During COVID, Libraries Prioritized Electronic Resources, Fiction | SLJ 2021 Spending Survey

The pandemic has significantly impacted school library budgets and spending this year. Here's what has changed.

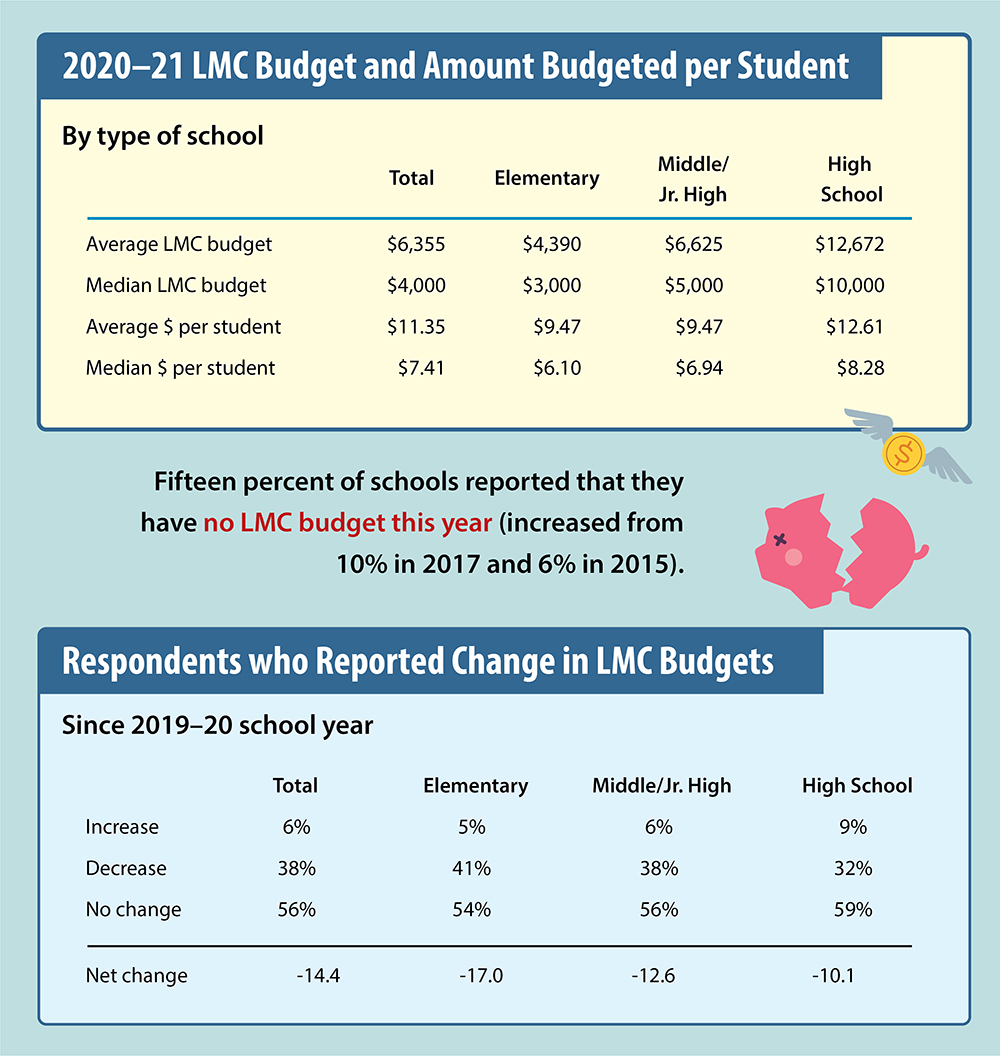

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have significantly impacted school library budgets and spending this year, according to the results of the latest SLJ School Library Budget and Spending Survey. About 38 percent of librarians reported a decrease in their library budget from 2019–20. Ten percent of those said their schools and districts shifted their funds away from libraries to cover other items of need connected with the pandemic, including distance learning materials, PPE, and additional janitorial services and cleaning supplies.

Many schools are looking for donations and other sources of funding to supplement their budget losses, while teachers are spending hundreds of dollars of their own money on items for the library and also searching for free and donated materials though sites such as DonorsChoose. The percentage of funding coming from book fairs decreased as well, from 17 percent in 2017-18 to 14 percent this year.

“Despite budget cuts, it is more imperative than ever for librarians to find ways to get resources into the hands of students, teachers, and families,” Kelsey Brooks, a librarian in San Angelo (TX) Independent School District, wrote in the open-ended section of the survey.

Crissy Brown, a librarian at Folsom Hills (CA) Elementary School, said, “I use as many free materials and supports as possible, as well as what the district buys for schools and teachers. I take book donations. I try to give the district any and all reasons to support the libraries.”

READ: Ahead of the Curve: School Librarians Innovate and Take on New Responsibilities | SLJ COVID-19 Survey

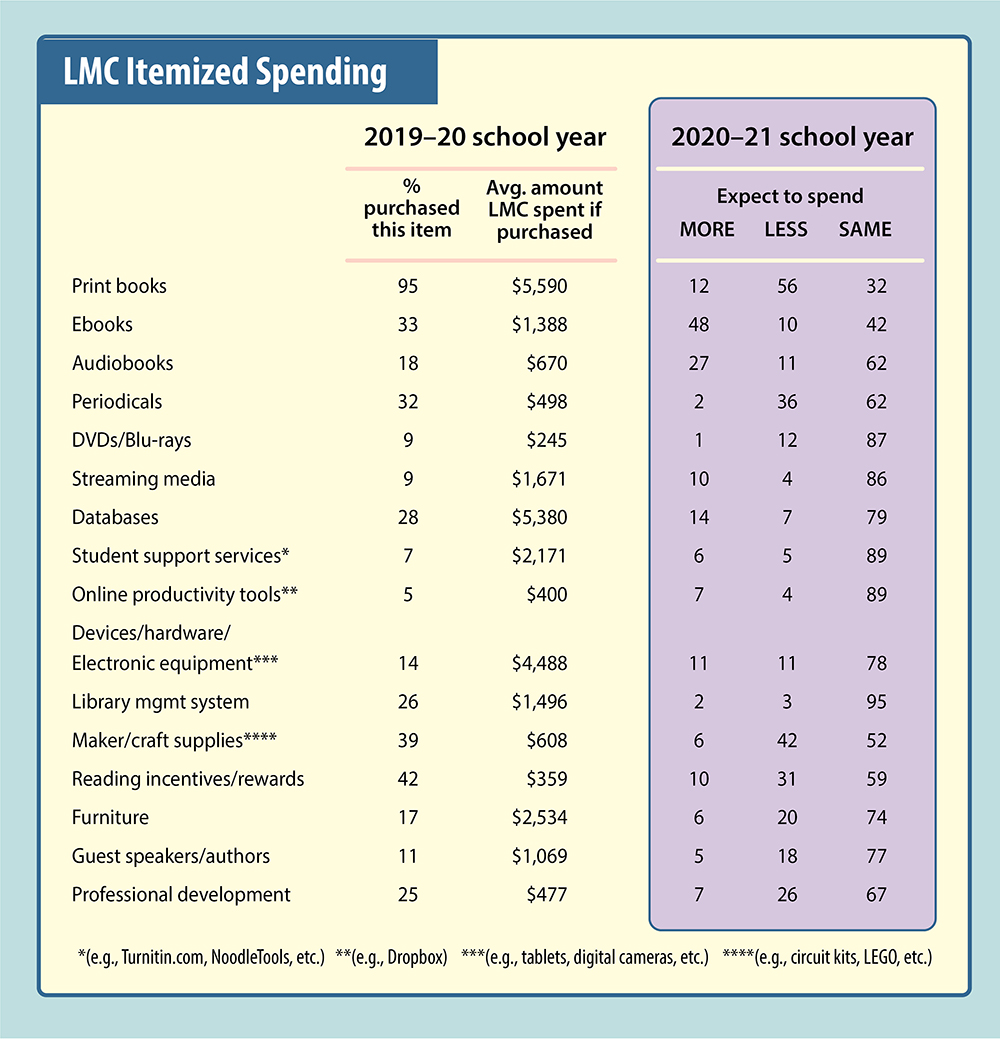

Nearly half of the respondents said they face restrictions on what they are allowed to spend their library media center (LMC) budget funds on this year; many said they are required to get approval before any purchases are made. Overall, many librarians plan to spend more this year on ebooks and audiobooks than last year, while also boosting their spending on fiction versus nonfiction.

Budget decreases and spending shifts

Schools are facing a significant decline in funds for their libraries this year. The average LMC budget for this academic year is $6,355, down 14.4 percent from 2019–20. The average budget amount per student is $11.35, which is nine percent less than the per student budget reported two years ago. Fifteen percent of schools have no LMC budget this year.

“I am not sure exactly where the funds will be spent, but they are not being spent on anything library related,” wrote Traci Williams, a media specialist at Stockbridge (GA) Middle School, who said her school has no library budget this year.

Private schools on average have a higher LMC budget than public schools, and far fewer private schools had budget cuts than public schools. Private school LMC budgets on average were $10,120, which is 59 percent higher than the national average, but they also include a higher proportion of high schools. While 39 percent of public schools said they had a decrease in their LMC budget this year, only 25 percent of private schools reported a drop. Twenty percent of private schools had higher LMC budgets, while only five percent of public schools saw an increase.

Other sources and out-of-pocket spending

Many libraries are looking for other sources of funding this year to supplement their budget.

According to the survey results, just over half of the dollars spent by libraries (54 percent) come from a dedicated LMC budget. That’s down from 63 percent in 2015 and 58 percent in 2017.

Funding that does not derive from the LMC budget is coming from federal and state funds, book fairs, parent organizations, grants, and donations.

Twenty-eight percent of respondents said donations have decreased since a year ago, while only four percent noted an increase. Many librarians, about 20 percent, said they are trying new strategies for donations and fundraising, including online book fairs, applying for grants, and using DonorsChoose.

Some librarians said they are reaching out directly to families and local businesses to help support the library. “I am asking students to purchase their own books and asking for classroom book donations,” wrote Diane O’Nions, a librarian at Charyl Stockton Preparatory Academy in Brighton, MI.

Michelle Schaub, a media specialist at Monona Grove (WI) High School, said that she has “expanded my grant scope.” She also plans to collaborate with the public library for some community programming.

Book fairs are another source of income for many schools. About 88 percent of elementary schools held a book fair last year. With many students learning from home this year and widespread safety concerns about any kind of group gathering, this year many schools said they aren’t planning to have any. About 46 percent of respondents said they intend to hold a virtual book fair, while only 11 percent said they plan to hold an in-person book fair. Among elementary schools, 57 percent plan to hold a virtual book fair, and 12 percent an in-person fair.

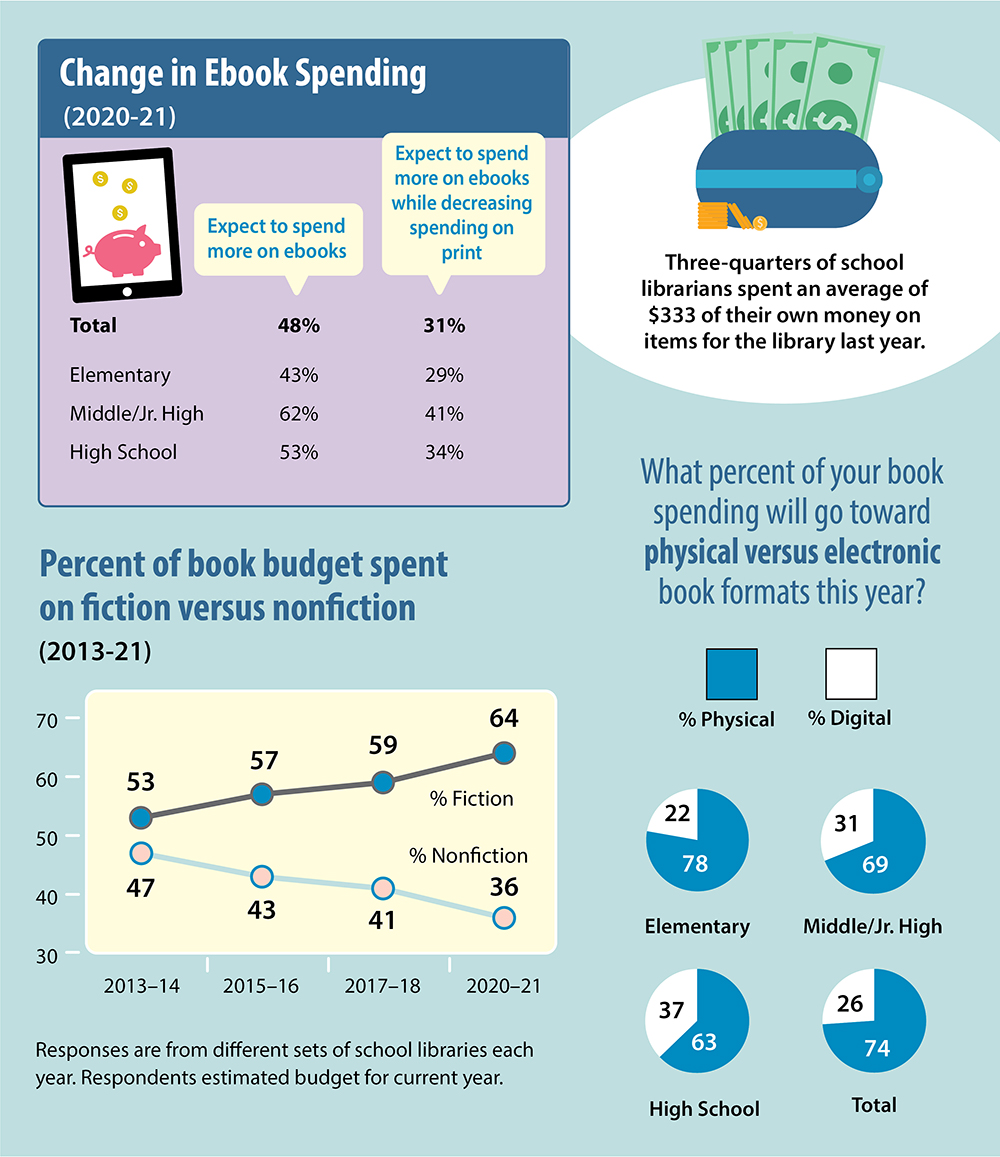

Librarians all over the country are spending their own money on items for the library. Three-quarters of school librarians reported that they spent an average of $333 of their own money last year, up from $304 in 2017–18. They spent it primarily on books as well as items such as art supplies and prizes.

More ebooks, fewer periodicals

About half of school librarians (48 percent) have restrictions on what they are allowed to spend their LMC budget on, no matter the grade level. Some librarians have been told by their school administration or district that they can only spend on ebooks this year. Many are allowed to buy circulating items with their budget, but rules vary for purchasing equipment, supplies, and technology.

“This year, I can only purchase digital items,” wrote Billie Gillespie, media specialist at Lakeview Middle School in Cortlandt, OH. “Funds have been shifting to purchase ebooks and audiobooks for the hybrid learning model. I have been instructed to not purchase any books with school money. [Books] have to come from a book fair or PTA donation.”

The majority of librarians’ spending on books is still going towards physical books. In total, 74 percent of spending on books is planned for physical books, while ebooks account for 26 percent. The percentage for digital books increases as grades go up.

While physical books still account for the bulk of spending, close to 60 percent of librarians expect to spend less on print books than they did last year. On average, librarians spent $5,590 on print books in 2019-20.

Nearly half of school libraries predict an increase in spending on ebooks this academic year, and 27 percent plan to spend more on audiobooks. A third of all librarians (33 percent) purchased ebooks last year and 18 percent purchased audiobooks. Middle schools are the most likely to anticipate spending more on ebooks and less on print.

Meanwhile, 36 percent of librarians expect to reduce spending on periodicals, and 31 percent are spending less on reading incentives and rewards. Forty-two percent of librarians also plan to decrease their spending on maker and craft supplies, 26 percent will spend less on professional development, and 18 percent will spend less on guest speakers/authors.

The percentage of spending on fiction has been trending upward since 2013. This year, funds spent on fiction rose five percent, to 64 percent of total budgets, while the amount spent on nonfiction fell to 36 percent, from 41 percent in 2017–18.

Many librarians believe that spending changes made during the pandemic will be permanent, especially the increased focus on ebooks and digital materials.

Unmet needs

Just over half of respondents report that there are specific needs they are unable to address because of a lack of funds. Many aren’t able to replace books that were lost or not returned when the school abruptly closed in the spring. Some wrote that they aren’t able to increase their selection of digital materials and ebooks, or update their nonfiction collections, because they don’t have enough funds.

“Although my official school budget has not changed, the additional funds I usually receive through fundraisers, like book fairs, no longer exist, so it’s a struggle to purchase the quantity of books I would like,” explained Rochelle Rogan, the librarian/media specialist at Dennis Intermediate School in Richmond, IN.

Lee Ann Coffey, the librarian at Alexander Elementary School in Houston, wrote, “I am not able to acquire new releases, replace lost items from the spring when we suddenly went virtual, or continue my efforts to develop an equitable collection.”

The majority of school libraries are staffed with a full-time librarian/media specialist, according to the survey. Eighty-four percent are staffed with a full-time librarian/media specialist, down only one percent since 2017. Those without a full-time librarian are more likely to have one who is part-time.

When it comes to who makes budget decisions, in half of schools surveyed, the principal sets the budget. In 34 percent of schools, the school board is involved. Almost all respondents, 95 percent, said they have influence on purchases for the school’s LMC.

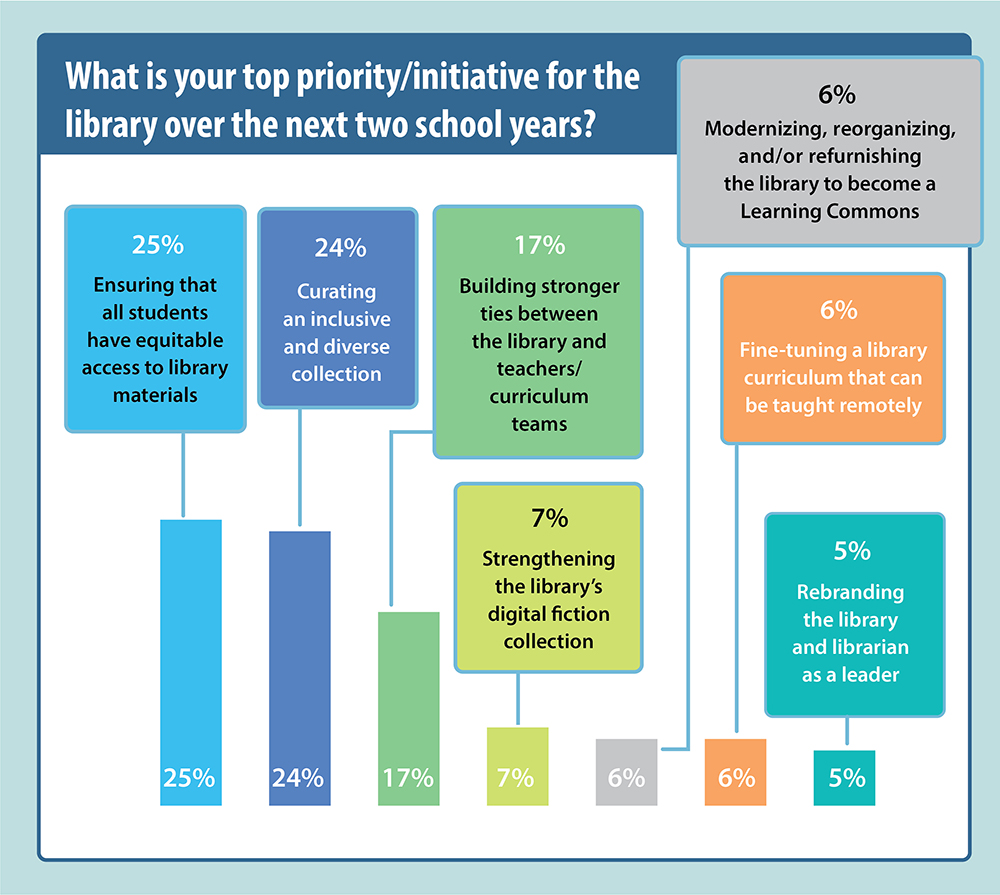

Looking ahead, librarians wrote that their priorities for the next two years are to ensure that all students have equitable access to library materials; to curate an inclusive and diverse collection; and to build stronger ties between the library and teachers/curriculum teams.

In the meantime, librarians are making the most of what they have at the moment. Alisa Mills, librarian at Martinsburg (WV) North Middle School, wrote, “The budget is tight, but fairly manageable. It would be nice to have enough to do everything the library truly needs.”

# # #

About the Survey: The survey link was emailed in mid-November to approximately 21,000 school librarians. The survey closed in early December with 901 responses. The results were weighted by type of library (elementary, middle, high and K–12) and by U.S. region.

Melanie Kletter is a teacher and freelance writer in New York City.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!