YA Grows Up: Teen Protagonists Step into Adulthood

YA books with older characters appeal to teens looking ahead in life and adults drawn to themes of self-discovery and affirmation.

Courtney Summers’s novel The Project follows a 19-year-old who works for a magazine as she investigates a mysterious cult. In an interview with SLJ, Summers maintained that, though it doesn’t take place in school or feature a high school–age protagonist, it truly is a YA novel.

The book deserves its YA stamp because it embraces “how varied, diverse, and ‘grown up’ the teen experience actually is,” Summers said.

YA books, particularly those with older characters like The Project, can exist in a liminal space that appeals to many different ages of reader: Teens wanting to grow up, and adults who may never truly feel grown.

Indeed, books that reflect the teen experience are as varied as teens themselves. “[YA is] a relatively recent phenomenon in terms of being

a dedicated genre that has its own style or distinct voice,” says Lalitha Nataraj, social sciences librarian at California State University San Marcos. “It gets this bad rap because people don’t understand teenagers all the time.”

“People don’t realize that this is really profound literature,” Nataraj continues. “A lot of [these books] serve as primers for self-development, self-actualization, learning to do the right thing, making certain choices in our lives, leaving childhood behind, and stepping into adulthood.”

Stepping into adulthood is something more YA characters are doing. Many of these books center on characters 18 and older—out of high school, in college, or working full time. (These settings are found most in realistic fiction; sci-fi, fantasy, and historical fiction plots aren’t as often tied to traditional markers of teen life.)

READ: YA Goes Adulting: 14 Crossover Titles with Older Teen Characters

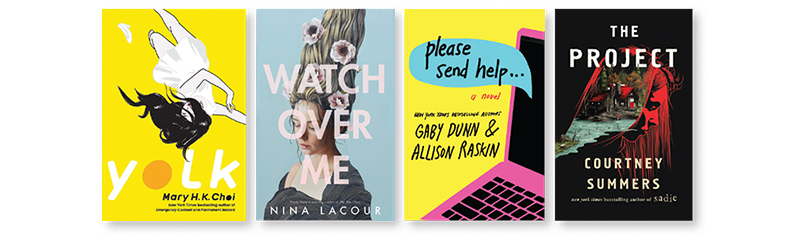

Mary H.K. Choi’s Yolk, for instance, is told from the perspective of a 20-year-old design student in Manhattan. Nina LaCour’s Watch Over Me is about a young woman who works as a teacher at a farm after aging out of foster care. In Allison Raskin and Gaby Dunn’s Please Send Help, best friends navigate post-college jobs and relationships. These types of novels are often referred to as “crossover” YA—books most likely to appeal to adult readers. They sometimes feature elevated language or steamy scenes, like Sarah J. Maas’s sexy high-fantasy “A Court of Thorns and Roses” series, which began as YA and is now published as adult. Books like this may also be classified as New Adult, a term that sometimes indicates the presence of sexual content, hewing closer to traditional romance titles, though it’s not a common section in bookstores or libraries.

How are they published?

Publishers have varied relationships with these types of books. Some are actively seeking them.

Wednesday Books, an imprint of St. Martin’s Press, specializes in exactly this type of older teen fare. Because the imprint was created within an adult house rather than a children’s publisher, it is primed to reach an adult market, and the books cross age lines.

“Often, the best indicator of true crossover readership is what our ebook numbers look like, because for the most part, the teen audience still seems to be buying physical,” says editorial director Sara Goodman. “When our titles have large ebook numbers, we’re probably getting a lot of adult readers.”

Julie Strauss-Gabel, president and publisher of Dutton Books for Young Readers, which publishes Nina LaCour’s titles, looks for books that challenge what YA can be.

“I am absolutely always looking for books that reach beyond—even defy—the traditional boundaries of young adult,” she says.

The romance publisher Entangled publishes New Adult and crossover YA books, including some titles suggested for readers age 16 and up. For publisher Liz Pelletier, putting out older teen books is a way of keeping readers who may have moved on to adult novels.

“Offering them this sort of crossover or New Adult title is a way to retain their interest while giving them themes and characters they can relate to—moving out of the house, being on their own for the first time, separating from their parents or childhood friends, general independence,” she says. “They’re important coming-of-age issues for older teens.”

Some publishers don’t differentiate between crossover books and other YA titles.

“I publish young adult, and if adults come to [the books] that’s great,” says Melanie Nolan, publishing director at Alfred A. Knopf Books for Young Readers. “The smart ones usually do.”

Liz Bicknell, Candlewick executive editorial director, doesn’t think about age—of characters or readers—when acquiring.

READ: Middle Grade Is too Young, YA too Old. Where Are the Just-Right Books for Tweens?

“It wouldn’t matter to me if the main character were 16 or 19,” she said. “I think it’s really more about the emotions of the story and what is happening in both the character’s psyche and the reader’s psyche. And if they match up, then that’ll be fabulous.”

What’s the distinction?

Still, it can be hard even for the experts to define what makes a novel YA or adult. In some cases, it’s as subjective as a certain tone or feeling.

“With writing we’ve seen lately, like with Nina LaCour’s books and some of the texts that get a lot of attention with the Printz, it’s hard to separate what is strictly for a YA audience versus New Adult, or adult,” says Nataraj. “That just goes to show that young adult literature itself is very complex.”

Young adult fiction tends to be focused on a teen’s voice and centered on their experience, sometimes written in present tense and first person.

“It comes down to the protagonist, and whether their journey is fully rooted in a young person’s space in the world, or is posed with the benefit of hindsight,” Nolan says. “There’s a point of discovery or an awareness of situations or conflicts that YA authors manage to draw out with a skill and a truthfulness that I can’t say I always see in an adult book.”

Sometimes, the distinction is based on marketing and sales. Bicknell says that when she first edited a book starring an 18-year-old, Barnes and Noble did not consider it young adult. “That was a bit shocking, because in real life you have mature readers who are 12 and 14, and less mature ones who are 18 and 20,” she says.

Who are crossover books for?

Many adult readers may still relate to the common YA themes of discovering their identity.

“I can’t get enough of it,” Goodman says. “I’ll return to it over and over. A coming-of-age story—I’m constantly going to be processing that part of my life.”

For adults, these stories can be both comfort and affirmation. The books grown-up readers needed in their youth are still a way of reflecting their younger selves. Newer stories featuring diverse characters may bring in adult readers who wish those books existed when they were growing up.

“Not a lot of us have gotten to see characters who are written with particular voices or cultural backgrounds,” Nataraj said. “When you see that someone else is writing about your childhood experience, that brings it into stark relief like, ‘Oh, yeah, that that is kind of how it was.’ There’s a sense of validation, right? And I think that young adult fiction can do that.”

“I think it can be a healing experience for many people, when they see themselves or when they see their stories,” Nataraj adds. “You don’t feel invisible.”

“There’s been a real call by librarians to address issues and represent voices that haven’t been traditionally represented,” Goodman adds.

With the popularity of YA books among adults, it’s natural to wonder whether upper YA books really serve teens. But teens are checking them out, librarians say.

“None of the [students] seem to want to read any books that have a character who is younger than them,” says Karin Greenberg, library media specialist at Manhasset (NY) High School. “In high school, they really do have an interest in books that have college-age characters or even older, even in their twenties, thirties, as opposed to books that have [characters] on the younger end.”

At Griffin Middle School in Frisco, TX, eighth graders also gravitate toward older YA titles, according to librarian Ashley Leffel. “Middle school is pretty much a coming-of-age place. Your hormones are hitting, everything is new and different, and you’re awkward,” she says. “When you get characters who are transitioning that summer between high school and college, it’s the same thing you’re headed towards. Adulthood. You’re feeling that kind of awkward newness, and I think they enjoy that.”

Teenagers also appreciate the aspirational quality of older YA books. “The teens are always so self-aware and self-conscious about anything they do because they don’t want to be seen as teens [or] naive or inexperienced,” Greenberg says. “They’re curious to see what the next stages of their lives might be like. That’s exciting to read about.”

Why are they so appealing?

Even if young readers are interested, there are challenges to having these books available for teens. Leffel says that many of these books skew too old for her to shelve in her middle school, but she can refer her eighth graders to the public library with their parents’ supervision.

Some of the difficulty is in the terminology. If “young adult” actually means “teen,” should books about the late teens and early twenties—true young adults—be shelved with adult books?

“Having such a large adult category is really hard for everyone,” says Karen Jensen, founder of the “Teen Librarian Toolbox” blog. “There is just as much difference between a 20-year-old, a 40-year-old, a 60-year-old as there is between a fifth grader and a twelfth grader. I wish libraries did more to help patrons navigate adult collections. A New Adult category would help everyone.”

As Summers says, for many teens, seemingly “adult” experiences aren’t limited to adulthood. YA has always engaged with tough topics, and young protagonists deal with intense situations, just like teens do in real life.

“Teens are going through some really heavy things and want to see these things reflected in their lives—and I think feel better when they know that their lives are reflected on the pages,” Goodman says. “So what some may call crossover is us just really being realistic.”

Publishers bear this in mind when considering the serious themes in teen titles. “There is so much of the adult world that manages to trickle down to teens these days, so having books, characters, and voices that speak to those experiences or help a younger reader process on their own terms is an important part of what YA books can do,” Nolan says.

Nataraj says that college students, particularly freshmen, are engaged in self-reflection, and that comes through in the YA books they choose, both for recreational reading and for research projects.

Janet Hilbun teaches a graduate school class on children’s and YA literature at the University of North Texas. “[My students] really like YA, but they don’t really want to read about high school anymore,” she says. “And they don’t want to read about mothers with kids and marriage problems. They want the college, they want the early dating…..As one student put it, they want to read about people that are in the same season of their life as they are.”

Crossover YA can also appeal to young adults who put recreational reading on hold during their intensive high school and college years, Hilbun says. “They sometimes miss these books and they don’t get back to them until after they graduate from college.”

So, who are crossover YA books for? Everyone.

“They leave open the door for different experiences and perspectives without dictating what degree of either the reader should have,” Nolan says.

And though teens are legally adults at 18, many don’t identify with being grown up. “Who feels like an adult when they’re 19 or 20?” Goodman says. “Not many people do.”

Katy Hershberger is the senior editor for YA at School Library Journal.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!