An Emotional Night of Revelations from Caldecott, Newbery Award Winners

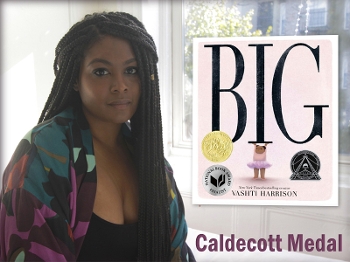

At the Newbery Caldecott Legacy Awards Banquet during ALA Annual, Caldecott winner Vashti Harrison and Newbery Medalist Dave Eggers shared previously unknown, very personal stories about the difficult events that led to the creation of their award-winning books.

The annual Newbery Caldecott Legacy Awards Banquet has a reputation for being a joyous and emotional celebration of children’s books and authors. This year was no different.

On Sunday night at ALA Annual in San Diego, Caldecott Medal winner Vashti Harrison took to the podium and left the audience inspired and in tears. Harrison began by speaking about the Black women illustrators who won Caldecott Honors before she made history by becoming the first Black woman to win the medal. Harrison then pivoted to something much more personal.

“I want to share my story with you in its messiest form, with all of the parts I usually leave out,” she said.  Harrison went on to document her journey as an artist and a person, and the impetus for Big, the picture book that earned the Caldecott.

Harrison went on to document her journey as an artist and a person, and the impetus for Big, the picture book that earned the Caldecott.

Harrison explained that she once drew only light-skinned, skinny characters. Her brain, she said, was hardwired to create these images reflecting those women she saw in magazines and Disney movies with bodies she aspired to have. As she became more conscious of the look of the characters she created, she said, “the world was changing.” She spoke of Trayvon Martin, Rekia Boyd, and Eric Garner.

Then Harrison continued:

“I heard that Black women had founded a social justice organization called Black Lives Matter, and I thought Black lives do matter. Black joy matters. Black stories matter. And Black art matters. I started to draw beautiful Black women, princesses and mermaids and fashion models. People online sent me so much love and support. They were hungry to see themselves in this art style, and I was so fulfilled by making illustrations that meant something to me and to others. But every time I drew another impossibly thin woman, I fed a self-hatred boiling inside. So I pushed myself to draw curvy bodies, fat bodies with dark skin—a correction, a confrontation, a subtle form of exposure therapy maybe. But these women were still conventionally beautiful and had curves in all the right places. Eventually, I had an intervention with myself, this hybrid fixation on my body, bodies that I draw, and what is good and what is bad was not healthy.

By this time, I was firmly established as a children's illustrator, but drawing had become impossible as I dealt with creative block and paralysis. To the outside world, I called this burnout from too many books too fast. Inside, I was agonizing over every drawing, every choice being political. Hair is political. Skin color is political. Bodies are political. I resolved to only draw children—children who are allowed to be chubby and chunky and thick, and we love them for it. Children, who have no wrong or incorrect curves or folds. Children for whom ‘big’ is good.

Drawing is such an intimate practice. You spend time with characters. You make decisions that seem microscopic but can change a character entirely—the placement of their eyes, the length of their neck. As I made these tiny creative choices, I wondered, at what age does big start being bad? For me, it was in the second grade when a girl looked over at my round belly and asked me if I was pregnant. That version of me is still inside and still hurting. I needed to make something to heal myself, and I needed to confront my internalized bias.

Here is the darkest part of my story, the part that makes me ashamed:

I was visiting a school for a book event. In the line of what appeared to be kindergartners, I saw one Black girl squirming and being silly along with everyone else. She wore a pink and purple and blue tutu that rode high on her round bottom. I thought, ‘She should know better than to wear a skirt like that.’ As soon as I thought it, I hated myself for it.

‘She should know better.’ She's a child just existing in her body. I placed a bias on her that assumed she was old enough to know that her body was different from other kids, old enough that she should police herself. How dare I?

Let's carry that moment out to its fullest extent. What would happen next if I truly believed the girl had done something wrong? Should she be pulled out of line and scolded for dressing inappropriately, ignoring the fact that children's clothes are not size inclusive? Would she get into trouble? Would she be made to change? Would she miss class? Would she fall behind? Would her grades slip and get her placed on a slower track? Would she get into more trouble for more absurd things? This is the ripple effect of adultification bias.

A study from the Georgetown Law Center on Poverty and Inequality called ‘Girlhood Interrupted: the Erasure of Black Girls’ Childhood’ describes adultification bias as the perception that some children are more adult, more mature, more responsible, and more knowledgeable than their age would suggest. The study found that adults view Black girls as young as the age of five as less innocent and more adult than their white counterparts, which results in their believing that Black girls need less nurturing and less protection.

There are numerous metrics that feed into this: skin color, height, voice, body shape, size, and weight. I knew firsthand that Black girls were being judged and punished for being too something—too tall, too loud, too big. I didn't learn this in a vacuum. It is part of our society, and it steals the joy and future from Black girls every day. That girl in her tutu could have been me. I saw in her my hair, my skin, my round belly, my joy, my silliness, and I saw how this bias had left a huge scar inside of me. Big was my response. If I couldn't heal myself, then maybe I could help create a world where girls never have to hurt like this.

Confronting your implicit bias is not an easy thing, but it is important ongoing work that we all have to do. My call to you—coming from me, an imperfect person who has flaws and makes mistakes—is to do the work in addressing and dismantling your implicit bias, not just for yourself, but for every child, every young girl, every young reader, every person who comes after you.”

Harrison finished her speech with thank yous and left to a standing ovation. Then Newbery winner Dave Eggers found himself trying to follow what he called the best speech he had ever heard in person.

The author of the medal-winning title The Eyes and the Impossible struck a different tone immediately, after dropping the Newbery Medal on the floor while trying to take it out of its case and noting that he was already living his nightmare and messing everything up.

The author of the medal-winning title The Eyes and the Impossible struck a different tone immediately, after dropping the Newbery Medal on the floor while trying to take it out of its case and noting that he was already living his nightmare and messing everything up.

The laughter continued as he described his unusual book ideas as an elementary school kid and the weirdness. He talked about the amazing teachers he had and their impact on his life path and career. Then he spoke about how his mother would be "pleased and astonished" to know he became a writer, and their connection to books and this award.

“God, she loved the Newbery,” he said. “She loved books, loved libraries. She took us weekly into the library in our town where the basement children's section had just been redecorated to look like a forest, a forest of stories. I spent much of my childhood there with my mom, who tried to guide me toward the Newbery winners, but who accepted my book choices, which were usually, yes, about monsters.”

But his mother did not live to see her son’s book among those Newbery titles in the library. She passed away at age 51, Eggers said, adding that his father died at 55.

“Now I'm 54,” he said and paused to regain composure before chastising himself for choking up. “This is a fact that astounds me every day. I have never told anyone this, but I vowed if I made it past 50, I would write whatever the hell I wanted to write.”

After the long ovation that followed, Eggers continued: “So when I hit 50, I wanted to do something not so logical for a person of five decades, and that was a story about a dog who ate garbage and lived in the hollow of a dead tree in an urban park by the sea. A story about the ecstasy of moving fast and the unreliability of ducks. I wanted to write about friendship—such a hard thing to write about—and about sacrifice and honor and the vaulting joy of being depended upon. I wanted to write about art and about a cruel and gorgeous, gray ocean, and about the greatest city park the world has ever known, San Francisco's Golden Gate Park. And about how necessary these wild lands, even wild lands surrounded by grids of tan and white homes, are. And about how, because we are alive and free, and so lucky to be alive and free, we must luxuriate, and exalt, in this life and its freedom.

“My secret that I can now divulge is that The Eyes and the Impossible was my love letter to being alive past 50, and how I sometimes cannot believe my luck. To see what I see, to love who I love, to be able to convey these things in a book that I honestly cannot believe made sense to anyone. This is the most personal book I’ve ever written, and it’s also the weirdest, and the fact that librarians of this great nation have recognized it … means to me, and should mean to any writer anywhere, that if we forget our dignified selves and write with a kind of untethered abandon, sometimes that’s exactly what a reader wants.”

He thanked those in his circle and the greater publishing world who work to get new voices into the industry, to let the strange stories have some space on the shelves, and he ended by thanking the librarians who protect and share those stories.

“Books are simply souls in paper form,” he said. “So when we accept a strange book, we accept a strange soul. We say that soul, however unusual or unprecedented, how reckless or flawed, belongs among the other souls of the world. And once this soul has been welcomed to the library—which is nothing less than a repository of souls—it cannot be unwelcomed.

“More than that, because of you, these souls will be protected. When the small-minded ban books, they are banning souls. They are removing certain voices from the chorus of humanity and the chorus of history. And it is librarians who are tasked with making sure these souls are not removed, that they always have a home and always have a voice. Librarians are the keepers and protectors of all history’s souls, its outcasts and oddballs, its screamers and whisperers, all of whom have a right to be heard. No pressure, but we count on you to save us all, to protect us all, to preserve us all. Thank you and godspeed.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!