"Troublemaker for Justice" Brings the Forgotten Legacy of Civil Rights Leader Bayard Rustin into the Light

Troublemaker for Justice uncovers the life of civil rights leader Bayard Rustin, whose legacy has long been ignored because he was openly gay.

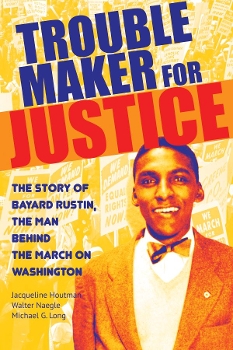

Outside of the famous figures of the civil rights movement such as Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, there were thousands of people who worked diligently behind the scenes to make the movement successful, although history often overlooks them. Bayard Rustin was one of those people. From the rides of the Journey of Reconciliation to the organization of the March on Washingt on, Bayard Rustin relied on his Quaker upbringing to bring about change in a nonviolent manner. Beyond the civil rights movement of the 1960s, Rustin continued to be a voice for the rights of those not heard loudly, such as immigrants and refugees to the United States, the poor, women, and those in the LGBQT community. Troublemaker for Justice is the product of a collaboration of three authors: Michael G. Long, an associate professor at Elizabethtown College; Walter Naegle, the former partner of Bayard Rustin; and Jacqueline Houtman, a Quaker and experienced writer for children. The three authors spoke with SLJ about their journey to producing Troublemaker for Justice and the important message Bayard Rustin’s story has for young people of today.

on, Bayard Rustin relied on his Quaker upbringing to bring about change in a nonviolent manner. Beyond the civil rights movement of the 1960s, Rustin continued to be a voice for the rights of those not heard loudly, such as immigrants and refugees to the United States, the poor, women, and those in the LGBQT community. Troublemaker for Justice is the product of a collaboration of three authors: Michael G. Long, an associate professor at Elizabethtown College; Walter Naegle, the former partner of Bayard Rustin; and Jacqueline Houtman, a Quaker and experienced writer for children. The three authors spoke with SLJ about their journey to producing Troublemaker for Justice and the important message Bayard Rustin’s story has for young people of today.

Michelle Kornberger: Tell us about the journey to write this book.

Michael G. Long: My interest in writing this book grew out of my work on I Must Resist: Bayard Rustin's Life in Letters. After I finished editing Resist, I was simply amazed at Rustin's fervent commitments to peace and justice, equality and dignity, and direct action and democracy. I was so impressed that I wanted to write a book that would be accessible to my younger son Nate (now 13), his friends, and young adults everywhere. The heroes they learn about in school are often presidents, generals, and leaders in industry and business. I wanted to offer them another model of greatness—someone who devoted his life to fighting for the rights of minorities and people whose voices are often ignored in mainstream society.

Walter Naegle: I was brought on board by Michael. He asked me to make suggestions/edits on his draft and it grew into a collaboration of three people with different and unique things to offer.

Jacqueline Houtman: As a Quaker, I knew a little about Bayard Rustin and his activism. When I was asked to join the project, I was eager to learn more about him and to make his story more widely known. I used my experience writing for children to help make the book more accessible and engaging for younger readers. Collaborating with Walter and Mike was a pleasure, and we each had our own perspectives and skills to contribute.

MK: Why do you think now is an important time to share Rustin's story with young adult readers?

WN: Many of today’s youngsters are seeking to create a more just world at a time when it appears that undemocratic forces are rising. Bayard's life and work provide an inspirational example of how to organize and fight for progress even during dark, chaotic times.

MGL: Now is the time to revisit Rustin's story with young adult readers because civil rights, LGBTQ rights, and the rights of poor people are under assault by leaders in political society. Despite claims about the economy doing so well, these leaders want to cut programs and policies, and reverse court decisions that have long protected the vulnerable members of society—the ones for whom Rustin fought so hard.

|

Michael G. Long |

Rustin’s story is also important at this point because it shows us not only the importance of protesting for rights but the need to protest in effective ways—through nonviolent direct action campaigns designed to change public policy so that it will better serve those who have been marginalized in our society. Protest is more popular now than it's been in fifty years, and Rustin's story can help us understand and carry out protests that are smart and effective.

JH: Young people are realizing that they have the power to change the world. Look at Malala Yousafzai, the youngest winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. Look at Greta Thunberg and her activism against climate change. Look at the survivors of the Parkland shooting, and the March for Our Lives, where all of the speakers were of high school age and younger. Young people see a lot of problems in this world, and we hope that, by learning from Bayard’s life and accomplishments, they will be empowered to act and make a difference.

MK: What is the most important message you want young adult readers to take away from Troublemaker for Justice?

WN: Be true to yourself, your identity, and your principles. Be tolerant, patient, and compassionate. Let love rule the day.

JH: I hope they learn that the struggle for civil rights did not rely on just a few people. They are taught about Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks, but there were thousands more who worked, struggled, suffered, and contributed their gifts to the civil rights movement. Most of their names are lost to history. Everyone has something that they can do to promote social justice. I would like them to find their gifts, listen to their hearts, and participate in activism for causes about which they are passionate.

MGL: I would like young adult readers to understand that obedience is the heart of political power—that the more we obey unjust leaders, the more power they will have to commit more injustices. Rustin understood that by withdrawing our cooperation with unjust political leaders, we can make them lose power and indeed return power to the people. Young adults have often been trained to be obedient—to stand up, put their hands over their hearts, and pledge allegiance to the flag, for example. Rustin teaches us that a posture of obedience is insufficient for being a good citizen. Sometimes good citizens need to resist the powers that be for the sake of peace and justice.

MK: Bayard was influenced by his grandmother’s Quaker values. Tell us more about this.

JH: The central belief of Quakerism is “that of God in every person,” or as Bayard put it, “the concept of a single human family and the belief that all members of that family are equal.” [His grandmother] Julia Rustin taught Bayard the value of nonviolence and the importance of social justice, both of which are integral to Quaker values. Bayard believed that all discrimination was wrong, and throughout his life, he fought for the rights of all humans. His work extended beyond civil rights to the labor movement, support for refugees, antinuclear activism, fighting for human rights and democracy around the world, and (later in his life) to gay rights. His activism arose from his belief in the equality of every person.

WN: Quakers believe in the oneness of the human family, in equality, and in that "still small voice" (sometimes described as conscience) that resides in all of us. Julia Davis Rustin embodied these principles and taught them to Bayard through her example and counsel.

MGL: As a youngster, Rustin was also influenced by the values of the black church he attended in West Chester, PA. Historically, black churches have consistently claimed that we are made to be free—to be free from slavery, from discrimination, from anything that oppresses us. Rustin took this to heart and enacted this belief throughout his life. Like his black church, Rustin also believed that human freedom is a gift for which we must struggle every day of our lives and that all people deserve freedom right here and right now.

MK: Bayard Rustin organized freedom rides years before Rosa Parks infamously refused to give up her seat on a bus to a white person. Why do you think these initial rides receive little credit as an early part of the civil rights movement?

MGL: These initial rides in 1947—known as the Journey of Reconciliation—revealed the bravery and courage of the young adults who participated in them. Part of the reason they receive little credit is that they occurred before the civil rights movement took off under the leadership of Dr. King. The life and work of Dr. King has always received much more attention than the early campaigns that paved the way for his emergence.

Another reason that they receive little credit is that, while they were incredibly dangerous, they did not result in the type of vicious attacks suffered by the Freedom Riders in 1961—the type of assaults that attract the media. But let's make no mistake about it: The Freedom Riders stood on the tall shoulders of Rustin and his colleagues in the Journey of Reconciliation.

WN: The early freedom rides were small, usually not reported in the

|

Walter Naegle |

mainstream press, and before the advent of television. Scholars are now recognizing the significance of the Journey of Reconciliation (1947) as an important milestone, partly because it sought to highlight non-compliance with the Supreme Court's decision in Morgan vs. Virginia (1946), and partly because of Bayard's published account of his experiences on a chain gang, the result of his arrest in North Carolina.

JH: Bayard’s first arrest on a bus for sitting in the whites only section (1942) was one of the inspirations for the Journey of Reconciliation five years later. Rosa Parks was arrested in 1955 and the Freedom Rides took place in 1961. One of the biggest changes over that period was the ability of the media, especially television, to influence public opinion. Bayard knew that television could be a powerful tool. Reading about a violent incident in the newspaper was one thing. Television brought the blood and brutality into people’s living rooms. Bayard noted that “the camera laid bare the Southern lies” and helped to sway public opinions. That influence is stronger (and faster) today, with cell phone cameras and social media.

MK: Bayard organized and spoke at the March on Washington yet receives little credit. Why?

JH: That’s the question we ask in the opening chapter and attempted to answer in the rest of the book.

MGL: Rustin's role was largely behind-the-scenes, and those who labor mostly in the shadows rarely receive the credit they deserve. Nevertheless, you are right to note that Rustin spoke at the March. In fact, he led the massive crowd in endorsing the demands of the March. (By the way, you can easily find video clips of Rustin thrusting his fist in the air as he read these demands.) But when the media revisits the March, they usually focus on Dr. King's "I Have a Dream" speech. Given the power and passion of this speech, the focus on it is understandable. Plus, King's delivery was simply masterful, a model for public speaking. My point here is that in our remembrances of the March, Dr. King usually overshadows Rustin and every other leader at the March.

But let me add this: civil rights leaders like Roy Wilkins of the NAACP were deeply concerned that Rustin's identity as a gay man would harm the March. In 1963, homosexuality was often considered criminal, immoral, and a symptom of mental illness. Wilkins and others believed that the enemies of the March would publicize Rustin's homosexuality as a way of depicting the March as the product of people whose values were anti-American. Before 1963, Dr. King was also fearful that Rustin's identity as a gay man would hurt the civil rights movement. At one point, Dr. King was so fearful of this that he removed Rustin from his inner circle of advisors.

Rustin has often been ignored by students of history because civil rights leaders, at one point or another, tried to keep Rustin out of sight, out of mind—in the shadows of their greatness. Doing so, they revealed their weakness. Rustin was a brilliant strategist whose dreams and planning helped to make the civil rights movement as successful as it was. He was, as Vernon Jordan has called him, the "intellectual bank" of the movement—the place where activists went to withdraw ideas and plans to win their fights.

WN: He does receive credit nowadays, although it took a long time for that to happen. He was marginalized largely because he was gay and open about it. He delivered the demands at the March, not quite the same thing as a speech. Also, all the leaders spoke but were overshadowed by Dr. King's brilliant words.

MK: How did Bayard influence Dr. King?

MGL: When Rustin first met him in Montgomery, Alabama, Dr. King was not a pacifist. He had applied for a gun permit, and he had approved of armed bodyguards keeping watch over his family and their house. As one committed to nonviolence, Rustin was disappointed, if not appalled. Rustin believed that if civil rights activists engaged in armed conflict, they would be overwhelmed and slaughtered by the much more powerful police forces. For Rustin, getting rid of the guns was necessary to safeguard the lives of those in the movement. Rustin convinced Dr. King of the same, and the great civil rights leader soon devoted himself to nonviolence.

But Rustin also influenced Dr. King in another way. He convinced Dr. King that a commitment to nonviolence was not merely a strategy but an invitation to a way of life. Rustin helped Dr. King understand the need to be a pacifist—someone who is committed to peace at all times and in all places, someone who adopts peace as a way of life, someone who refuses to use force even for a good cause.

Beyond this, Rustin helped Dr. King understand the importance of strategy. Rustin once said that Dr. King could not organize vampires to go to a bloodbath. Dr. King excelled in expressing his dreams, but he needed a lot of help in making those dreams become real through concrete planning and strategy. This is what Rustin offered to Dr. King—the gift of strategic thinking. On this point, Rustin persuaded Dr. King to create the Southern Christian Leadership Conference—the civil rights organization that Dr. King led from 1957 to 1968.

Finally, Rustin influenced Dr. King's thoughts about the reach of the civil rights movement. It was Rustin who encouraged King to pay attention to freedom movements in India, Africa, and other places, and to connect the U.S. fight for civil rights with the worldwide struggle for human rights.

WN: I think he helped to convince Dr. King that nonviolence was more than a tactic, that it was a philosophy, a way of life. He drew up the founding papers for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference that became Dr. King's home base until his death. He helped King to move in the direction of speaking about economic inequality as the next step in the struggle for African Americans.

|

Jacqueline Houtman |

JH: There were practical things, such as organization and strategy, as well as the philosophy and tactics of nonviolent direct action, as was practiced by Gandhi. He also served as an advisor and sounding board. He was a mentor to King who, in turn, mentored many others in the movement.

MK: How did Bayard continue to be involved in the civil rights movement post 1960’s?

WN: He continued to play a role as the founder of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, an organization working to build alliances between black workers and the labor movement. He chaired the Recruitment and Training Program (RTP) which was designed to help minority youngsters gain access to union apprenticeships. He was part of the Black Leadership Forum. He also worked on behalf of civil rights for all people, including immigrants and refugees coming to the U.S., women, and the LGBTQ community.

MGL: After the assassination of Dr. King in 1968, Rustin devoted his life to a cause he had started even before King died—a reduction of poverty in the United States. As head of the A. Phillip Randolph Institute, Rustin lobbied government leaders to develop policies that would lift people out of poverty and provide them with the tools they needed to enjoy life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Rustin also devoted many hours to fighting for the rights of Jewish people in the Soviet Union, for material assistance for refugees across the world, and for the right of LGBT people to lead lives free of discrimination and violence.

JH: “Civil Rights” to Bayard was just a part of the human rights for which he fought his whole life. These included labor rights, the rights of refugees, and the promotion of democracy around the world. He seemed to work for a huge variety of causes, but to Bayard, it didn’t matter which group was being discriminated against—all discrimination was wrong.

MK: How has Bayard been acknowledged for his contributions to the civil rights movement?

WN: He now has a secure place in the history books as one of the leading tacticians/strategists that moved the struggle forward. He is recognized as the master organizer of some of the most important demonstrations/protests, including the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom, and the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. He was awarded The Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013 for his contributions to the civil rights struggle.

JH: There are streets, schools, and organizations named after him. Books, plays, and films portray his life and participation in the civil rights movement. The most important acknowledgment, I think, was the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013. Here we had Barack Obama, our first African American president, bestowing the medal. And for the first time, the posthumous award was accepted by an honoree’s surviving same-sex partner, Walter Naegle. That fact is evidence of some amazing progress, but there is still so much more to do.

MGL: School libraries are beginning to share his courageous story with hundreds of thousands of young people!

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!