Writing for Change: Margaret A. Edwards Award Winner Kekla Magoon in Conversation with Ibi Zoboi

Magoon spoke with best-selling author Ibi Zoboi about the book that’s closest to her heart, forming her identity while reckoning with history, and being a writer ahead of her time.

|

Kekla Magoon photograph by Josh Kuckens |

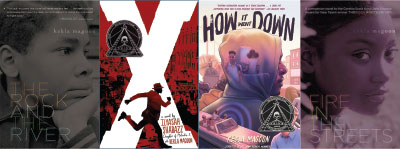

The Margaret A. Edwards Award honors an author and a body of work that have made a “significant and lasting contribution to young adult literature.” It is given annually by the Young Adult Library Services Association, a division of the American Library Association, and is sponsored by SLJ. In selecting Kekla Magoon and her books X: A Novel (cowritten by Ilyasah Shabazz), How It Went Down, The Rock and the River, and Fire in the Streets, the 2021 committee noted, “Magoon’s books inspire teen readers and future authors to seek truth and remind readers of their moral duty to confront racism, white supremacy, and injustice.” From Magoon’s perspective, her books help her understand her place in the world and allow readers to understand theirs too. She spoke with best-selling author Ibi Zoboi about the book that’s closest to her heart, forming her identity while reckoning with history, and being a writer ahead of her time. These are edited excerpts from their conversation.

Ibi Zoboi I always say as a writer, that I would want to be recognized for a body of work. Although any one book can stand out, I think there is something to be said about getting a nod from whomever to say that you’ve been doing this for a while. You’ve done a lot, and here is your sticker. Here’s your award. And it’s to recognize that you are part of a tradition. You are a part of an industry who is contributing a lot to the industry.

What do you think about being honored for several books rather than one book over the course of your career?

Kekla Magoon A lot of my books, even though I am writing history and contemporary fiction and nonfiction, have an underlying core set of issues that I’m always exploring in terms of social justice, a lot about identity. And about how you as an individual connect to a broader movement or find your place in the world—as a person, but also as someone who tries to make a difference or tries to make the world a better place. And all the different stories I write have threads that connect to those issues, and the more that I publish, the clearer it is that there is that unifying message underneath everything.

To feel like other people recognize that, to feel like that is something tangible beyond my own mind, feels weighty. Not like a pressure, but a heaviness of, This is significant. I have done something that’s important and that is a feeling that I don’t even know how to describe.

Zoboi Would you rather the books do the work for you, where you can sit back and worry about the writing? Or are you the type of author who likes to be out there being a bullhorn for your books and your ideas?

Magoon I tend to think of it as a cycle. I have the idea. I’m pecking away at my computer, having no real clear sense of if it’s ever going to reach an audience. That’s the part that is me generating the book. And it goes through the whole process of publication and revision and then it goes out. I have released it into the wild and it’s going to do what it’s going to do out there.

In that sense, I do think that once the book is published, it’s doing work beyond me. I’m never going to know whose world was changed or touched by that reading experience. But I think of myself, as the author, as trying to follow the books, and that’s why I love meeting readers. When I go out there, I get to participate in the conversation that I hope that the books are sparking in different communities, in the minds of the individual readers, in classrooms, and so on.

I feel like I am sparking something, that just by having put the words on the page that I am the engine behind the books, and then the books are going on their way. That’s why it helps me to think of it as a cycle, where I’m energizing the book, which then goes and energizes the readers, who then energize me in return. It’s a continuous process of learning and growing and giving and receiving.

Zoboi Let’s talk a little bit about you as an artist. I like to use “artist” because it’s all-encompassing. It’s not just that you’re a writer putting words on the page and dreaming up a story. You, as an artist, are connecting other things in the world. You are probably incorporating other art forms in your writing process.

When do you think you became an artist? Even though there are authors who start writing in adulthood, I like to believe that they were artists when they were children. Is that true for you?

Magoon I think I was a storyteller all along. One of my favorite ways to play when I was a kid was collecting all of the dolls, including the G.I. Joes and whatever other things my brother had, down in the basement, and creating stories and narratives and having characters interact, but none of it was on the page.

I think somewhere around middle school I lost some self-confidence and some self-esteem, as often happens in middle school. To see myself as an artist at age 12 would not have been possible, I don’t think.

But at that age, I had a diary under my pillow and I would write in it. I think that I was always using creativity and story and art as a way of celebrating, but then also as a way of coping, and as a way of trying to find my place in the world. So I do think that the types of stories that I write now can be traced back to some of those feelings of, I don’t know who I am. I don’t know how I fit in the world. I don’t know how to be likable. I don’t know how to be really myself and be appreciated for that.

So now, as a person with much more self-confidence and understanding of my own skills and talents, I still explore those questions in fiction, and especially in fiction for kids at that age where I was most vulnerable.

[WATCH: Kekla Magoon Talks to Ibi Zoboi About Family, Identity, and Diverse Books]

Zoboi You have a couple of books in the space of the Civil Rights and the Black Power movements. What is it about that time period that you are drawn to, especially considering your identity?

Magoon I am continually forming my identity as a Black woman, continually forming my identity as a Black American. And part of that for me is looking at where we’ve been and how we got to where we are. I grew up loving historical fiction and I read any Civil Rights book I could get my hands on. My favorite book of all time is Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry by Mildred D. Taylor.

I learned in school that the Civil Rights movement solved racism. Essentially, that is what we were taught, and yet that’s not my lived experience. So that cognitive dissonance was troubling to me for a long time, particularly when I learned a little bit about the Black Panther Party, that they did so much work to defend the community. When I was learning this, it really fueled my desire to tell these stories, because I didn’t want young people to struggle with that cognitive dissonance that I had been struggling with, where we say we solved this in the Sixties, and yet we’re still watching the news every night and seeing another Black person killed.

So for me, choosing the topics that I choose is about learning and understanding that history, so that I can understand my place in the world today, and how I can be someone who helps make the world an actually better place as opposed to the better place we claim that it is.

Zoboi Out of all of your books, which one captures who you were as a child? I know your social justice books are a heart project, but a book that really tells the world, This is who Kekla Magoon was at 12 or at 16 is another kind of heart book.

Magoon The most autobiographical of my fiction is Camo Girl. Ella is in sixth grade. She’s being bullied by a boy. He’s putting things in her hair knowing she can’t find them until she goes to sleep later that night. These are things that happened to me.

And that sense of feeling different, of wanting to fit in and not quite understanding how. Not really wanting to change yourself to fit in, but also wanting to be different. The whole stew of identity struggle that I was going through at that time, some of which persists to this day in terms of, I always want to be myself. I want to be liked for who I am. I don’t want to change myself in order to be liked, but I also don’t always know how to make friends when I’m just being me.

That was definitely the book that was closest to my heart. It felt good to feel like, I’m going to offer something to another sixth grade girl who feels lonely and confused and wants to connect but doesn’t quite know how. To feel like I was offering that was powerful.

|

Bearing Witness to Trauma, TriumphKEKLA MAGOON’S body of work that was selected for the Edwards Award includes her 2009 debut novel, The Rock and the River, and three other titles published no less than five years ago. The committee remarked: "Kekla Magoon’s powerful prose and complex characters enrich literature for young adults by bearing witness to the trauma and triumph of the American Civil Rights Movement. In X, co-authored by Malcolm X’s daughter, Ilyasah Shabazz, Magoon depicts Malcolm Little’s struggle to overcome unfavorable circumstances to transform into legendary Civil Rights leader, Malcolm X. In The Rock and the River and its companion novel, Fire in the Streets, two Black teens, Sam and Maxie, lose faith in peaceful protest and civil disobedience and embrace more aggressive action. How It Went Down, the story of a senseless shooting of an African American teen by a white man, illustrates the persistence of racial violence in America." |

Zoboi Here’s another question, an author-to-author type of question. We’ve heard these conversations, we’ve been part of these conversations, in terms of our social justice or trauma books getting more accolades or more attention or they sell more or sell for more, versus our joyous or quieter books.

What I want to ask on a personal note is, Which kind of book is more cathartic to you? Which feels the best while you’re writing it, and when it’s out in the world? Is the history/social justice book? Or is it the book like Camo Girl and the “Robyn Hoodlum” series, where you’re creating a character who is just fun and just going through identity issues, and it doesn’t have to be about changing the world?

Magoon I think in a way, the heavy trauma stuff comes easier to me. Like writing How it Went Down, writing Light It Up. There’s complexity to those narratives, but I have no trouble accessing that kind of content, because I’m constantly thinking about Race in America, capital R, capital A. I’m constantly trying to engage with it, understand, and help other people gain a more nuanced and complex understanding of that.

The “Robyn Hoodlum” series was like pulling teeth to be imaginative in that way, to be expansive in that way, to have that big, long-arc thinking. With The Season of Styx Malone, too. Sweet, fun, charming. Boys in the summer. It’s an adventure. In some ways that’s more satisfying writing, because it doesn’t come as easily. It’s more of a challenge. Because I think that it does push at the expectation that the experience of Blackness is defined by trauma.

I enjoy and feel more satisfied and feel like I am advancing a different aspect of the conversation when I’m writing fantasy, when I’m writing realistic fiction that’s lighthearted and fun. I would not say one is more important to me than the other, because they are incredible conversations that I have been a part of.

Zoboi I admire that and I aspire to that in terms of having a body of work, and so much range that your books are in conversation with each other, you know? You can’t say that Kekla only writes Black pain. I love that aspect of any writer, where you cannot box them in and say they only write this sort of thing. It just speaks to the nuance of who you are as a person and an artist.

When someone asked me this question, I was stumped. And I was like, wow, that is a great question. I don’t ask it to other writers all the time, but I’m going to ask you. Do you prefer to be a writer of your time or ahead of your time?

Magoon If I’m choosing one of the two, I would choose ahead of my time, which is where I feel like I live. There are things that people are writing today that I had written about five years ago.

I like the idea that I’m challenging people. That I am asking them to step into something that they’re not quite ready for. Because as soon as people become ready for it, it’s there.

If there are books that I’m writing that are being read by 12-, 13-, 14-year-olds who will in some way be positively impacted by that work, and do something systemic to actually change something, whether they’re bold enough to run for office, whether they start a nonprofit organization, whether they become the fastest long-distance runner in history because they persevered, whatever.

There’s all these ways that we can be and do things of import in the world. I don’t need to prescribe what that’s going to be for my individual readers, but to feel like that work is happening behind the scenes is, to me, more important and more powerful than material recognition and limelight in the moment. I want that systemic change.

Ibi Zoboi’s novel American Street was a National Book Award finalist and a New York Times Notable Book. She is also the author of Pride, My Life as an Ice Cream Sandwich, and Punching the Air (with Yusef Salaam), and the editor of the anthology Black Enough.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!