Stirring Up Trouble with 'The Crucible' | Challenging the Classics

The play about the Salem witch trials presents a moral dilemma, but it's another canonical work centering the white, Christian, male perspective. Here are suggestions for discussion and alternate works.

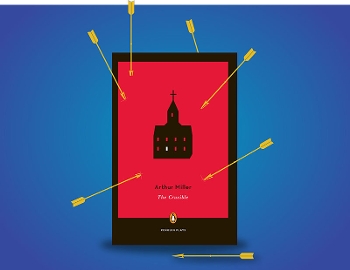

Arthur Miller’s 1953 play The Crucible has long been considered a part of the canon for American literature courses. Students are drawn in by the drama that accompanies hearsay, controversy, and public scandal. This makes sense, because if there is one thing all secondary teachers know, high school is full of all of these things.

Arthur Miller’s 1953 play The Crucible has long been considered a part of the canon for American literature courses. Students are drawn in by the drama that accompanies hearsay, controversy, and public scandal. This makes sense, because if there is one thing all secondary teachers know, high school is full of all of these things.

Miller’s play about the Salem witch trials of 1692-3 was conceived as an allegory for McCarthyism in the United States. Teachers often include the work on syllabi for courses because it parallels studies of American history, which is taught in 10th or 11th grade. The internet is full of lessons about the play’s central themes and its historical connections to McCarthyism, mass hysteria, religious persecution, scapegoating, and the ills of living in a patriarchal society.

In June 2018, the DisruptTexts community, through the guidance of its four co-founders (Tricia Ebarvia, Lorena Germán, Dr. Kim Parker, and Julia E. Torres) engaged in a Twitter chat about The Crucible. Through the chat summary, educators can read about the way the community is using the text as an entry point to discuss prison reform, white feminism, and how the work is one of too many pieces of canonical literature that disproportionately center the white, Christian, male perspective. More critical discourse comes through discussing Arthur Miller’s caricature of Blackness with the character Tituba, an enslaved woman accused of witchcraft, and the problematic way in which Indigenous people on whose land the play’s action takes place, are essentially absent from the narrative.

Though the play presents a moral dilemma, it’s one that belongs to some cultural groups, not all, and the almost exclusively all-white cast of characters is strictly divided into men who are inherently good, even when they “exercise bad judgment,” and women who are inherently evil.

By teaching The Crucible, educators can introduce students to the McCarthy era and examine propaganda, hearsay, and fake news. However, the question we come back to often in discussion about canonical works and their place in modern society is: What could be used instead?

READ: Weeding Out Racism’s Invisible Roots: Rethinking Children’s Classics | Opinion

Creating an education system that reflects and responds to students’ needs requires educators to de-center and disrupt systems of power and oppression that place their worldview over those of the oppressed and marginalized. Even if a course includes the critical components of examining the racism, sexism, erasure of Native people and centering of a white, male, Christian, patriarchal society, the play is still a work written by a dead, white, male author.

So, what are some alternates and companion reads? Ntozake Shange’s play For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow Is Enuf allows plenty of space for students to talk about women, specifically Black women, living, loving, and trying to survive in a society that is fundamentally racist and sexist. Reading The Thanksgiving Play and What Would Crazy Horse Do by Larissa FastHorse, students can think about the idea of “wokeness” and how good intentions planted in the soil of ignorance can often grow strange and bitter fruit. Benjamin Benne’s Alma (or #nowall) is a commentary on the trials and tribulations that often come between the “American Dream” and those who seek it, as well as the divide between documented and undocumented citizens, especially when these labels are held by people in the same family. Furthermore, Benne’s play In His Hands; or the gay christian play explores the intersections of religion and identity. Read more at the New Play Exchange, “the world’s largest digital library of scripts by living writers.”

In addition, Claudia Rankine’s new play Help looks at racial invisibility and white male privilege, and though it isn’t available yet for educators to read, the New York Times article, “I Wanted To Know What White Men Thought About Their Privilege, So I Asked,” is a fascinating introduction while we wait.

When educators are looking to evaluate the relevance of canonical works and their place in today’s classrooms, they can consider these questions:

- Whom does your curriculum center? What identities or voices are marginalized or erased altogether?

- What are the norms and values of your community? How can you problematize or push back against them in order to expand the worldview of students and young people within it?

- What new knowledge will teachers and students need to critically examine themselves and your chosen text?

- How will the text you’ve chosen amplify and center the work of living creators so that students can see themselves?

- What will you need to unlearn (what assumptions or understandings can you let go of) in order to make room for new knowledge?

Julia E. Torres is a cofounder of DisruptTexts and a librarian and ELA educator serving students and teachers in the Far Northeast region of Denver Public Schools.

READ: Little House, Big Problem: What To Do with “Classic” Books That Are Also Racist

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Emily Schneider

All of the works which you recommend to read alongside The Crucible are excellent choices. No work of literature stands alone; other perspectives enhance it. However, the suggestion to replace this brilliant work by one of our greatest authors because it is in some way limited is disturbing coming from educators and librarians. Which works of literature will survive your scrutiny, based on the identity of their authors? Are works by authors of color, women, and LGBTQ people exempt from your criteria? There are many ways to have fruitful, and critical, discussions of The Crucible. Rejecting it because “the play is still a work written by a dead, white, male author” is the antithesis of intellectual freedom and negates the right to read. What do you mean by asserting that the play’s moral dilemma belongs only to some cultural groups? Which cultural groups do you believe are immune to the type of mob reaction or mass hysteria which Miller depicts? Finally, since you have also emphasized the Christian component of the play, you might like to become more informed about how Miller’s Jewish identity impacted his work.

Posted : Sep 10, 2020 04:49