Spend It if You Can | SLJ 2024 Budget Survey

With budgets mostly flat, book challenges and rising costs pose hurdles for school librarians.

SLJ 2024 SCHOOL LIBRARY BUDGET AND SPENDING SURVEY

Most school libraries have a reliable source of funding these days, but librarians need to overcome an increasing number of obstacles to access it, according to the SLJ 2024 School Library Budget and Spending Survey.

Overall, school library budgets remained flat between 2022–23 and 2023–24, falling less than 1 percent. But as their dedicated library media center (LMC) budgets make up a smaller percentage of their overall funding, school libraries have come to rely more on federal and state money.

Meanwhile, stricter local or state regulations, especially in reaction to book challenges, mean that many librarians need additional approvals to use budgeted funds. Some aren’t allowed to buy books at all. More than half—58 percent—reported restrictions on spending, up from 48 percent in 2020–21.

Meanwhile, stricter local or state regulations, especially in reaction to book challenges, mean that many librarians need additional approvals to use budgeted funds. Some aren’t allowed to buy books at all. More than half—58 percent—reported restrictions on spending, up from 48 percent in 2020–21.

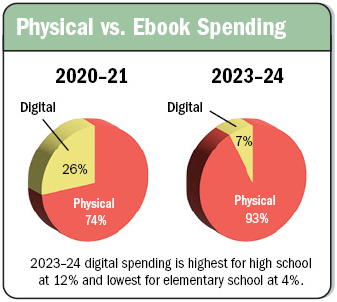

Librarians who can access budget funds primarily use them to buy print books and are spending much less on ebooks than at the height of the pandemic in 2020–21. They also use funds to upgrade library furniture. To supplement further, they rely on book fairs and other outside sources to help them keep their libraries stocked. Some dig into their own pockets.

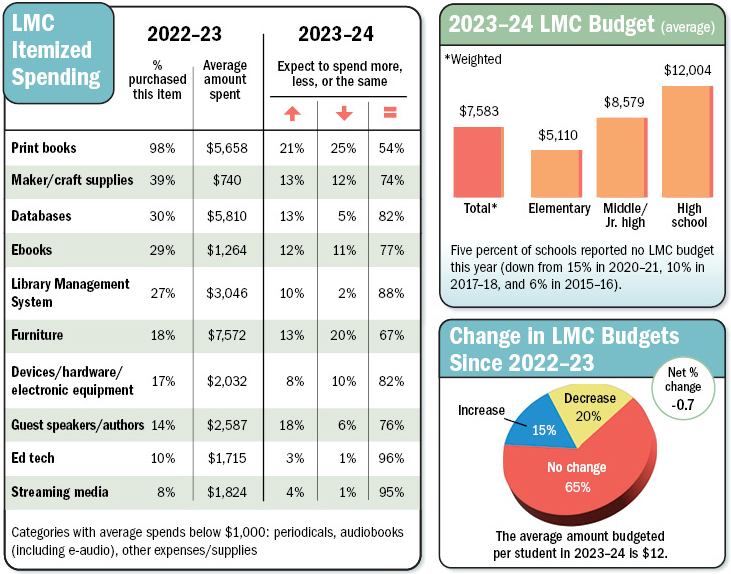

In good news, of the 708 U.S. school librarian respondents, only 5 percent reported having no LMC budget. This is a marked improvement from 15 percent in 2020–21. The average LMC budget for 2023–24 is $7,583, with an average of $12 budgeted per student.

And while 88 percent of responding schools have a full-time librarian or media specialist on staff—up from 84 percent in 2020–21—respondents also say they’re overstretched and can’t afford to hire help. “I am only at this school four days a week, rather than full-time, due to funding,” said Erin Sawaski, library media specialist at Parkview Middle School (WI).

Rules on spending

In terms of line-item spending, many say they can only use their budgets for books and library supplies, or they can only order through approved vendors. “I am given several ‘fund codes,’ and only money in those accounts may be spent on those items,” wrote Amber Walley, lead school library media specialist in the Wayne County (MS) School District.

“Any furniture, makerspace kits, display equipment, or other non-text items need to be specially cleared, or purchased solely by the PTA,” added an elementary librarian in Oregon.

Recent book challenges have impacted 11 percent of respondents. “Our book purchases are on hold altogether until at least January due to the district’s challenges and revision to policy,” said Becky Ortega, librarian in the Plano (TX) ISD.

Another high school librarian in Texas stated, “We are not purchasing books.”

Another high school librarian in Texas stated, “We are not purchasing books.”

From Indiana, a middle school librarian wrote, “Books with any LGBTQ+ characters are not encouraged at this time.”

“It has thus far not affected my budget, but Moms for Liberty has challenged over 60 titles in our county since spring of 2023,” wrote Karen Dulany, media specialist at Carroll County (MD) Public Schools. “Going forward, we will have to fill out and sign a form for each book we purchase, which may affect our purchasing decisions.”

In 2022–23, 98 percent of school libraries bought print books, spending an average of $5,658. Print makes up 93 percent of book spending, up from 74 percent in 2020–21. Only 7 percent of spending went to ebooks, down from 26 percent in 2020–21.

Money spent on furniture has increased, too. Eighteen percent of respondents spent an average of $7,572 in 2023–24, up from $2,534 in 2020–21. Several used federal Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funds for this. The next highest level of spending was on databases, by 30 percent of respondents, at $5,810.

Still, librarians who have reliable budgets reported that funding is falling short. Twenty percent of respondents dealt with budget cuts, while 15 percent got an increase.

Download and read the full Spending Survey report

“Districtwide, many of our librarians are commenting on how their budgets were cut this year,” said a Texas middle school librarian. “We are the fastest-growing district in Texas, and we are already pretty large, so this is worrisome.”

“I had the original budget of $7,500 restored after three years of effort,” wrote a middle/high school librarian in New York. “This budget was slashed to nothing due to my predecessor failing to order any materials.”

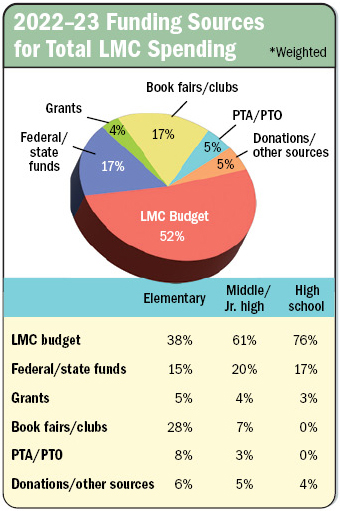

LMC budgets account for 52 percent of school libraries’ total funding, down slightly from 54 percent in 2020–21. Librarians also depend on federal and state funds (17 percent), book fair or club money (17 percent), PTA/PTO funding (5 percent), and grants (4 percent).

They find other ways to fund what they need, including birthday book programs, candy sales, read-a-thons, coin drives, concession sales, cafes, craft fairs, or selling used books. “I’ve never had a budget—I’ve always pulled books from book fairs, purchased with my own money, or received Title 1 money,” noted Lisa Dyson, library coordinator at Dolores Huerta Middle School (CA).

Bonnie McBride, librarian at Fenway High School (MA), said, “Our school has a foundation that does fundraising for us. They have given us $10,000 a year for the past 20 years.”

Bonnie McBride, librarian at Fenway High School (MA), said, “Our school has a foundation that does fundraising for us. They have given us $10,000 a year for the past 20 years.”

“I rely on a community member who purchases off an Amazon wish list of books,” said Jenny Gapp, teacher librarian at Peninsula Elementary (OR). “I rely on a PTA grant to purchase award-winning books.”

Also read: SLJ’s 2023 Average Book Prices

“Families can donate $20 for a new book to be donated to the library in honor of their child’s birthday,” an elementary librarian in Texas wrote.

However, multiple respondents don’t have the time or resources to hunt down outside funding. “Book fairs drain the life from me,” wrote a California elementary librarian. “I try to do grant writing on the side, but can’t get it done every year.”

Others can’t expect local families to contribute. A middle school librarian in Minnesota wrote, “Students and families can’t afford to buy books [at our] Title 1 school. The only avenues are to look for grants, DonorsChoose, etc.”

And some respondents don’t even have outside options. “I am not permitted to fundraise. My principal said it is a bad look,” wrote an Ohio high school librarian.

Obstacles, priorities, and partnerships

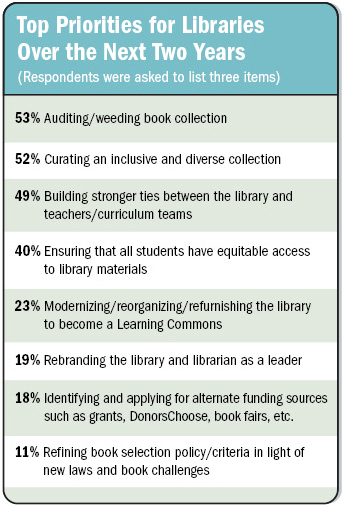

To account for inconsistent funding, respondents have reorganized their spending. While the percentage of spending on fiction is still 64 percent, the same as in 2021, librarians are budgeting less for periodicals and more for graphic novels, manga, and ESL titles. Others are trying to spend less on other things in order to buy more books.

Laura Ehling, elementary media specialist at Rochester (MN) Public Schools noted, “More money spent on databases and author visits for the district. Less on popular books.”

Laura Ehling, elementary media specialist at Rochester (MN) Public Schools noted, “More money spent on databases and author visits for the district. Less on popular books.”

An elementary librarian in Illinois said the real issue in budgeting is that “items are more expensive, so my money doesn’t go as far. Also, students are not as careful with books as they were a few years ago, so I spend more with replacement.”

Currently, 60 percent of respondents say there is a specific need they’ve been unable to fill, up from 54 percent. Many couldn’t update or replace their collections, even as books went missing during the pandemic. They’ve also been unable to upgrade furniture and shelving, access ebooks or databases, schedule author visits, or buy makerspace or STEM materials.

An elementary librarian in Georgia said their collection is out of date, but if they weeded fully they wouldn’t be able to buy enough replacement books. “As is, due to water damage, we have entire sections of empty shelves.”

And librarians are spending more of their own money than before. Seventy-nine percent of respondents spent $384, on average, on their libraries last year, up from the average $333 spent by 75 percent of librarians in 2020–21. Currently, a majority of librarians open their wallets to buy books on Amazon, discount sites like Bargain Books and First Book Marketplace, or in thrift stores, especially when titles aren’t available through approved vendors.

“I would love to not have to spend my own money on books for our library,” said an elementary librarian in New York. “We are lucky if we even get $5 back toward replacing a $25 book. It is really sad when I see brand-new books disappear within the first few weeks of being in circulation, but I cannot (and will not) keep books out of the students’ hands.”

Respondents also bought book bins, bookmarks, craft supplies, puzzles, games, candy, prizes, decorations, cleaning supplies, software, makerspace items, food, drinks, furniture, and lesson plans. Some said they needed items too quickly to wait for the requisition process.

Many school librarians gain support by sharing resources with their local public library. On a scale of 0 to 10, measuring the degree to which they partner, librarians rated an average of 4.3, consistent with 2021. Students can use their student IDs to access public library resources, and school libraries share Sora or database access with public libraries. Respondents are also able to coordinate author visits, Battle of the Books programs, public library “field trips,” bookmobiles, ebook access, and summer reading programs with public libraries. “Our public library is amazing and supportive,” said Kara Foutz, information literacy specialist at West Middle School (MI).

Some respondents haven’t been able to create such arrangements yet, while for others the process has become harder. “We have done this in previous years. Due to the book challengers this will be difficult this year,” said a Maryland high school librarian.

For others, determined planning and persistence pays off. “I feel fortunate to have great financial support from my district and school, but I also research, plan, and advocate heavily for those funds,” said Sherry V. Neal, school librarian/media specialist at David T. Howard Middle School (GA). “We are a charter district, and schools have flexibility in how state- and district-allocated funds are actually used on the ground. I think librarians need intensive training on asking for the funds that students deserve to have access to a robust, equitable library program.”

|

METHODOLOGY A survey invitation was emailed to a random sample of school librarians on October 16, 2023. The survey was also advertised in SLJ’s “Extra Helping” newsletter. The survey closed on October 30, 2023, with 708 U.S. responses. The data is weighted by type of library. Tabulation and analysis were performed by SLJ research. Download the full report here. |

Marlaina Cockcroft is a writer and editor with a passion for children’s books.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!