How Native Writers Talk Story: Honoring Authentic Voices in Books for Young People

As more Native writers make inroads into childrens' publishing, educators and readers must set aside internalized misconceptions about Native life, people, and nations.

We are the first storytellers on this continent. But despite the increasing visibility of Native and First Nations today, many readers are still new to our ways of making sense of the world through literature.

Our stories often feature distinct, Indigenous literary styles and cultural references. Joyfully, the community of Native and First Nations writers creating books for children and teens keeps growing. With each publication season, an ever-expanding body of Indigenous youth literature is available.

Meanwhile, as more Native writers make inroads into publishing for children and teens, it is imperative that non-Native adult readers work to see the heart of these stories—and recognize and set aside their internalized misconceptions about Native life, people, and nations. Getting books by our authors into the hands of Native kids—one of their primary audiences—and non-Native kids is important. But equally so is the gatekeepers’ commitment to examine how they experience and understand our ways of storytelling.

How can readers mindfully enter this conversation? What should they take into consideration while moving forward?

Native writing styles

To start, the literary devices reflecting Native values, customs, oral traditions, linguistic patterns, and day-to-day sensibilities must be respected as such. On the page, some of these stylistic choices may seem disconcerting to those unfamiliar with them. But young readers benefit from exposure to writing informed by lived experience and Indigenous worldviews.

We all grew up reading books written primarily by non-Native authors for non-Native kids, like Bridge to Terabithia by Katherine Paterson and Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret by Judy Blume. We understand their shape and substance, and modern Indigenous writers often embrace a hybrid literary approach. But we must raise up our own literary traditions, too. We must advocate for them in a society where Native and First Nations people have been pressured—at times through force, legislation, and oppressive U.S. and Canadian governmental boarding and residential schools—to abandon our cultures, including our myriad approaches to the literary arts.

On the page, that may translate into a heightened emphasis on daily life, on the desire line of a community (rather than of an individual), on an absence of connective tissue in nonlinear narratives, on an everyday personification of the natural world, or on a seamless integration of traditional characters, among infinite other possibilities springing from hundreds of different cultures and languages.

On a related note, Native fiction writers’ decisions to incorporate or leave out cultural details, references to Indigenous language(s), and historical context reflect artistic perspectives and specific stories’ needs. Non-Native educators and literary experts may long for narrative framing more within their comfort zones. But ultimately, this cheats Native and non-Native kids.

A Native-centered process facilitates an authentic Indigenous worldview. It can also lead to confusion, especially among non-Native adult readers who have minimal experience with these texts, Native Nations, or citizens. Rather than dilute our authenticity, we ask for nuanced reflection on Native writing to build appreciation.

[READ: Native Perspectives: Books by, for, and about Indigenous People | Great Books]

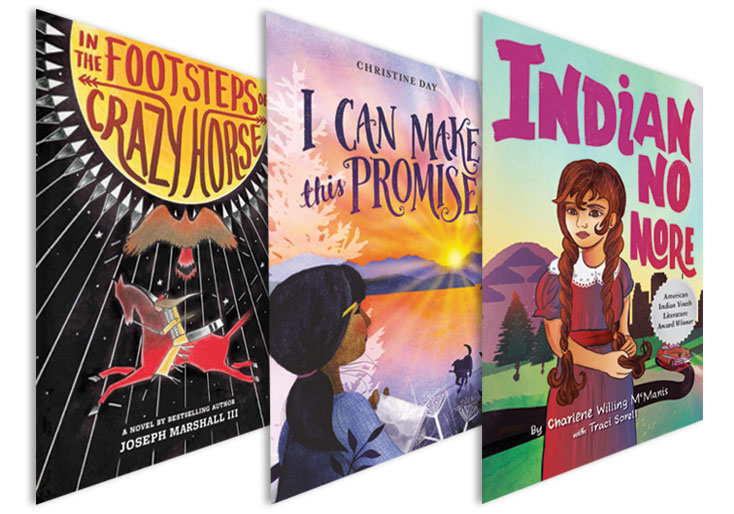

Today’s Native and First Nations books offer multiple opportunities for study. An Indigenous writer, for example, may have a first-person Native protagonist offer a bit of illuminating cultural commentary. In Christine Day’s I Can Make This Promise, a middle grade novel about the ripple effects of a baby’s adoption away from her Native family and tribal community, protagonist Edie and her mom discuss federally recognized tribes of the Pacific Northwest and the treaties they signed.

Or, a character may make only a passing mention of a cultural reference that doesn’t readily translate to non-Native readers. Charlene Willing McManis deftly accomplishes this by coupling Native humor with a reference to Sasquatch in Indian No More, a poignant middle grade novel that shines a light on tribal termination and relocation in the 1950s.

In such cases, the writer’s choice about what to convey and how to do so may depend on the protagonist’s voice, character, mood, internal and external arcs, or backstory. Likewise, a Native fiction writer’s choice to expand on topics is a matter of discretion. Some authors maintain that a story should stand on its own. Others prefer to speak from the heart through themes. Virtually all will remain silent about cultural subtexts that aren’t typically discussed in mixed company. And the degree of factual disclosure from nonfiction to fiction will vary dramatically.

Young readers

It is abundantly othering for Native kids to read stories in which characters who are supposed to reflect them are nothing more than info-dumping paper dolls. It sends the message that books may be about them—or about an outsider’s vision of them—but are never for them in a deeply meaningful way.

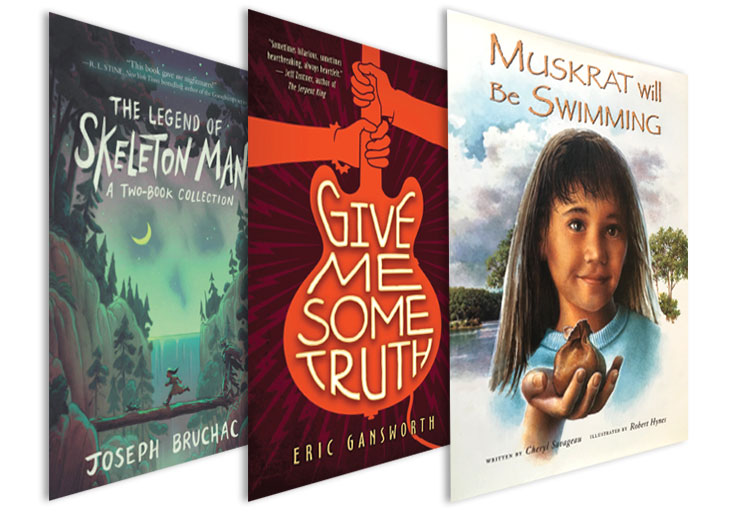

In contrast, consider how, in his middle grade novel In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse, Joseph Marshall III uses Grandpa Nyles’s stories about Crazy Horse while on a road trip with his bullied grandson to interweave the historical and the contemporary. Likewise, Cheryl Savageau’s picture book Muskrat Will Be Swimming employs an intergenerational relationship very familiar to Native readers to deliver a similar message to younger children about remembering the strength of their culture amid the taunts of schoolmates.

Think of tree ring patterns. The kids who are most directly mirrored by a protagonist should be centered by the writer in terms of the target audience. It’s what makes the most sense in terms of character agency, desire line, voice, world building, humor, and every other element of story.

An adventure driven by, say, a 12-year-old contemporary Cherokee boy should reflect a culturally compatible literary approach. This includes the context, the voices of the narrator and secondary characters, the central theme, and the shape of the story. Some Native books may offer additional layers of nuance appreciated by only certain Native readers. That’s OK, as long as the story is still cohesive, resonant, and accessible to other kids, too. Still, not every young reader needs to “get” every joke for a Native story to be funny to everyone.

That said, Native fictional stories aren’t educational texts, and their quality shouldn’t be based on how much content informs non-Native readers. Put another way: They’re not better if the Native experiences are bulked up to serve a curriculum—or thinned out so cultural content is served in bite-size chunks. Rather, that level of content should be driven by what serves story and the author’s sensibility.

Natives (re)claiming our space

The world is saturated with misconceptions about First/Native Nations and peoples, so any stories by Native creators about Native characters tend to offer positive educational benefit. Simply sending the message that we exist as human beings—not boogeymen on the prairie or supernatural creatures or feather-dripping Yodas—is an improvement.

We come from hundreds of distinct tribal cultures and intersecting identities with our own storytelling traditions. Today, we’re successfully working within hybrid forms, alternative formats, and speculative fiction, paying tribute to the voices and visions of our communities, and nodding to mainstream influences.

[READ: Strategies for Teaching Seven Native-Centered Books to K-12 Students]

Consider the way Eric Gansworth blends his stunning visual art, love of the Beatles, and excellent wordsmithing in his young adult novel Give Me Some Truth to make us feel as if we’re right there on the Tuscarora reservation with his characters in 1980. Or, turning to fantastical fiction, in “The Legend of Skeleton Man” collection, Joseph Bruchac centers the traditional agency of Native women through his protagonist Molly in two modern, entertaining middle grade horror stories. It doesn’t matter that most readers won’t immediately—or perhaps ever—absorb all the subtleties in these works. With commitment, patience, and time, we’ll all come to better understand one another.

For those new to the Native literary conversation, we give the same advice we offer to beginning writers. Read. Broadly. Extensively. Frequently. Read a wide array of Native voices. Realize that while patterns will emerge, individual approaches vary. They may conflict and evolve. Err on the side of questions. Become comfortable with discomfort. Recognize gaps within your global expertise. Earn knowledge and insight through sustained effort.

Blessedly, it’s easier for young readers to navigate these dynamics. They don’t have to unlearn as much. They’re more open to the unfamiliar. Their expectations are fluid.

Whether Native or not, young people read fiction for story. What’s important is that we hold their attention and engage their hearts. What matters is that, through an authentic artistic experience, they connect with a narrative that makes them care enough to keep turning pages.

Cynthia Leitich Smith is a Muscogee Creek Nation citizen and award-winning children’s and YA writer. Traci Sorell is a Cherokee Nation citizen and author of award-winning poems, fiction, and nonfiction for young people.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!