Connecting Censorship and the 1960s Freedom Schools

Author Ashley Hope Pérez teaches the 1960s movement to help her Ohio State University students understand the impact of the current book bans and learn how to take action against censorship now.

|

Freedom Schools provide a framework for advocacy now, according to Pérez. |

As author Ashley Hope Pérez continues to deal with the censorship of her 2015 novel Out of Darkness, she approaches it the same way she does every difficult situation she did not choose—by finding the opportunity for action.

She has been outspoken in advocacy, editing Banned Together: Our Fight for Readers’ Rights, an anthology featuring fiction, memoir, poetry, graphic narratives, essays, and more from 15 YA authors who explore book bans and aim to empower teens to fight back. But she wanted to do more. As an associate professor at Ohio State University, she designed a class called Banned Books and the Cost of Censorship.

She has been outspoken in advocacy, editing Banned Together: Our Fight for Readers’ Rights, an anthology featuring fiction, memoir, poetry, graphic narratives, essays, and more from 15 YA authors who explore book bans and aim to empower teens to fight back. But she wanted to do more. As an associate professor at Ohio State University, she designed a class called Banned Books and the Cost of Censorship.

“My goal was really to use the current situation of book banning and educational censorship as a framework for helping college students recognize opportunities for advocacy, but also to see how concepts like citizenship can get hijacked,” says Pérez, who is teaching the class for the third time in the 2026 spring semester.

During the first two classes she taught, she realized that as the students go through the course, they hit a point where the current reality of the situation feels discouraging and overwhelming. What’s the point in trying when the battle feels unwinnable?

As a way to attack an issue that seems intractable, Pérez uses a framework called Impossible Project, which aims to prepare students for justice work by helping them learn to “build true collaboration, enact collective unlearning, nurture critical imagining, and discover purpose in and through justice work.”

Looking at educational censorship and book banning, students map problems, create a theory of change, and develop a collaborative project they are passionate about that tackles some aspect or cause of the issue.

“We know that no one project will be the full change, but we dream bigger than reactions to harm,” says Pérez.

Even with the Impossible Project framework, as she taught the class for the first time, Pérez realized students needed an example to “dig into.” While others may have looked toward historical times of censorship or attacks on freedom of speech such as the Scopes Trial, Nazi Germany, or the McCarthy era Red Scare, Pérez instead turned to the Freedom Schools of the 1960s.

According to the Civil Rights Teaching website, “The Freedom Schools of the 1960s were first developed by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee during the 1964 Freedom Summer in Mississippi. They were intended to counter what Charles Cobb refers to as the ‘sharecropper education’ received by so many African Americans and poor whites. Through reading, writing, arithmetic, history, and civics, participants received a progressive curriculum during a six-week summer program that was designed to prepare disenfranchised African Americans to become active political actors on their own behalf (as voters, elected officials, organizers, etc.). Nearly 40 Freedom Schools were established serving close to 2,500 students, including parents and grandparents.”

While some may not see the connection between the Freedom Schools and book banning, Pérez can draw a direct line.

While some may not see the connection between the Freedom Schools and book banning, Pérez can draw a direct line.

“There is quite a direct connection, because censorship and the restriction of knowledge and the contraction of spaces of learning and inquiry are at work in both,” says Pérez, who uses The Freedom Schools by Jon N. Hale and resources from Civil Rights Teaching (civilrightsteaching.org), a product of Teaching for Change, in the course.

“When we look at the educational realities in the South and the 1960s and when we look at the goals of book banners and legislation that targets difficult topics or important discussions in classrooms, those projects are connected. When you constrain dialogue and exploration of facts about our history, you constrain young people’s ability to imagine change.”

The comparison not only shows current students what is possible, but, according to Pérez, offers hope for change and a more just, free world eventually.

“Researchers, historians, see that moment as having a critical role in fueling the civil rights movement,” she says.

Calling the schools a “powerful example” for her college students, says Pérez, “This exploration [is] really a turning point. It anchors students’ commitment to do something that matters with their project, to think beyond reaction, and to focus on transformation. I find it, personally, very powerful and moving.”

Youth in the 1960s acted in the face of what seemed to be insurmountable injustice, knowing they couldn’t immediately change school segregation or unequal funding, Pérez says. “But rather than being frozen in the face of that, they [asked], What can we do to transform that reality—creating experiences outside of public schools for kids to question and explore and create or experience intergenerational learning and a sense of leadership in their own communities.”

Those in the schools knew that access to books was a key part of their education and ability to be full citizens. In the Civil Rights Teaching resources, an 11-year-old boy is quoted in a newspaper: “Negroes ought to have the right to vote for justice, equal rights, freedom, jobs, we need better books to read.”

|

Ashley Hope Pérez (center) teaching Banned Book and the Cost of Censorship, a class she created at Ohio State University.Photo by Jodi Miller |

To Pérez, there is another important element to the Freedom Schools that connects to current times—the need to create a space for learning and conversations not happening in schools.

“We’re in a time where we shouldn’t stop suing, we shouldn’t stop speaking up in school board meetings, and all of those things, but we also need to be thinking what else can we do to create spaces where we can open the discussions that politicians and right-wing groups are looking to close....

“I would love to see a vision of what it looks like for community members to host spaces where young people can have the difficult conversations or talk about the topics that they want to. The contraction and resistance is not coming from students. It’s adults and communities who want to see these topics swept aside.”

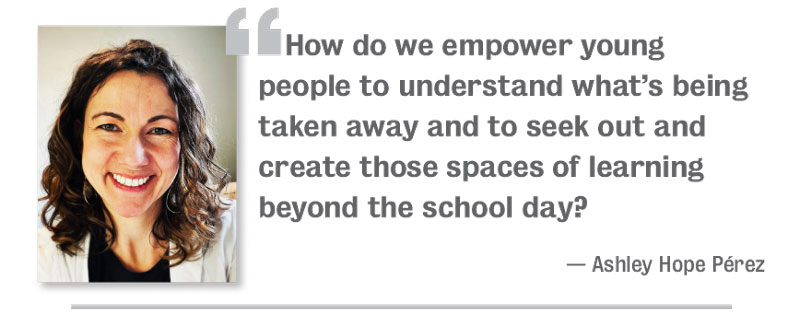

Educators are chilled by legislation and fear of consequences, Pérez says, asking, “How do we empower young people to understand what’s being taken away and to seek out and create those spaces of learning beyond the school day?”

The kids in the Freedom Schools of the 1960s didn’t initially know what they weren’t being taught any more than the K–12 students today know what is missing from their libraries.

“Our reality was impossible to imagine for those advocates, and yet they still took actions that created a new set of possibilities,” says Pérez.

“Just like those Freedom Schools could not on their own alter the reality, what we’re doing cannot on its own alter reality,” she says. “But we want to do things that open up possibilities for the future and for others who come after us.”

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!