COVID’s Long Shadow Centers Social-Emotional Learning in Schools

The strains of the pandemic have shown how critical SEL is to school communities, particularly those serving at-risk children.

|

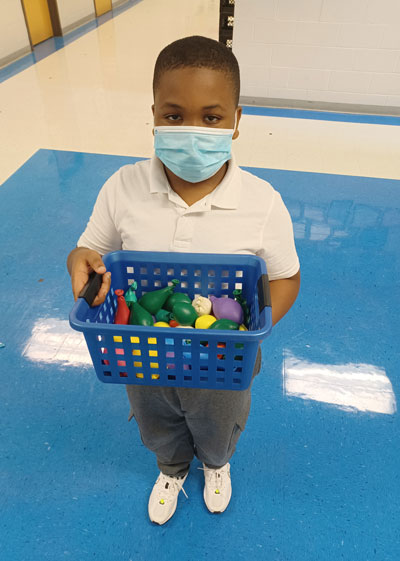

Fall-Hamilton Elementary School students use breathing and movement to instill calm and self-regulation skills to prepare for learning.Photos courtesy of Fall-Hamilton Elementary School |

|

Relatd Article: |

Students have transitioned between in-person school, hybrid school, and virtual school with little warning. They have endured the stress and isolation of lockdown. Their families have lost income, lost jobs, and dealt with mental health pressure. And many have gotten sick and lost loved ones to COVID-19.

These student stressors have been top of mind for Dau Jok, the social and emotional learning (SEL) coordinator for Des Moines (IA) Public Schools (DMPS). So, heading into the 2021–22 school year, nearly 18 months into the pandemic, he decided to help kids by focusing his work where he knew it would make the greatest impact: on adults.

“The natural tendency when we’re doing SEL is to go straight to the kids, because we want to fix them,” says Jok, who’s a member of the inaugural cohort of the SEL Fellows Academy organized by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL). He started as the SEL coordinator in Des Moines in October of 2020, after the school board made SEL a district priority the year before. “But a dysregulated adult cannot help a dysregulated child.”

All the pressures that students face have also been borne by teachers, librarians, and school administrators over the past year and a half of the pandemic. What’s more, teachers and staff have had to learn new practices at warp speed, while being constantly dogged by dire warnings that students are losing ground academically.

Essentially, educators get the message that they’re failing at a time when their performance expectations are sky-high and they need to advocate for their own workplace health and safety during a rapidly changing public health crisis.

“Despite the pandemic, we always look at the test scores.…We try to quantify human experience in an extremely difficult time,” Jok says. “That misses the mark. It doesn’t tell the story of all the different challenges; all the stories of hope, success, overcoming, resilience, and innovation.”

It’s become common practice in recent years for school districts to adopt SEL standards that make building skills in relationships, self-regulation, and emotional intelligence part of a student’s education. All 50 states have adopted these standards for preschool, with 15 extending the standards to higher grades. The strains of the pandemic have shown how critical SEL is to school communities, particularly those serving at-risk children.

Research has shown that SEL programs improve attendance, behavior, grades, and graduation rates for the hundreds of thousands of students who have been exposed to them. A school’s SEL program may include the adoption of a SEL curriculum that uses direct instruction to teach how to be an upstander against bullying and how to help yourself calm down when you’re upset. And recognizing that racism, sexism, homophobia, and other prejudices have a large impact on students’ social and emotional wellness, SEL practices can be a tool to increase equity within a school by affirming students’ backgrounds and identities, fostering self-awareness, and building respectful cross-cultural relationships.

The best programs, according to experts, focus on spreading SEL practices by infusing them throughout the school’s culture.

“Every kid needs to be heard and have a safe, nurturing relationship with an adult inside the school,” says Mathew Portell, principal of Fall-Hamilton Elementary School in Nashville, TN, and a national speaker about SEL.

Portell says that wide geographic, socioeconomic, and racial differences in school districts across the country mean the pandemic affected different communities in different ways.

“The pandemic exposed the equity gap in our country,” he says. He also believes that the pandemic reinforced the importance of the school’s role in a student’s social and emotional health. School leaders who tune in to the challenges and strengths of their own communities will have the most success in using SEL tools to build nurturing school cultures for their students and staff.

“[SEL] curriculum builds common language; it’s a plate that everything sits upon. But the table is the school culture,” he says.

Community care; understanding behaviors

Transforming school culture starts at the top. That’s why some school leaders say it’s essential to direct SEL resources toward helping educators heal from the stresses of working during COVID.

In Des Moines, this will take the form of a three-hour workshop at each school site, and it’s not your average professional development seminar. More than anything, Jok says, he wants to show gratitude to teachers and staff for their contributions by making space for them to connect, heal, and build relationships with one another—to be human.

“It’s difficult to remember that you’re appreciated if you’re having to take care of yourself on your own time,” Jok says. Educators are often told to practice “self-care” in order to maintain their physical and mental health. But that advice can be trite and invalidating, according to Jok. A better practice is for institutions to set aside time for adult SEL during the workday. In the DMPS workshops, teachers and staff are invited to explore the things they value about themselves, share challenges with their colleagues, and learn how to better understand other people’s emotions. It’s what Jok calls “community care,” and he says this investment in staff empathy will unquestionably benefit students.

|

Students at Fall-Hamilton Elementary made stress balls from rice and balloons for staff. |

“Emotions are contagious,” he says.

In Smyth County, VA, residents knew the challenges the community faced well before the arrival of COVID-19. More than half of the students in this largely white, rural district are considered economically disadvantaged by the Virginia Department of Education. In 2018, the county hospital found that the number of local babies born addicted to substances was many times the state average. In addition, meth and opioid abuse had exploded incarceration rates, driving the region’s annual jail costs from $675,000 in 2010 to $2.9 million by 2019.

“If we’re spending the money on incarceration and not public education, we have an issue,” says Dennis Carter, superintendent of Smyth County Public Schools.

The data served as a wake-up call for the entire county, and in 2018 more than 200 county educators, social service providers, law enforcement officers, health care workers, and parents came together for a training about childhood trauma. They learned that adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), such as child abuse, exposure to substance abuse, or incarceration of an immediate family member, are predictors of lifelong health problems such as heart disease, depression, and drug abuse.

With the help of Becky Haas, an expert on ACEs who was then the regional health system’s trauma-informed administrator, the school district adopted trauma-sensitive practices that focused on building resilience in students and families to act as a buffer against trauma.

“Early childhood trauma really affects the brain and the way the brain functions. You might have a 10-year-old in front of you, but if they’ve experienced a lot of childhood trauma, their brain may be still functioning at a five-year-old level,” says Rebecca Tolley, a librarian at East Tennessee State University and author of A Trauma-Informed Approach to Library Services (ALA, 2020).

Tolley explains that cortisol, the hormone that spikes when a person is in distress, can remain constantly elevated for children who have experienced trauma. “They’re always up or on, expecting something, hypervigilant, primed to be reactive. If all their energy is going to that, that doesn’t leave a lot of bandwidth to develop social and emotional [skills],” she says.

That’s where SEL comes in: schools and libraries can provide environments that are intentionally crafted to help students develop their self-regulation, emotional intelligence, and relationship skills when they might need extra help building those capabilities. In a school library, that can mean designing calm-down spaces with puzzles or quiet activities, creating predictable routines, providing books that affirm students’ identities, and engaging in respectful communication in which students are given choices rather than commands.

In Smyth County, the sheriff’s office developed a program called Law Enforcement Notifying Schools (LENS), in which law enforcement would notify a child’s school if an officer visited a student’s home for any reason. The details were kept confidential, but teachers and staff were able to give a student extra attention at a moment when they might be experiencing heightened stress. The focus is on understanding the root causes of students’ challenges and using the resources available to strengthen families.

Trauma-informed educators consider student behavior a type of communication: If a student is acting out, it’s because they don’t have the capacity to behave in a more socially acceptable way. The solution is building trusting relationships and bolstering their social and emotional skills, not enforcing hierarchical and punitive disciplinary measures. Reforming school discipline practices is also a matter of equity: students of color are suspended at disproportionate rates, and they are often perceived as more threatening than white students engaging in the same behavior.

“We wrap our arms around our students”

Some practices that developed during COVID will continue in the coming years, educators say. In many communities, the challenges of COVID have forced schools, nonprofits, after-school programs, and families to pull together as never before and collaborate in new ways. The rapid adoption of new digital tools has made communication easier across schools and school districts. In the Sacramento City (CA) Unified School District, SEL director Mai Xi Lee sent teachers weekly slide presentations teaching SEL skills that they could play for their students over Zoom during remote learning. Her office also provided teachers with tips for social and emotional care for adults, and suggested classroom activities such as read-alouds for Asian Pacific American Heritage Month and Black History Month to affirm the identities of students in Sacramento’s school district, where more than 75 percent of students were BIPOC as of the 2016–17 school year.

“The gist of the return this year is about how do we wrap our arms around our students to make sure they feel a sense of community, that we are affirming their sense of identity however they show up, that we are nurturing their sense of belonging, and that we are cultivating their sense of agency,” Lee says.

As essential workers on the front lines, educators are often starkly aware that the impacts of the pandemic were felt unevenly through society. In the U.S., Black and Latinx people were 2.8 times as likely to be hospitalized for COVID and twice as likely to die of it, according to the CDC. Blue-collar workers who could not telecommute had higher exposure to the virus. Low-income communities felt sharper financial impacts from the lockdown and subsequent economic uncertainty. The pandemic shone a bright light on society’s inequalities.

“There’s no going back to normal,” says Jok, whose district is made up of more than 60 percent students of color with 76 percent of students on free or reduced-price lunch. As a diverse, urban school district in a largely white, rural state, DMPS has also felt the effects of a political climate in which the demonization of critical race theory has led more than 20 state legislatures to introduce legislation that would effectively ban teaching about race or racism. In June, Iowa governor Kim Reynolds signed House File 802, a law that bans teaching that the United States or Iowa is systemically racist or that any individual is inherently biased based on their background.

“For SEL, that becomes consequential,” Jok says. “Race is a socially constructed concept; however, it has shaped our history. The same thing with class, sex, and gender. We need to have identities affirmed in our buildings.”

At their most optimistic, educators say that they hope that the pandemic has exposed racial and economic inequities in a way that will make them impossible to ignore in the future.

“We know we can’t return to normal, because normal wasn’t working for many of our students,” Lee says.

Because Smyth County schools had started doing significant SEL work before COVID, in many ways they were able to hit the ground running when lockdown started. The school system immediately set up a food delivery system with teachers, librarians, and staff bring food directly to students’ homes. Staff made well visits and calls to students, and the school district set up a crisis hotline for students, parents, and staff for mental health issues. In February, more than 100 school district staff volunteered for a trauma task force. Haas spoke at the first meeting and urged the group to focus on their own mental and emotional health.

As the school year progresses, Carter is most concerned about access to mental health care: the need for it has increased, and access to it is lacking nationally, he says. Smyth County Public schools have partnered with the regional health system to place tele-mental health and tele-med services in almost every school in the district, so that students who need mental health support can get it immediately on-site and avoid emergency rooms. He draws inspiration from a student-initiated program at one of his district’s high schools called “Suds for our Buds” that provides free laundry services, a clothes closet, and hygiene products for students who can use them, no questions asked.

“Kids and staff are amazing,” Carter says. “They are resilient and have pivoted with us time and time again as the navigation of COVID-19 has led us through the past many months.”

Drew Himmelstein covers education, families, and religion.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!