A Black History Trove: Teaching with the #SchomburgSyllabus and Its Primary Sources

The online resource from NYPL's Schomburg Center archives Black history, culture, movements, and experiences.

|

|

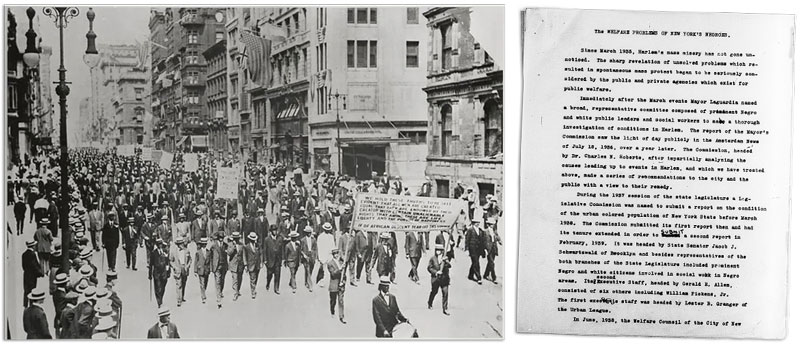

From the left: 1917 Silent Protest parade in New York City in response to the East St. Louis race riot; “The Welfare Problems of New York’s Negroes” by Harry Robinson, Writers’ Program, NYC, 1939.

|

When I was growing up in the 1990s and early 2000s in South Carolina, Black history was mostly squeezed into the shortest month of the year and in surface-level discussions of slavery and the civil rights movement. Latinx culture received its spotlight in jovial, uncontextualized celebrations of Cinco de Mayo. Native American culture was celebrated by giving students “Indian names” and dressing us up in fringed T-shirts and feathered headbands. Teachers discussed Asian and Pacific Islander cultures only in connection with World War II.

In short, our teachers rarely implemented a culturally responsive pedagogical approach beyond superficial attempts to be more diverse.

Exploring Primary Sources in the ClassroomThe 27 themes in the online syllabus range from Afrofuturism & Comics, Environmental Racism, and Fashion, to Policing, Mass Incarceration & Abolition, and Writers & Literature. They are visualized with thematically related images from NYPL’s digital collections. There are many ways middle and high school teachers can explore the content with their students. Once viewers select a theme, they are directed to a short list of resources that could introduce new areas of study or enrich current ones. For example, a student interested in Afrofuturism could be introduced to the writings of Sun-Ra or the digital exhibition Nonlinear Pendulums: Voyage Through Infinite Blackness, curated by the 2019–20 Schomburg Center Teen Curators. The themes can also be used in a classroom to identify reading material for a focused syllabus and primary sources providing insight into larger curricular units.

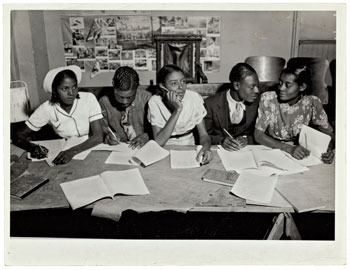

Students writing, c. 1935-1943.

|

Students weren’t taught to consider the historical context of real-life experiences outside the classroom, either. There was no curriculum on why, every Martin Luther King Jr. holiday, African American South Carolinians marched to the South Carolina Statehouse with demands to remove the Confederate flag. No resources on the Islamophobia experienced throughout the world and in schools after 9/11. Students like me were often shushed for mentioning Black historical figures not included in the curriculum, like Malcolm X, Ella Baker, and Assata Shakur. I educated myself in my parents’ home libraries.

The hashtag syllabus movement

In recent years, hashtag syllabi, prompted by social justice protests, have provided resources on Black history and contextualized current events on a global scale. My involvement with the #SchomburgSyllabus, including primary sources in Black history and an educational tool for middle and high school teachers, extends this work.

Georgetown history professor Marcia Chatelain started the #FergusonSyllabus following the killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown by police on August 9, 2014, in Ferguson, MO. Chatelain was building on a legacy of self-directed education efforts in African American communities. “When schools opened across the country, how were they going to talk about what happened? My idea was simple, but has resonated across the country,” Chatelain wrote. “Reach out to the educators who use Twitter. Ask them to commit to talking about Ferguson on the first day of classes. Suggest a book, an article, a film, a song, a piece of artwork, or an assignment that speaks to some aspect of Ferguson. Use the hashtag: #Ferguson-Syllabus.”

The #FergusonSyllabus enabled students and educators to learn about, contextualize, interrogate, and critique the world around them. Hashtag syllabi are “artifacts of culturally responsive teaching,” writes media studies scholar Meredith D. Clark. “The individuals who created and contributed to the syllabi recognized that their colleagues would need non-normative literature to guide students through critical examinations of acute episodes of white violence.”

Since the #FergusonSyllabus, we’ve seen many other hashtag syllabi: the #CharlestonSyllabus, #PRSyllabus, #coronavirus-syllabus, #BlackIslamSyllabus, #PopoloSyllabus, and more. All encourage culturally relevant teaching in the classroom and self-directed learning outside of it.

Recognizing that content in crowdsourced hashtag syllabi could be lost to the ephemerality of the Web, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, part of the New York Public Library (NYPL), began web archiving hashtag syllabi in 2017 under Makiba Foster, then assistant chief librarian in the Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference Division. Participating in Archive-It and the Internet Archive’s Community Webs program, the Schomburg Center joined 26 other public libraries to develop expertise in web archiving and build web-based community history collections.

The result was the #HashtagSyllabusMovement collection, now called the #Syllabus collection, with educational material “related to publicly produced and crowd-sourced content highlighting race, police violence, and other social justice issues within the Black community,” according to Foster. The #Syllabus collection archives Black-authored and Black-related resources to document Black studies, movements, and experiences in the 21st century.

|

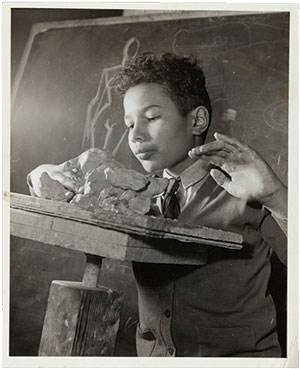

Child sculpting at the Harlem Arts Center, 1939. |

#SchomburgSyllabus project

As the digital archivist at the Schomburg Center for two years, I collected and archived online materials for the #SchomburgSyllabus that can be used for classroom curriculum, collective study, self-directed education, and social media and internet research. The syllabus includes Schomburg Center primary sources in its 27 themes, which serve as guides to topics in Black diasporic history and an introduction to the Schomburg’s 11 million items.

Launched in September 2021, the syllabus marked the 95th anniversary of NYPL’s acquisition of Afro-Puerto Rican scholar, historian, writer, activist collector, and curator Arturo Schomburg’s collection in 1926. The collaborative efforts that enabled Schomburg to amass his collection mirror those driving hashtag syllabi and the #SchomburgSyllabus today. This project is a celebration of the legacy of Black self-education and Black librarianship, and the resources are drawn from the Schomburg’s five divisions: Jean Blackwell Hutson Research and Reference; Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books; Photographs and Prints; Art and Artifacts; and Moving Image and Recorded Sound; and staff blog posts, LibGuides, exhibitions, public programs, and the Black Liberation Reading List.

In honor of the 135th Street Library Branch, where the Schomburg Center began, I curated 135 items that represent just a slice of the resources available on the 27 topics. The syllabus is intended to be a guide in self-directed learning as we try to “understand both the past and its representation in the present,” in the words of historian Jennifer L. Morgan.

“Real education means to inspire people to live more abundantly, to learn to begin with life as they find it and make it better,” Carter G. Woodson wrote in The Mis-Education of the Negro, which sat in my dad’s library. Like the materials I found on those bookshelves, the #SchomburgSyllabus can inspire people to understand the history that preceded them, contextualize the world around them, and build a better world for themselves and others.

|

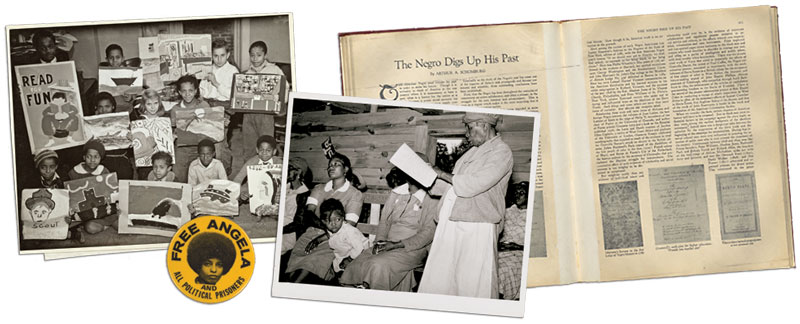

From left: “Free Angela” button; Flatbush art students showing examples of their work, 1935; star pupil, 82 years old, in adult class, Alabama, 1939; article by Arturo Schomburg in Harlem: Mecca of the New Negro, 1925. |

Zakiya Collier is a Brooklyn-based, Black, queer archivist and memory worker.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!