the notes she got back from editors on her pitch “[were] either whitewashing the story, or they would say, ‘Well, this doesn’t feel Indian enough.’”

Sheth says she wanted to produce a slice-of-life story where “culture isn’t the narrative.” She wondered, “Why can’t you do a story about kids, and the family just happens to be Indian? The dominant white culture gets to do that.”

|

Ekuwah Mends Moses |

Now, when she reads Always Anjali at schools, Sheth asks students to raise their hand if they’ve ever had someone mispronounce their name, misspell their name, or give them a nickname they don’t like.

Almost all hands go up. “It’s universal,” she says.

At the same time, the children who take time to approach her afterward and share that their teachers and friends mispronounce their name are often kids of color. “It shouldn’t be on them” to correct and guide teachers, Sheth says. But at the same time, they have to be equipped to deal with the world they live in. “You get to the point where you [feel like you] can’t correct it anymore,” Sheth says, but she encourages kids not to give up. She’ll tell them, “You can, absolutely. Let’s do it right now.”

Sheth is walking a line familiar to those who think deeply about this issue: how to support children in standing up for their names without placing on them the burden to address the bias behind others’ unwillingness to try mastering certain names.

Educators can relieve students of that burden. Thompkins-Bigelow says, “When that name gets stuck in your mouth as a teacher, you have to just say it—‘I’m not getting your name right’—and not in a jokey way, like, ‘This is funny I can’t do it.’” She recommends saying, “Could you repeat that or break it up?” and includes an important addition: the word sorry. Otherwise, Thompkins-Bigelow says, you’re asking children to do all the emotional work, to take the discomfort upon themselves.

In Your Name Is a Song, the teacher eventually shows initiative, asking, “Could we hear your [name] song again?” Then she sings Kora-Jalimuso’s name back.

“It’s important to tell kids, ‘You may have to self-advocate, but at the same time, it’s not fair,’” Thompkins-Bigelow says. She advises educators to say, “I’m sorry I’m making this a difficult situation for you, but I want to do the extra work so that for the rest of the year you are not always annoyed or feeling diminished in some way.” Because that’s what she saw in the teenagers she taught whose names were mispronounced: irritation on the one hand, and a defeated acceptance on the other.

When a fictional character like Kora-Jalimuso engages in the process of insisting on respect for her name, it helps young people feel more comfortable clarifying the pronunciation of their own—sometimes multiple times.

Juana Martinez-Neal wrote Alma and How She Got Her Name to tell the story of her relatives and how they passed on their names. But she also wrote it thinking of her childhood in Peru with “a harsh, old-fashioned name” that others perpetually replaced with nicknames.

“Everyone felt it was too big and too strong for this tiny little thing,” she says. When her class graduated from high school, students were given a name necklace. She remembers filling in the boxes on the form with J-u-a-n-a, full stop. A well-intentioned parent volunteer changed it to “Juanita.”

|

Sheetal Sheth |

Now a parent in Connecticut, Martinez-Neal has devised a way to get things right with her daughter’s teachers. “Every single year, we send a recording of how to pronounce her name, because we get ahead of the game.”

Martinez-Neal repeats and spells out her own name so often in the United States that when she traveled to Peru, “They asked for my name, and I said in Spanish, ‘Juana, J-u-a-n-a.’ And the girl looked at me like, ‘Why are you telling me that?’”

Opportunity for empowerment

Yangsook Choi points to this phenomenon as a key experience of early-stage immigration for many people: names that seem ordinary in one place stand out in another. In her book The Name Jar, protagonist Unhei realizes, “Oh, I have a strange-sounding name.” Choi remembers her own arrival in the United States as an international student at 24: “English is the biggest monster I’ve ever encountered,” she says. “Even to this day, it makes me sweat, tremble, and freeze sometimes.” She recalls different-smelling places, different-tasting foods. So much is different for a young newcomer, she says, that it can be tempting to not want your name to be an additional difference.

That’s part of why Choi wrote The Name Jar, though her childhood informed it as well. In Korean, “ ‘Yang’ is gentle, and ‘sook’ is pure or clean in spirit,” she says. But in practice her name also sounds a bit like the word for bucket. “People would literally call out to me, ‘Hey, bucket, the ceiling is leaking.’” She knew they were just joking, but it still felt like a demotion from something special to a mere object.

In The Name Jar, protagonist Unhei has allies, including a classmate and her grandmother, who bolster her in choosing to be called by her own name all over again. That kind of plotline provides a unique opportunity to discuss “both helpful and hurtful responses to a name that is unfamiliar to most members of a school community,” says Judy Viertel, school librarian at Marshall Elementary School in San Francisco. “Teachers and librarians can use this book to promote deep conversations about respectful responses,” she says. For example, fourth grade readers can contemplate what adult characters in some of these books could have done to make sure less onus fell on the protagonist. And they can talk about why incidental diversity in literature is so important.

Chicago-based literacy specialist Nawal Qarooni relates to the characters’ experiences in many of these books.

“As an Iranian and Arab American who grew up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in a mostly white school with a unique name, I was made to feel my whole life like I was extremely different,” Qarooni says. Name books are important so “kids can see themselves,” she says, and even just “to show that not all names are Annie and Sara.”

She calls having books about names, and accompanying activities like asking kids to interview their caregivers about their own name stories, “essential and empowering.” A PTA or school library would do well to purchase name books as part of a larger equity initiative, she says, “regardless of teacher background or school population.”

Qarooni adds that she sees her son Ehsan’s opportunity to learn his name story as “a superpower.” With the right approach, she adds, “teachers can design their classrooms and communities in ways that support that power.”

Gail Cornwall is a San Francisco–based freelance writer.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!