Speaking Up and Acting Out with Celia C. Pérez

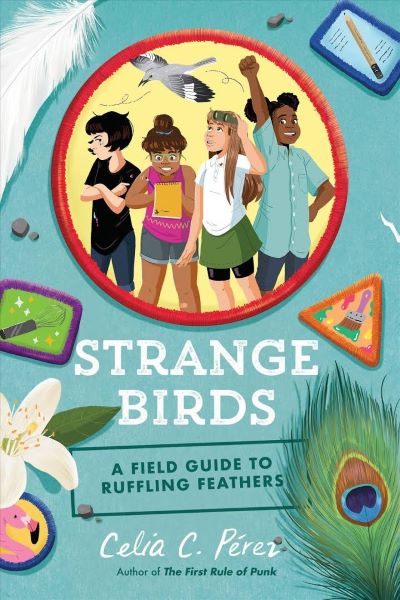

Award-winning author Celia C. Pérez (The First Rule of Punk) spoke with SLJ about tactile story writing, activism, and living vicariously through one's characters in Strange Birds: A Field Guide To Ruffling Feathers.

|

Photo by Celia C. Pérez |

When 12-year-old Lane DiSanti drops super-secret club invites into the kids' book club bags at the library, she doesn't know what to expect—she just knows that she's lonely in her grandmother's South Florida mansion. She certainly doesn't expect to find herself on a (somewhat) risky mission with new club members Cat, Ofelia, and Aster to protest the Floras scout troop and their use of bird feathers in their beloved pageant hat. But as their friendship develops and the stakes get higher, the girls learn that sometimes shaking things up is the only way to make a change. Award-winning author Celia C. Pérez (The First Rule of Punk) spoke with SLJ about tactile story writing, activism, and living vicariously through one's characters in Strange Birds: A Field Guide To Ruffling Feathers (Kokila, Sept. 2019).

In your novel, Ofelia, Aster, Cat, and Lane, calling themselves the 'Ostentation of Others and Outsiders,' bond over protesting the unethical use of bird feathers in a Floras scout troop tradition. Why did you choose this cause to bring the group together?

If I remember correctly, this part happened organically as I was doing research. A lot of the story is about challenging and questioning history and traditions. Cat's character wants out of the Floras who are not only a tradition in the town, but also a tradition for her family. Somewhere in the research process, I learned about the history of bird hunting in the late 19th and early 20th century. Birds were hunted—some species to the brink of extinction—for their feathers, which were all the fashion rage. These were often used to decorate hats. Sometimes bird parts and even entire birds were used. This became part of Cat's story.

When the girls first meet, they don't instantly click. They're from different backgrounds but they're all lonely kids looking for friendship and adventure and independence. The event that brings them together revolves around Cat and the Floras. Initially, the other girls aren't necessarily invested in the hat, but they want to help someone who could be a friend. As that friendship develops, they become invested in what protesting the hat means. The hat brings them together, but it's really more about what the hat represents for the girls.

The group’s slightly awkward dynamic as the girls get to know each other feels spot-on; they aren’t immediate best friends, but build up trust with each other gradually. Did you draw from real-life inspiration for this authentic depiction of new friendships?

I think I drew from my own experiences as someone who identifies as an introvert and who doesn't always easily warm up to people. I'm not embarrassed to admit that I live in my own head a lot, and I'm sure that makes me awkward at times. I don't think the awkwardness of meeting people for the first time and making friends goes away just because you're an adult.

All four girls have unique interests and skills that they bring to the team: Lane contributes through her artistic endeavors, Aster brings baked goods, Ofelia uses her keen reporter’s eye, and Cat’s passion for birds sets their mission in motion. How did you develop each girl’s background and balance their individual journeys within the broader plot?

While Sabal Palms is a fictional town, I based a lot of it on Coconut Grove, an area that's a little south of Miami, FL, as well as on the neighborhood I grew up in, a part of the city called Allapattah. South Florida is rich with cultures from everywhere because it's a place where people from all over the world, my parents included, have gone to make a new life. I knew I wanted the girls to reflect the kinds of friends I had growing up—kids from varied backgrounds—and to reflect some of the socioeconomic disparity you can see in large cities. Having four main characters was fun because it allowed me to give each one her own interests and skills, which were things I was interested in or curious about.

Balancing their stories was definitely a challenge. At times I felt like the cat in those gifs where the poor creature is tangled in a ball of yarn! I think the decision to devote each chapter to a different girl was helpful because it allowed their individual stories to be told while also telling the story of the group. The earliest version of the book only included Ofelia and Lane and was going to be told from Ofelia's viewpoint. When Cat and Aster came along, it felt important to let each girl have a story, especially because they were all coming from such different backgrounds. I wanted to give each one the opportunity to tell their collective story from her own experience. I mapped out each girl's arc as it connected to the story arc of the group.

You touch on gentrification and class as Aster’s grandfather teaches her about the “wall” that essentially divides the town by race and socioeconomic status. Why was this concept important to include in this story?

When I first had the idea for the book, I knew I wanted it to be set where I grew up in South Florida. I thought of the location as its own character with its own story. And that story, like the story of many places in this country, involves segregation and gentrification. I grew up in a pretty segregated neighborhood that was exclusively immigrants from Latin America and the Caribbean; the schools I attended were almost exclusively Latino and Black. Many years later, those areas are changing through gentrification. While the town's division isn't the main focus of the plot, it's something that is always present because it is part of why these girls are strangers to each other at the beginning. They live in the same town, but in different worlds. Most, maybe even all cities have this kind of divide where some residents don't often cross into each other’s neighborhoods. It's easy to assume that this is just the way things are and ignore the history that makes places so divided. I thought it was important to acknowledge these different experiences. As their friendship develops, each girl's awareness of how her family history is intertwined with that of the others, and of the town, grows as well.

What did your writing process look like for this offbeat ensemble adventure?

What did your writing process look like for this offbeat ensemble adventure?

My writing process always requires stepping away from the computer. It tends to be visual and tactile. I do a lot of color-coding and manually laying out and manipulating what I'm working on before making changes on the electronic document. I cut scenes out with scissors and tape them where I want to move them. I think I have to be able to see the whole thing and move it around with my hands in order for it to make sense in my brain. I don't know if that's a product of zine-making which, for me, has always meant physically laying out pages, or if it's part of what attracted me to zines in the first place. For Strange Birds, the writing process also meant creating a timeline for the history of the town and a map of the immediate areas in which the story takes place. I think having this writing process helped with the challenge of writing an ensemble. It makes it easier to see each girl's story within the larger story.

How did you “ruffle feathers” as a kid?

It's funny because readers will often ask if I was a punk as a kid, like Malú from The First Rule of Punk. I hate to burst their bubble but at 12, I was neither a punk nor a feather ruffler. I was a quiet, shy kid who lived inside books. My parents strongly discouraged us from getting into any kind of trouble, and I lived in fear of disappointing them. I think that's why I write characters who get into shenanigans and speak up and act out. Twelve-year-old me lives vicariously through them.

In your author’s note, you write: “Change may not always come quickly, but making our communities and our world better is always worth the work.” Why did now feel like a good time to write a book centering tween activism?

I don't think there's ever a bad time to encourage young people to care about and become involved in their communities. Of course, we're living in especially troubling times. It feels like something has to give sooner than later. I love writing and reading middle grade. The more I think about it and the more I interact with kids who fall into that range—my publisher notes it as 9-12, but I would even go a little younger and a little older—the more I believe that this is the perfect age group in which to instill and to foster all the good things we want for the future of our world. They're old enough to understand and to be outraged. They're young enough to still genuinely believe that change is possible. They're curious and engaged and open-minded. Not to generalize, and obviously, I'm not a child development expert, but I would argue that they are more so those things than people at any other age. I think teaching kids about activism and about different ways to be activists empowers them too. There are a lot of societal forces that make people, especially children, feel powerless.

What do you want readers to walk away with after reading Strange Birds?

I don't start out writing with a set path or outcome for the story in mind. I'm not much of an outliner, and I like to see what comes out of each character's world as I'm developing it. So I don't really have an intentional outcome or takeaway, and even when I am at a point where a story has direction, forcing it to fit an outcome can feel unnatural. In the same vein, I'm trying not to tell people what I hope they get from the book. I always love to hear what individuals take from a story. I think we take what we need from books, and that's different for everyone. My hope is that anyone who reads Strange Birds walks away with something they needed.

Strange Birds: A Field Guide To Ruffling Feathers will be published September 3, 2019, from Kokila.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!