The Fine Art of Genrefying Collections

Mystery? Sci-fi? Getting books in the right categories makes genrefying worth it and helps kids find what they want.

|

Courtesy of San Leandro Public Library |

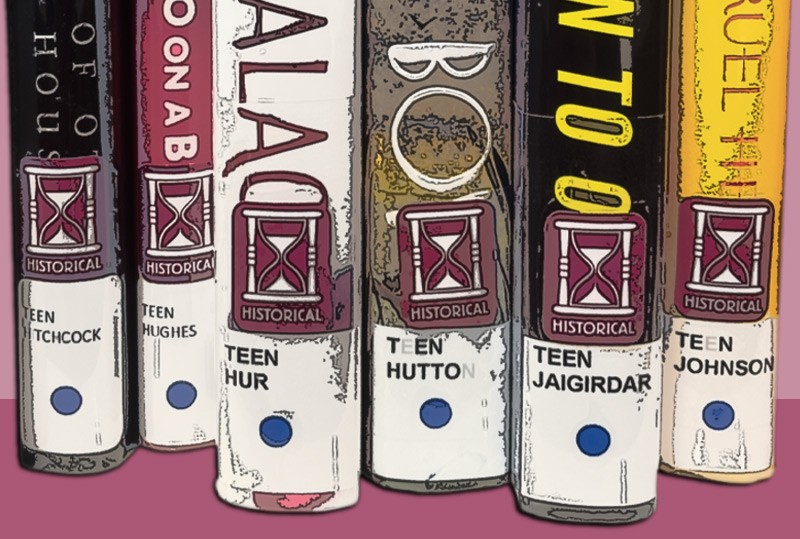

Imagine a middle grade novel told from the perspectives of both a Mars rover and a sixth grader. A tale written through letters and first-person narration, depicting interactions between humans and robots in a fact-based manner. What genre is this title? Would it go with realistic fiction, science fiction, or an entirely different category?

The book, A Rover’s Story by Jasmine Warga, has been labeled as all those categories and probably more. Warga, whose previous titles span the realms of young adult fiction (My Heart and Other Black Holes and Here We Are Now), verse (Other Words for Home), and realistic fiction (The Shape of Thunder), was initially surprised Rover was classified as sci-fi.

“I felt as close to Res as I have to any of my human narrators,” says Warga of the rover in her 2022 novel. “That said, I’m now convinced that science fiction probably is the best label. Though I like to think of the book as science fiction plus feelings or science fiction and letters.... But isn’t that how most genre classification goes?”

“I felt as close to Res as I have to any of my human narrators,” says Warga of the rover in her 2022 novel. “That said, I’m now convinced that science fiction probably is the best label. Though I like to think of the book as science fiction plus feelings or science fiction and letters.... But isn’t that how most genre classification goes?”

Warga isn’t the first author to be surprised by how her work has been categorized by librarians. The genrefying movement in libraries took a tip from bookstore organization with the goal of making it easier for patrons to browse by themes, not alphabetically by the author’s last name. But authors and librarians have differing views on genrefication. Can genres harm a hard-to-categorize book? What if titles are mis-genred?

“I can’t qualify [genres] as good or bad,” says young adult author and known genre blender Nic Stone. “Whether genres are restrictive or expansive depends on how we utilize them.” Stone’s middle grade novel Clean Getaway could be considered comedy and historical fiction, while her YA work Jackpot is more romance and adventure.

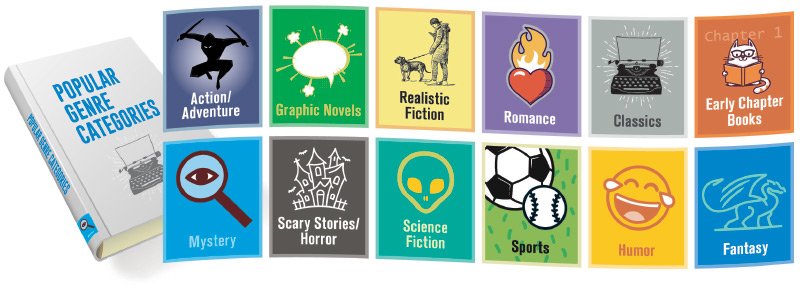

Historically, libraries are organized by format and age (picture books, chapter books, graphic novels) and then alphabetically by last name, with nonfiction organized by the Dewey decimal system. Bookstores more commonly sort by categories. To make the browsing experience more user-friendly, librarians have to a greater or lesser degree supplemented organization with finding aids, genre stickers, booklists, and separating out specific groups of books.

Mystery and graphic novels are most frequently grouped by genre; sci-fi and beginning chapter books are also popular breakout categories. Other sections may include humor, fantasy, scary stories, adventure, sports, classics, realistic fiction—basically, any possible topic. Full-on genrefying takes a lot of time and physical work hours, but can yield dramatic circulation results.

|

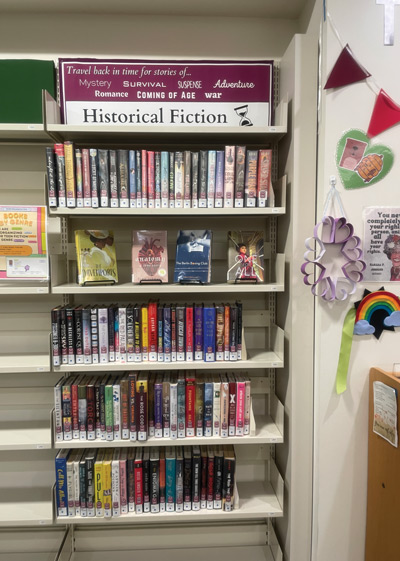

Browsable historical fiction at the San Leandro (CA) Public LibraryCourtesy of San Leandro Public Library |

The genre game

Some books are clear-cut horror or romance; some are more complicated. And others may span multiple genres.

Dragon Pearl by Yoon Ha Lee is a science fiction adventure with magic and folklore, while “The Incorrigible Children of Ashton Place” series by Maryrose Wood combines historical fiction, mystery, and even humor.

“Should we be pigeonholing these books?” asks Syntha Green, youth services librarian at the Baldwin (MI) Public Library, who recently de-genrefied her collection.

Gordon Korman, author of more than 100 books, is surprised at how many are classified as mysteries because they have a plot twist or late reveal. The entire series of “39 Clues,” to which he contributed, is often categorized as adventure, with random titles also pulled out as mystery.

“As a fan of the classic whodunit, that always catches me off guard,” says Korman, whose works are frequently associated with humor.

Middle grade author Stuart Gibbs writes series that can be labeled mystery (“FunJungle”), adventure (“Once Upon a Tim,” “Spy School”), or both (“Charlie Thorne”). His novel Moon Base Alpha also has a bit of science fiction, which means his books can be shelved all over the place.

Green recently interfiled mystery and science fiction books in her library, citing authors like Gibbs as a reason for doing so. Circulation was low in those genrefied sections compared to the rest of juvenile fiction. Individual books still have genre labels, though they’re mixed in together now. “Wildly popular authors like Stuart Gibbs are done a disservice by not having the ‘Space Case’ series with ‘Spy School’ and ‘FunJungle,’” she says.

Pros and cons

Julia Torres, a librarian in the Denver, CO, area, points out that genrefied libraries are much more accessible, particularly to people with language barriers who may have difficulty navigating an alphabetized collection.

“The problem with the current system is that it relies on a certain level of English proficiency,” Torres says. “It makes people more dependent on librarians than they need to be and creates unnecessary barriers to accessibility.”

Portia Carryer, a teen librarian at the San Leandro (CA) Public Library, recently genrefied her entire teen fiction collection. “There can be a tension in public libraries between findability and browsability,” says Carryer. Previously, books in her traditionally organized library had lots of genre labels, too. But “densely packed shelves whose titles are loaded with genre stickers felt overwhelming to patrons—and I could see it in my circulation statistics,” she says. “Genrefying the collection feels like a good balance.”

For authors, there’s an appeal to grouping books by last name, but they also understand the need for browsability.

“I would prefer that readers be able to find all of my books together,” says Gibbs. “Young readers often find an author they like and decide to read everything that author wrote. I certainly did that as a young reader. So, if all the books aren’t in the same place, then there’s a chance that the readers won’t realize how many books I have and therefore won’t read the others.”

“I refuse to speak against anything that might attract new readers to my books,” says Korman. “I know that War Stories and the ‘Titanic’ trilogy reached a lot of historical fiction buffs. The multi-author project ‘The 39 Clues’ brought my writing to a huge community of readers. I’m sure I picked up a lot of new fans along the way!”

Stone’s view? “I don’t really care how they organize the books,” she says. “My job is to be the writer.”

Genre blending

There’s no exact science to classifying, but narrowing down categories makes it easier, Carryer says. For example, if there isn’t a romance shelf location, a fantasy-romance would simply be shelved in fantasy.

Torres noted that if a library can purchase multiple copies of a book, they can easily be placed in multiple categories and moved around.

“A few times, I asked a student which genre they would consider the book to be in,” says Anne Clark, a media specialist at Leland (MI) Public School who recently genrefied her middle and high school libraries. “This was the case for the ‘Lord of the Rings’ series, which could have gone into adventure, classics, or fantasy. The student said, without pausing, ‘Definitely classics!’ so there it went.”

“My favorite thing is to blend two-genre conventions,” says Stone. “Your genre doesn’t need to fit one box. Instead, it can create a product we haven’t seen yet.”

Authors can be wary of genres because of the expectations that come with it, as Warga feels about a potential mystery she’s working on. There’s also the opinion that genre labels can overwhelm or deter potential readers. Or a library can be so genrefied that tiles get lost because a section is sandwiched between larger sections. Green remembered a humor section readers could never find because there was only one shelf.

Other genres, like romance or action, that may not be frequently requested by readers can be overlooked.

Ariel Birdoff, a school library media specialist at Mosaic Preparatory Academy in New York City, believes that genre labels can turn kids off to books they might otherwise read.

“I believe that labels do more prevention rather than encouragement,” Birdoff says. “When a book is labeled for theme or genre, it may tell potential readers ‘you won’t like this, don’t even bother.’”

Birdoff points to Kyle Lukoff’s Too Bright to See, a book with strong LGBTQIA+ themes that interested students might miss because it’s a ghost story that could be placed in the scary section.

“Similarly, if a book has queer themes and is labeled as such, a student might think ‘this book is for queer kids,’ without knowing it is accessible to everyone,” Birdoff says.

She notes another issue with prominent genre labels. “Another possible downside, especially if books are being labeled LGBTQIA+, is that it takes away the reader’s privacy when they are reading in public spaces.” And library labels such as “multicultural” or “OwnVoices” can be helpful for many browsers, but also not consider other key aspects of a particular book.

Ultimately, each library needs to find what works for them and their community. When Warga looks back at her childhood, she remembers admiring Lois Lowry and how different her books were, particularly The Giver and Number the Stars. Warga hopes readers can also find themselves liking new genres when reading her books.

All her books “center around the ideas of belonging, and that’s because I didn’t ever feel like I truly belonged anywhere when I was a kid,” she says. She returns to those themes again and again, “regardless of genre.”

“It can be hard to convince readers to follow you across various genres,” Warga notes. “I never want to disappoint readers, but I also feel creatively compelled to try my hand at telling many different types of stories. My hope is that there is a similar beating heart to all of my books that readers will recognize.”

Emily Mroczek-Bayci is a youth services librarian at the Arlington Heights (IL) Memorial Library and blogs for “Heavy Medal.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!