How Sheltering in Place Shows Us a More Accessible World

Employees with disabilities and chronic illnesses have long fought for basic accommodations now granted to millions of workers from home. Here's what else is needed.

|

Ace Ratcliff |

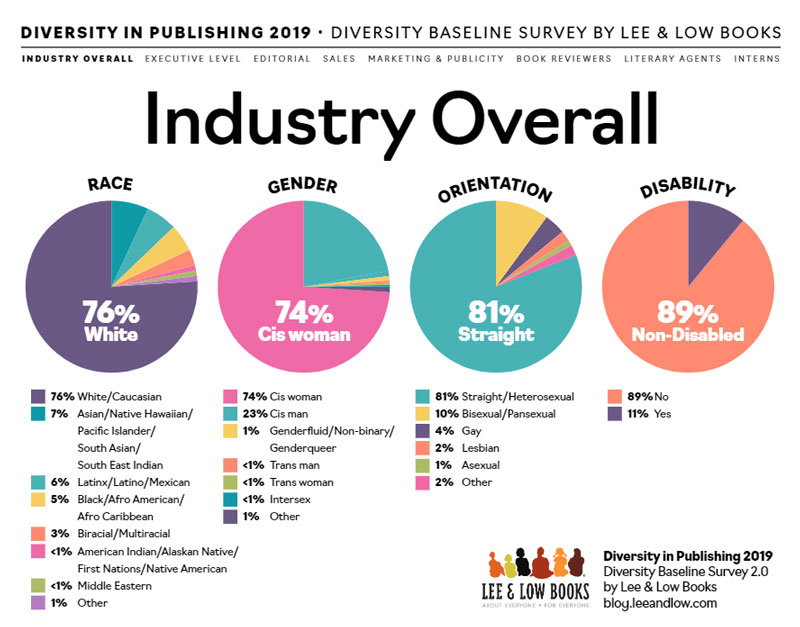

In 2015, Lee & Low released its first Diversity Baseline Survey (DBS), establishing concrete statistics about the diversity of the publishing workforce by quantifying the racial, gender, sexual orientation, and ability makeup of the publishing industry’s employees. Producing the DBS has helped deepen Lee & Low’s knowledge about the varied aspects of diversity, while also revealing aspects of personal identity that are not as familiar to our lived experiences—areas that require us to listen and learn more. The latest iteration of the survey, DBS 2.0, which was made public at the beginning of 2020, was no exception.

Typically, after we drop the survey, we start to dissect specific parts of the data. With a publishing workforce reporting as 89% non-disabled, numbers like these indicate an acute lack of representation when it comes to people with disabilities. In order to learn more about the disability numbers included in the survey, I interviewed writer and disability rights consultant Ace Ratcliff, who vetted the choices for the disability question in DBS 2.0.

Some of the issues that Ace raised were completely new to me. Although I may know a thing or two about diversity when it comes to ethnicity, the kind of accessibility issues that people with disabilities face every day are ones that so many of us are becoming familiar with in our COVID-19–limited world. Below, we talk about the survey results, what the results reveal about people with disabilities in publishing, and the realities of a world that is often not as accessible as it should be.

In times like these, when shelter-in-place orders have been enacted, do these restrictions present new obstacles that people with disabilities have to circumvent?

It’s a big question that lots of disabled people are discussing right now. On one hand, we have absolutely lost access to much of our regular, maintenance-type medical care; on the other, many of the things the disabled community has been asking for from the world at large are becoming reality as we shift into sheltering in place. For example, telecommuting is now the way to work; I can’t even begin to tell you how many of us have been told we have to be at work in person in order to have a job. (Hard to do if the building is wheelchair inaccessible!) Another small example is seeing new releases come to video on demand. When movie theaters are not accessible to wheelchair users, when closed captions devices don’t work, when there aren’t open caption showings of movies, we don’t have the opportunity to see new releases—but now they’re suddenly in our living rooms. So, I think the bigger question is: If and when the world returns to some sense of normalcy, how much of this newly found accessibility will stick around?

|

|

|

The Diversity Baseline Survey (DBS 2.0) was created by Lee & Low Books with co-authors Laura M. Jiménez, PhD Boston University Wheelock College of Education & Human Development; and Betsy Beckert, graduate student, language and literacy, Wheelock College of Education & Human Development |

What do the disability numbers tell us about the staffs that work in publishing?

AR: It’s pretty clear from looking at the results of the DBS that publishing is extremely exclusive and likely remarkably inaccessible, given that the majority of those who took the survey identify as nondisabled. The fact that this extends across all departments, from sales to executive levels, is unsurprising but remarkably frustrating.

Would these numbers encourage or discourage people with disabilities to pursue a career in publishing?

It’s likely that the numbers would discourage disabled people; it’s hard to imagine yourself in a role if you don’t have anyone else that has a disability (physical or otherwise) in a similar position. Hopefully, though, it also encourages disabled people to try to be more involved, because it’s very obvious that diversity is desperately needed across all types of minority groups. It becomes especially important to be included, especially when it comes to disabled people. Since disability can!

How would the industry need to change in order to make jobs in publishing more accessible?

There are a lot of things that can be done to ensure accessibility. First and foremost, the buildings where publishing houses work need to be accessible to disabled people—and disabled people, especially those who use accessibility devices like wheelchairs, need to be involved in vetting said buildings. There also needs to be opportunities for teleworking at all levels, including at the executive levels. Events with public speakers need to include sign language interpreters. Video that is sent around needs to include closed captions. There need to be opportunities for people to attend medical appointments or take a mental health day without punishment. Perhaps most importantly, disabled people need to be involved in setting the accessibility standards for their publishing house, and these standards need to be reviewed and updated on a regular basis. Additionally, having cross-communication between publishing houses across the industry will be important for making sure that these standards are maintained and updated regularly.

I recall that when we were vetting the survey question choices, I had asked if there were other disability advocates like yourself who would want to lend their expertise by name to the survey and you said there were not—that people were afraid to go on record. Do you see this as a problem?

I think the fact that disability justice advocates don’t want to be named is a problem, but the negative reflection is not on them. The fact that people don’t want to be named in conjunction with the results from this survey says a lot about publishing as a whole, and it’s not a particularly positive story. Unfortunately, until publishing—and the world—exist in a way where disabled people are not just included but part of calling the shots, that’s going to continue to be a problem.

What you are trying to achieve in your own activism as a disability advocate?

I think the best phrase I can use to describe what I want to accomplish as a disability advocate is disability justice. Ultimately, I believe that [singer and political activist] Nomy Lamm said it best in this essay, “The Body is Not an Apology,” which is worth a read. As Lamm says, disability is a cross-section of every group of society, regardless of race, gender, age, or orientation. As such, every movement has to advance disability justice and vice versa. Disability justice examines disability and ableism as it relates to other forms of oppression and identity, and was originally conceived by the Disability Justice Collective, a group of black, brown, queer, and trans people. My work as an activist is about ensuring that the disability justice movement becomes the focus for discussions about inclusion.

|

Jason Low |

Do you want to end with a call to action to support your cause? I feel that diversity as it connects to disability and access or lack thereof should be something folks continue to keep learning about.

The most important thing nondisabled people can do right now is follow disabled people on social media, to see how they can throw their support behind causes that will continue providing accessibility even after COVID-19. A great place to start is the Disability Visibility Project, which is run by the incredible Alice Wong (who is amazing about amplifying the voice and works of many other disabled people).

Jason Low | he/him | is the publisher and co-owner of Lee & Low Books, the largest multicultural children's book publisher in the United States. Lee & Low is proud to publish books about everyone and for everyone. leeandlow.com

|

Ace Tilton Ratcliff | they/them | lives and works in sunny south Florida, surrounded by a pack of wild beasts. They’ve worked as a mortician but made the move to freelance writer, artist, and disability consultant at Stay Weird, Be Kind Studios in 2017. They have written for Huffington Post, io9, PopSci, Fireside Fiction, and more. Their meatcage struggles with hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, dysautonomia, endometriosis, and other comorbidities. Twitter: @mortuaryreport |

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!