Getting Creative with Summer Reading Programs

Across the country, school and public librarians are creating their own summer reading programs that not only combat the academic slide and keep kids reading but promote book choice and personal connection.

|

Illustration above and SLJ February cover below by Kathleen Fu |

Every other week last summer, a group of students voluntarily showed up to Leesville Road Middle School in Raleigh, NC, books in hand.

“It filled my bucket,” says Leesville school library media coordinator Evelyn Bussell, who met the students in the library to talk about what they were reading. “[It] made my heart happy to see them get excited.”

The kids were excited both about the books and to see each other. And Bussell was more than happy to take the time from her summer break to meet and talk with them, facilitating those relationships through reading.

“It was a way that they could connect with students who are like them,” says Bussell. “Some kids have lots of friendships. Some kids, they just are kind of on their own. A lot of times, at least in middle school, I see them making friendships with people who have the same electives or play the same sports, but not so much kids who like to read. So it was a great opportunity for kids who are into reading to expand their circle of friends.”

Summer reading can be more than recording reading times to collect prizes at the local library branch or a few mandated titles from a high school English class. The Collaborative Summer Reading Program creates resources and programming for public libraries around a new theme each year. (This year is Unearth a Story: Desentierra una Historia—Dinosaurs/Archaeology/Paleontology.) But across the country, school and public librarians are creating their own summer reading programs that not only combat the academic slide and keep kids reading but promote book choice, personal connection, and even outdoor activities.

|

Readers note their reaction with emoji Post-its.Tri-North Middle School, Bloomington, IN |

Denver Public Library (DPL) runs the Summer of Adventure, which gives young patrons at 29 branches the opportunity to engage in reading, making, and exploring activities, all with a focus on literacy. At the end of the summer, participants get a ticket to an end-of program party at the Denver Zoo.

“Summer of Adventure strives to connect youth with books, literacy, and their own learning,” says Rachel Robinson, family engagement program administrator at DPL. Robinson oversees the summer reading program and is still working out the details for this year. As in the past, she hopes to not only get the city’s kids reading, but help them build a home library.

Free books are given out at author visits, book celebrations, kickoff parties, and special events throughout the summer. Last summer, DPL gave away nearly 5,000 free books to Denver youth. To help generate interest in titles and more checkouts throughout the summer and beyond, the DPL collection is highlighted at events, on book displays inside branches, at story times, and virtually on its YouTube channel.

The program includes book recommendation lists for kids and teens, and an educator toolkit for classroom teachers who want to use the program during the last weeks of school or during summer school programs.

Summer reading programs are the most common way that schools collaborate with public libraries, with school librarians promoting the public library list and programming. At Flower Hill Elementary School in Gaithersburg, MD, school library media specialist Melissa King does joint programming throughout the school year with her local public library branch. Toward the end of the school year, the public librarian presents their branch’s summer reading challenge to students. During the summer, King hosts one or two school library events that include read-alouds and related STEAM activities. She is planning now for the coming summer and considering adding some more read-alouds in July and early August. She would like to focus on nature-based books as she finishes work on her environmental educator certification.

|

Whittaker makes care packages for participants in her summer reading program.Tri-North Middle School, Bloomington, IN |

All year long

When it comes to summer reading programming, it’s never too early to start planning.

Meg Whittaker attended a session at the American Library Association (ALA) Annual conference in June 2018 that kickstarted her summer reading program the following year.

“Recreate your summer reading program by leveraging the enthusiasm of avid readers in your community to infect the less-avid with the magical combination of a compelling book and a personal connection,” the session description read.

The presenter mentioned that the program required each student be given a copy of the book for the summer, and Whittaker remembers attendees walking out because they didn’t think it was feasible for them. But she stayed and listened. She knew she could tweak it to fit her school community and had enough time to figure out how. When she learned that the program involved faculty reading the books and facilitating discussion with students at the start of the next school year, she was sold.

“One of the things I loved about the program that really stuck with me from that initial ALA presentation was teachers talking the talk and walking the walk,” says Whittaker, middle school library media specialist at Tri-North Middle School, a school for seventh and eighth graders in Bloomington, IN. “We’re doing it too.”

As Annual took place early in summer break, she had a year before she would have to start. With that time, she could figure out what would work and what needed to be adjusted, write a grant proposal, and take the idea to her principal.

With approval, she launched the program in 2019 and has been doing it ever since, including two years online during the height of the COVID pandemic. She continues to adapt it. For example, the program presented in that ALA session had teachers suggest the books, which Whittaker did the first year. But, she found, teachers were looking for her insight and recommendations and preferred she suggest titles.

This is a program that is consistently in the back of her mind. She spends the year curating a list of 12 to 20 high-interest titles.

“I’m always looking for books and ideas,” she says, noting that when she reads something she feels would have an impact on her young readers, she adds it to her list, which also includes titles from a state list the school uses throughout the year.

Originally she thought she always needed to include a classic, but realized that wasn’t necessary. Last year, however, a student told her they had always wanted to read Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury but never had time, so Whittaker added it to the summer list. There are always middle grade and YA choices and at least one graphic novel. The only constants are Red Queen by Victoria Aveyard and The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins. Whittaker calls them the “welcome to middle school” books that are always popular and alternates them each year, with one or the other always appearing on the list.

Students have input, too. In February, she’ll do a blind date with books, putting out about 50 titles for seventh graders to read and let her know what they thought. The ones kids like the most will end up on the list.

When she does elementary school visits in April with sixth graders, she mentions summer reading. In May, she goes over the list with teachers and then lays out the books for rising eighth graders to choose from. Seeing the covers, finding out what their friends are reading, and being able to pick up the books and look at them all impact their choices. Whittaker also hangs posters by the classroom doors of participating faculty and staff to let kids know which adult is reading what. She is particularly proud that adult participants are not just English teachers. She has science and math teachers, administrators, and counselors (who often handle the books with more difficult subject matter).

Whittaker tries to finalize the list by mid-March at the latest, so she can share it with her principal and the local public library branch. That way they know there will be extra demand for those titles and have the materials ready in print, audio, and ebook versions as much as possible. She also shares the list with local bookstores, so they are prepared. There is often a discount for students in the summer reading program, she says.

Those participating receive a care package with snacks and emoji Post-its they can use to mark pages with their reactions. They can check out a copy of the book from the school library, get it from the public library, or obtain their own copy from a bookstore. To ensure there are enough books at school, Whittaker has used library funds, grant money, and funding from the PTO.

While Whittaker always wishes more students would participate, the program has been an undeniable success since it began. After a “big start” in 2019, it took a hit during COVID and continues to try to rebound. Right now about 15 percent of eighth graders participate and 10 percent of incoming seventh graders. Perhaps even more telling about the program’s value and impact is that Whittaker has had four different principals during that time, and after hearing about the program, each one has supported its continuation and even participated.

|

Students from Leesville Road Middle School in Raleigh, NC, read and reviewed new titles over the summer.Leesville Road Middle School, Raleigh, NC |

Student collaboration

Bussell’s program was more spur-of-the-moment. Having received 80 books from a DonorsChoose grant in late May last year, she knew she couldn‘t get them cataloged into the collection before the end of the school year. She also knew she didn’t want to spend her summer break reading all of them, and thought maybe some of her students would want to help. They could get early access to the titles and provide summaries and reviews.

Bussell reached out to English teachers to ask for their avid readers who might be willing to sacrifice some of summer break to talk books. Over the course of the break, a group of up to 12 came together every other week. By the end of the summer, with all the DonorsChoose books read, they were able to pick titles. The conversations allowed Bussell to get insight into her collection development as well.

“I was getting their feedback on what they liked about these books,” she says. “If they didn’t like them, why not?”

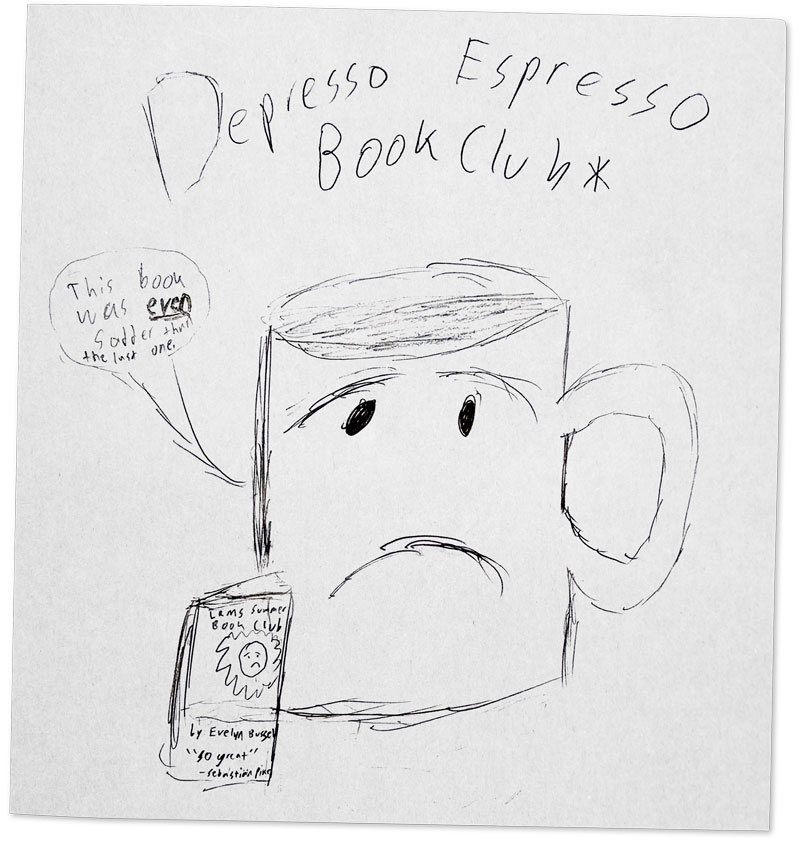

One student noted that all the new books seemed to be depressing or have a heavy theme—a fire, a death, a lost relative—jokingly naming their group the Depresso Espresso Book Club. Bussell hadn’t sought out that difficult subject matter, but in response, this year she requested “quick reads” for her Donor’s Choose grant.

The success of last summer’s pilot program has led Bussell to open it up to the entire school body this year. She is looking at her calendar to see if she can make the meetings weekly.

As for this year’s books, she has a smaller set coming from a new DonorsChoose grant and is expecting funding from the PTSA to buy new books, so she may form another summer book review club with new books. If she doesn’t have enough titles for that, she will allow students to each choose a book from the collection and then create a summer reading bingo card. She plans to start advertising the program before spring break and through April before meeting with interested students in May.

|

Book club drawing from a student in the Leesville Road Middle School summer reading program.Leesville Road Middle School, Raleigh, NC |

Keeping kids reading

These types of programs are particularly important in middle school, when the statistics show reading for fun continues to decline. According to Scholastic’s most recent Kids & Family Reading Report, those who read five to seven days a week drops from 46 percent in 6- to 8-year-olds to 15 percent when they reach high school. Reading for fun drops from 70 percent of 6- to 8-year-olds to 46 percent of 12- to 17-year-olds.

Social connections can be difficult in middle school, as well.

While Whittaker’s program doesn’t involve students and teachers coming together during summer break, the connection aspect is foundational. Kids are reading the same books as their friends or favorite teacher. They note their responses throughout with the emoji Post-its that Whittaker supplies. They read knowing the end of the program means getting together when school starts and talking about the book while sharing some snacks. It’s an instant early year connection and has led to more students signing up for the book clubs during the year.

Whittaker has read all the books, so in the instances where a teacher reading one title might change schools over the summer and not come back the next year, she takes on the discussion.

“We can make those connections and work together,” she says. “We’ve had fun, because I want them to convince others to read that book. We make it a fun, community building activity.”

The whole program is about reading for pleasure and connection, not logging minutes or taking notes.

“I want it to be a joy for them,” says Whittaker. “It’s all about the positive. We’re not testing. If [a student] only got halfway through the book, that’s okay.”

In one instance, only one student and one teacher had selected the same book, and the student hadn’t read it. Whittaker suggested the teacher start reading the book with him. He ended up continuing on his own and finishing the book.

“We just want our middle schoolers to keep reading,” she says.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!