Minnesota School Librarians Supporting Students and Peers

As ICE raids continue in the Twin Cities, school librarians are stepping up for students, staff, and their communities.

As ICE raids continue in Minneapolis and St. Paul, MN (MSP), the school day is anything but normal. Parents are standing guard and acting as escorts for immigrants and all nonwhite students at drop-off and pickup, recess has often been moved inside while ICE agents stand just outside campuses, schools are facilitating online learning to accommodate children whose families are too scared to let them leave the house, and students are staging walkouts in protest. Every aspect of life in the Twin Cities has been impacted, according to those who live there.

In the middle of it all, school librarians are doing what school librarians do: creating and sharing booklists to help process emotions and understand history, teaching media literacy skills to combat rumors, sharing resources, distributing and maintaining electronic devices, and supporting each other personally and professionally.

“I would like to be doing more to support people, but my job is pretty all-encompassing in my life,” a school librarian from the MSP area said. “I’ve been trying to reassure myself with reminders that being a school librarian—connecting kids with diverse stories, helping them build their literacy and critical thinking skills, giving them the tools to see through spin and propaganda—is its own kind of activism. I am giving it everything I have.”

“I would like to be doing more to support people, but my job is pretty all-encompassing in my life,” a school librarian from the MSP area said. “I’ve been trying to reassure myself with reminders that being a school librarian—connecting kids with diverse stories, helping them build their literacy and critical thinking skills, giving them the tools to see through spin and propaganda—is its own kind of activism. I am giving it everything I have.”

SLJ was in contact with multiple librarians who wanted to talk—saying they felt not only a catharsis in sharing what they were going through but a need to let people outside of the area know what was happening—but in the end, many changed their mind about speaking because they were afraid. Even offered anonymity, they, and in some cases their administration, feared that what they said would give enough clues to identify immigrant students in their school or reveal security measures the district is taking. They were fearful that speaking to SLJ about how they were supporting students and one another would lead ICE to their doors—of their schools and their homes.

Inside school buildings, educators are trying to keep things as routine as possible.

“School is a place that needs to be safe and stable,” said a school librarian from a Minneapolis suburb—an outer ring, as they are called in the area. ICE has not been on her campus but has been in the community, albeit not as widespread as in Minneapolis. “We were given the instructions [to] try and maintain regular classroom activities as much as possible.”

Of course, ICE activities and the latest news remain a dominant part of conversations.

“Students ask questions, definitely,” she says. “You answer to the best of your ability, [but] don’t let it dominate a whole class period. You don’t know what somebody else is going through, where that might trigger something. Just like in any other crisis, if they need counseling support, we get them to the counseling office. We have students that are not coming to school if they don’t feel safe. We have students that are coming to school, because this is a place that they feel safe.”

Even in an area where ICE interactions might not be daily occurrences on neighborhood streets or in local stores, the impact is significant and disruptive.

“Everybody’s scared, everybody’s nervous,” said the librarian. “The teachers are scared for our kids of color. Our staff of color are carrying all their papers just in case.”

Carrying their papers in case they are stopped in the street and forced to prove their citizenship because of the color of their skin —in the United States of America.

“Never did I think that would be something that I would ever have to say,” she added. “I’m frustrated. I’m angry. I’m sad—in disbelief and just so angry that our staff and our students are going through this.”

Her focus is on making sure “that we’re being fierce advocates for our staff and for our students.”

In an attempt to continue educating those too afraid to come to school, districts are implementing online learning and hybrid learning on the fly. For people who think that should be easy because the schools went online for COVID in 2020, it is not.

“It’s a very different situation,” said a school librarian.

In Minnesota, when COVID hit, Gov. Tim Walz closed schools for two weeks to give administrators and staff time to plan and develop protocols and procedures. This time, Minneapolis Public Schools decided to allow students to learn online, announcing it over a weekend and beginning it that Monday.

“In Minneapolis, pretty much all the librarians are canceling any sort of scheduled classes, because they’re getting devices, they’re getting hot spots, they’re doing password resets,” she said.

Many of these families haven’t gone through online learning before, she noted. They don’t know how to join a Google Meet or Zoom, according to the librarian, and instructions must be in English, Spanish, and various other languages to meet the needs of the diverse school communities.

“It’s mass craziness,” she said, adding that librarians are just in “survival mode.”

The St. Paul Public Schools closed on Tuesday, January 20, and Wednesday, January 21, for teachers to prepare to begin virtual learning in that district.

School librarians in the area are leaning on one another, but supportive words from outside the area would be appreciated, as well.

‘Please write, please send letters of encouragement and support,” one Minnesota librarian said. “Write not just to schools but to all of Minnesota. Locate an address and write.”

The Information and Technology Educators of Minnesota, the school library division of the Minnesota Library Association, sent an email to the organization’s listserv of Minnesota school librarians, library workers, retired librarians, and community library advocates.

The email, which was shared with SLJ, began by thanking people for reaching out and offering support and resources to the Minneapolis Public Schools. It shared two "crisis and trauma" booklists, one for elementary students and another for secondary students, with titles to help kids process the situation. It also included ways those outside of the Twin Cities could support affected families and communities, including donating to a local food pantry, assisting an organization that is sending kids free books, patronizing MSP BIPOC-owned and immigrant-owned businesses, and calling legislators.

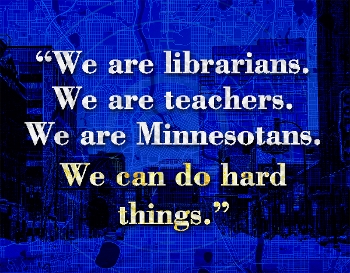

The email concluded: “We are librarians. We are teachers. We are Minnesotans. We can do hard things. In the wise words of Teddy Roosevelt, ‘Do what you can, with what you have, where you are.’

“Sending hugs, tissues, and chocolate!”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!