Tiffany D. Jackson Empowers Teens Through Gripping Page-Turners

Beloved YA author Tiffany D. Jackson, winner of this year’s Margaret A. Edwards Award, speaks to SLJ about the award, her expansive work, and how real life influences her stories.

|

Photo by Kolin Mendez |

Beloved YA author Tiffany D. Jackson, winner of this year’s Margaret A. Edwards Award, illuminates characters who are struggling with the distance between where they feel they are in relation to the world and where they feel they want to be. Her work showcases movement and variability not only in location, but also in style, theme, format, genre, and collaboration.

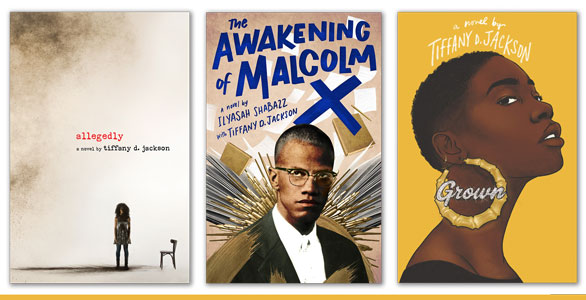

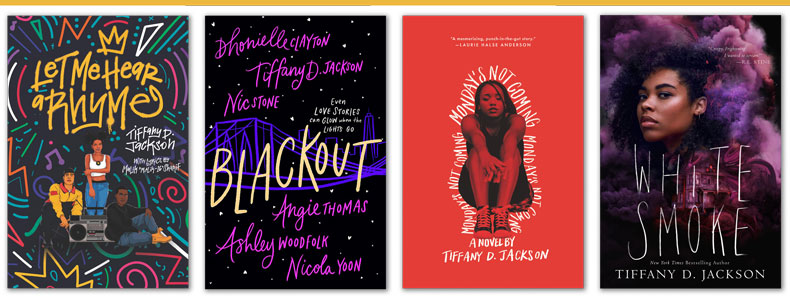

The Edwards Award, given since 1988 by the Young Adult Library Services Association (YALSA) “for significant and lasting contribution to young adult literature,” celebrates literary works that help teens become self-aware and address important questions about their roles in all sorts of relationships, along with society and the world. The six novels and one short story by Jackson recognized for this year’s award—Allegedly (2017), Monday’s Not Coming (2018), Let Me Hear a Rhyme (2019), Grown (2020), The Awakening of Malcolm X (cowritten with Ilyasah Shabazz, 2021), “The Long Walk” (from the collaborative work Blackout, 2021), and White Smoke (2021)—are tied together by exquisite writing and recognizable voice, spanning genres and age ranges with signature exuberance and intensity.

Nobody would try to pin Jackson down in any way, both in her writing and in real life. A Brooklyn native, she has a nomadic spirit that keeps her on the move around the world. “Brooklyn will always be the center of the world to me forever and ever,” Jackson says, speaking from Atlanta. “But I also feel that travel has had such a huge impact on my life and has made me almost breathe differently, so that’s why I continue to do it. And when you come back to your hometown, you look at the streets differently. You look at the people who are driving next to you differently. You appreciate the way they dress, their certain religions and even their subcultures, in a sense, you appreciate that so much more.” This love of adventure brings vibrancy and perspective to her stories; Jackson notes that “[when] you explore, the world opens up to you, and eases your jadedness about your own world.”

|

|

|

Her characters, such as Mary from Allegedly, Claudia from Monday’s Not Coming, and Enchanted from Grown, speak to teens who are trying to bridge the gap between where they are and where they want to go. “I think that is literally the story of every teen’s life,” Jackson says. “That is the definition of teenhood, deciding who you want to be and deciding how to get there. I don’t think I can think of any person that didn’t have that question raised themselves, and I think watching those types of questions play out in real time will help teens ultimately make their own decisions.”

Jackson has a deep film background, including degrees from Howard University and The New School, and over a decade in the industry. Her scene-focused narrative organization lends itself to sharp characterizations and layered plotlines, and her authenticity and directness engage teens with an often unflinching reality. Her wide-ranging impact and broad literary prowess are clear in the seven works the committee chose to highlight. They are often unexpectedly twisty, always emotionally impactful, and undeniably thought-provoking. The Awakening of Malcolm X, a reality-based and detailed historical novel about the famous activist’s incarcerated years, cowritten with his daughter, is no less powerful for its lack of surprise turns. Monday’s Not Coming, though, Jackson’s sophomore title, puts the wrench right up front—Claudia’s best friend, Monday, is missing, and absolutely no one else seems to care. Why?

Jackson can create palpable suspense in short order; her story “The Long Walk” begins the collaboratively authored Blackout as two teens navigate their complicated feelings and a New York City power outage. Sometimes Jackson’s stories will sneak up on you, too, like her first book, Allegedly , which follows Mary, a teen who is in a group home because of a deadly incident from her childhood, and is desperate to find a way to get the system to let her keep the child she’s carrying. It’s a haunting story with a wicked twist. Mary is also the character Jackson says has stuck with her the most. “I often think of her story, and stories like Mary’s; I think about the girls that are in juvenile halls or in foster care. I think about them a lot more than I think about any other characters. I want kids to think about these characters, too.”

Mary’s tale was loosely inspired by a real story, as are many of Jackson’s books. “I guess that’s my jam,” she says. “I don’t feel that our stories should be a warning message all the time. I think they also should be a learning opportunity for [young readers] to identify the problem themselves. Like, ‘Oh, wait, that’s not okay.’ And I fully trust kids to do that, but they need to have the tools and opportunities to do that within a safe environment, which is books.”

Another excellent example of this approach is Jackson’s novel Grown, which follows talented teen vocalist Enchanted as she gets caught in the web of a manipulative, grooming older man. At once a warning, a clear-eyed lesson, a gripping thriller, and a scathing critique of the societal tendency to blame girls for their own abuse, the novel is, Jackson says, a tool she herself could have benefited from during her teenage years as someone who was in an age-inappropriate relationship. “That was the biggest secret I ever had. But if I had had a book that showed me the end result of what that could look like, and if I had a story that really showed me how someone can prey upon your vulnerabilities, I think I would have chosen a different course. I would have realized that something was wrong. I’m hoping that teens process their own emotions and their own questions through stories that really speak to their circumstances.”

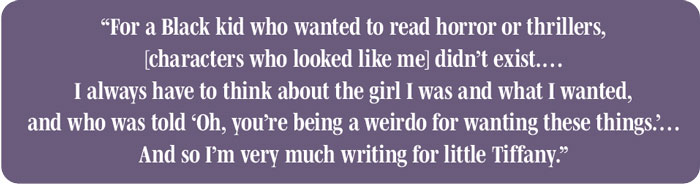

Grown isn’t the only title Jackson has written at least partially for the person she thinks of as her younger self, “little Tiffany.” She recalls being a young reader who struggled to find the right books, making the leap from R.L. Stine to Stephen King, with little in between. “For a Black kid who wanted to read horror or thrillers, [characters who looked like me] didn’t exist. It was very rare.” Though her grandmother introduced her to poetry, which she describes as a “soft place” for a “pretty intense reader,” she says that now when she sits down to write horror and thrillers for young people, “I always have to think about the girl I was and what I wanted, and who was told ‘Oh, you’re being a weirdo for wanting these things.’ And then later on, learn that, oh, no, there’s tons of [kids] out there that want the same thing. And so I’m very much writing for little Tiffany.”

Most of Jackson’s works lean more on suspenseful real-world situations than supernatural scares, like Let Me Hear a Rhyme, which focuses on three teens who pretend their deceased hip-hop artist friend is still alive in order to lure his killer out of the shadows. But personally, one wonders if “little Tiffany” would be especially fond of White Smoke, a trippy haunted house tale that tackles gentrification and mental health alongside a bedbug phobia (which, yes, lends itself to exactly the sort of shudder-inducing feelings one would expect from Stine or King). Too recent to be included on the Edwards list but also worth a mention here is Jackson’s The Weight of Blood (2022), an incredibly insightful homage to King’s famous teen in Carrie (1974).

As for current Tiffany, what is she reading now and what sorts of books have been lighting up her brain lately? Her most recent read at the time of this interview was Homecoming by Dr. Thema Bryant (Tarcher, 2022), a nonfiction title that discusses healing from trauma and reconnecting with oneself for a more meaningful experience of life. “I think more people, including kids, should read self-help books [and] at an early age,” Jackson says. “We all need some sort of solace and rest and self-care. When people ask me, ‘If you could tell your younger self something, what would you say?’ I would say ‘It’ll be okay. Focus on yourself. Focus on breathing. Take yoga.’ I wish more people told teens to focus on self-care, because that’s going to carry you through life more than anything else. How can I write and pour my heart onto the page when I’m depleted?”

The Edwards Award win seems to be refueling Jackson’s drive, too: “I’m truly honored to win this because I often find myself at the beginning of every book, and at the beginning of every season, saying, ‘Am I doing the right thing? Am I making an impact?’ I question myself a lot. Even at the beginning of this year, I was trying to decide, should I continue writing? Do I belong here anymore? And then, while I was questioning myself, I got this call about this award, and it really lifted my spirits in a lot of ways.”

The Edwards Award win seems to be refueling Jackson’s drive, too: “I’m truly honored to win this because I often find myself at the beginning of every book, and at the beginning of every season, saying, ‘Am I doing the right thing? Am I making an impact?’ I question myself a lot. Even at the beginning of this year, I was trying to decide, should I continue writing? Do I belong here anymore? And then, while I was questioning myself, I got this call about this award, and it really lifted my spirits in a lot of ways.”

For what’s coming next, Jackson has two new books slated for publication in 2025. In July, her first middle grade title will be released. Blood in the Water follows a young Black girl summering on Martha’s Vineyard and trying to solve a murder mystery. How did she adjust her writing to a middle grade level? “I think what I’ve nailed it down to is that middle graders are learning about the world, and teenagers are learning about themselves and also learning that people aren’t perfect.” Her new YA title, The Scammer, coming in October, takes a true story (a 2010 cultlike situation on the campus of Sarah Lawrence College) and kaleidoscopes it into something new, following a college freshman whose roommate’s older brother’s manipulative schemes are tied to a dangerous disappearance. “I remember my own college experience,” Jackson says. “We literally were teens walking into the adult world with just basically all the guidance and love from our parents. It’s such a vulnerable point in our lives that of course predators would prey especially on freshmen living on college campuses.”

Jackson’s Edwards Award puts her in the esteemed company of writers like Walter Dean Myers, Judy Blume, Jacqueline Woodson, and Laurie Halse Anderson. It’s a truly deserving honor for an author whose work places unforgettable, genuine characters into formative, suspenseful situations in which they have to ask big questions—and find out the answers, for better or worse. Luckily for young readers everywhere, Jackson isn’t done yet. “I’m deliriously honored about this, and just stunned, because I still feel like I have so much work to do.”

Allie Stevens is a librarian in south Arkansas.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!