SLJ Talks to Kiese Laymon About His New Picture Book City Summer, Country Summer

Kiese Laymon, award-winning author and MacArthur Fellow, is out with a new picture book. City Summer, Country Summer celebrates the deep bonds of friendship forged among three Black boys on a summer journey to visit their grandmothers in Mississippi.

I was an elementary school librarian for 10 years, and as soon as I heard about Kiese Laymon’s new picture book, City Summer, Country Summer, I couldn’t wait to read it. The book is based on a collaborative photo essay between Laymon and photographer Andre Wagner published in 2020. It takes place in Mississippi, where Laymon and I both grew up. I was excited to see how Laymon—the author of the award-winning Heavy: An American Memoir, the autobiographical essay collection How to Slowly Kill Yourself and Others in America, and Long Division, who is also a 2022 recipient of the MacArthur Fellowship—would reinvent his essay in a picture book. Once it arrived, I marveled at how tenderly Laymon explores love and friendship between young Black boys.

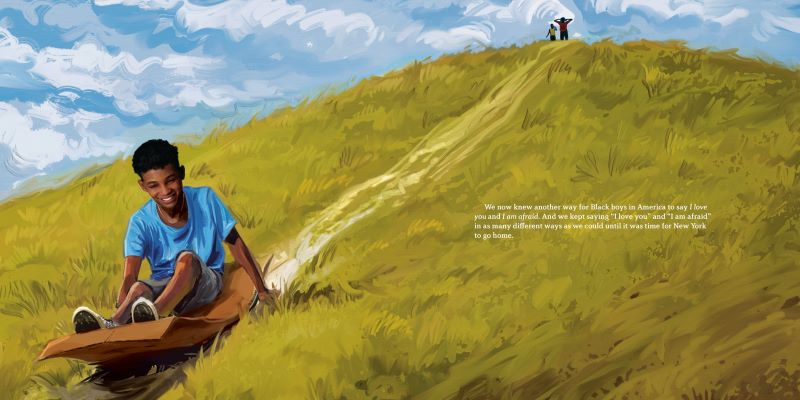

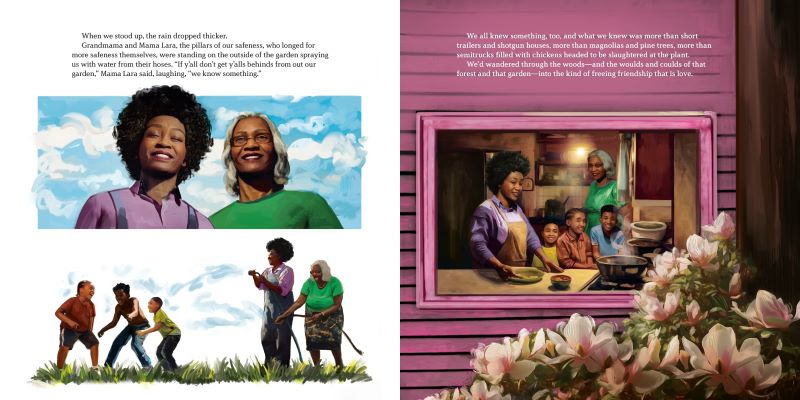

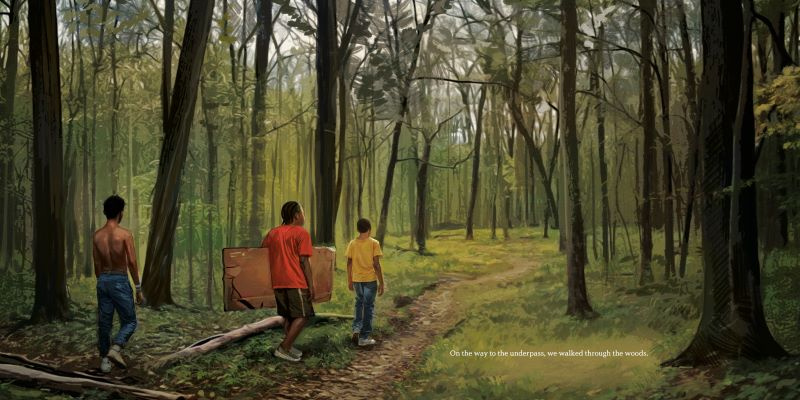

City Summer, Country Summer has gorgeous illustrations, courtesy of self-taught digital artist Alexis Franklin. In it, three boys, one of whom is from New York, visit their grandmothers in rural Mississippi. As the trio explore the woods, the surrounding countryside, and their grandmother’s gardens, they develop an unspoken closeness. Ever since my copy arrived in April of this year, I've thought about how I would introduce this book to a classroom. Maybe we'd talk about what it's like to visit places different from our own hometowns, or what it would be like for someone from New York to go to the country. Maybe we'd talk about visiting grandmas in the country, where there's a slower pace of life than in the city. Maybe we’d cite other books that involve kids visiting one another, or the fable about the city mouse and the country mouse. I know we’d discuss how, at its core, this is a book about the importance of connection, and that we’d discuss why it’s important for all of us to find people we love, can connect with, and can share our feelings with.

Laymon, age 50, lives in Houston, where he’s the Libbie Shearn Moody Professor of English and Creative Writing at Rice University. This conversation has been condensed and edited.

Deirdre Sugiuchi: How did you decide to write a picture book?

Kiese Laymon: An editor from The New York Times sent me these Andre Wagner photographs of young Black boys in New York City back in 2020 and was like, “We want you to write a complementary essay.” At that time, in the middle of the pandemic, a lot of people I knew felt like this was the closest we’d ever been to some semblance of collective action and collective freedom in this country. We were protesting the devaluing of Black life in the nation, and there was a moment when it seemed like we were about to turn the corner.

I know what The Times wanted—a description of the kids and the playfulness. Partially because it was 2020, and partially because of where we were in the world post George Floyd’s murder, I knew prose poems weren’t gonna work, but I was like, “I’m gonna do it anyway.”

I wrote this sort of prose poem about the kids I saw in those photographs. Ultimately, I just wanted to get those kids in the photographs to the garden playing Marco Polo, because I used to always go to my grandmother’s house for the summer and play that game. Then it came out, and people who didn’t really like some of my other work really loved that piece, and I got contacted about trying to make it into a book.

Namrata Tripathi, my editor at Kokila, reached out to my agent [PJ Mark] with this gorgeous mockup of what a picture book of that NYT essay might look like. PJ and I were stunned. It was so incredible to see the possibilities that Namrata saw. Initially, the collaboration was with Namrata and Jasmin Rubero, the extraordinary art director at Kokila. Eventually, we got with Alexis Franklin, the illustrator of my dreams, and we collaborated in this really fulfilling way for two years.

At that point, I’d been able to think through a little bit more how I wanted the book to be different than the article. Also, when I’m collaborating with people, I don’t want to be too heavy-handed. I was like, “Alexis, here’s what we have in terms of words. I want to see what you want to make out of it and then let’s just collaborate based on that.” Alexis understood unspoken things I was trying to say about intimacy, about anxiety, about the importance of environment and gardens and woods in Mississippi. And she felt that street, my grandmama’s street, Old Morton Road. She just made it beautiful.

It was the first thing I wrote where I didn’t feel any anxiety about it. If you like it, you like it. If you don’t, you don’t. I didn’t feel like I feel with everything else I’ve written, like, I’m opening up my life and letting people look in at parts that I maybe shouldn’t. With this one, I was just like, “Yeah, you’re gonna look in on a part of my life, part of my imagination, these characters out there, just living, trying to be beautiful, and trying to touch and to love.”

DS: Did the words change once you got her drawings?

KL: Absolutely. Because, in the first version, I wrote about whether you were from Jackson, Mississippi, or New Orleans, or Birmingham, or whatever. With [the book], I wanted to talk about the way New York centers itself in the country. I wanted to talk about the way Chicago people are country to New York. California people are country to New York, especially because a lot of the California people and the Chicago people from the Deep South, or deep parts of Texas, are the people who left [the South] to go out West for those defense jobs way back in the day.

I took out some sentences, when they’re in the woods [when New York hides from his friends], to magnify the drama of a boy being missing, like they can’t find him. So, it’s kind of funny in the book, but in my era, kids went missing. People were getting snatched up all the time. People thought they got picked up by, like, Wayne Williams, you know what I’m saying?

DS: For sure. I’ve been thinking about, how, as a librarian, I would describe this book. Of course, it’s a kids’ book for all kids. But you’re particularly speaking to Black boys dealing with emotions. Can you talk about why it’s important for Black boys, for all boys, to have a book about feelings in this moment?

KL: Man, I could talk about this for days. You look at the way boys who are now men are gleefully destroying the most vulnerable people and things on earth. And part of that is because they have not been encouraged, have not been taught, and have not decided it is valuable to talk about what love and fear actually mean in their bodies, and what a lack of reckoning with love and fear actually does to other people’s bodies.

So, yeah, this is for those Black boys, but I’m also talking about the way we make boys in this country. There’s a lot messed up in this particular country and world, but one of the most messed-up things is the way we make boys. I wanted to look through my experience and imagination as a Black boy, and those kids’ relationships to the earth and to each other, and how they’re gonna be different than other kids. But I don’t want anybody to get it twisted. I think that, in some way, this book is an attempt at a corrective and it’s an attempt at honoring the ways boys can love each other and do love each other. But we need to extend that love and be able to talk about it and let that govern our ability to confront when we’ve been abusive, confront when we’ve wanted to hurt vulnerable people. I don’t want to be beating people over the head with that, but that’s really what that is about when those kids are talking about “We found new ways to say I love you” and “I’m afraid.”

I really think we need to be contending with that as men every day of our life—in group, out of group, in psychology sessions and outside. But look at who’s running the country—we ain’t trying to have conversations about what we actually are afraid of. We’re not trying to have conversations about what we actually love and what that necessitates, and how we fail at love. If you thought that was cushy stuff that we never needed to talk about, just look at the world now.

DS: You recently lost your grandmother. This book is a tribute to grandmothers, right? Can you talk about her?

KL: If I have a writerly superpower, it’s that I was my grandmother’s grandchild. I want to honor her in everything I make. I thought a lot about what it means to frame this narrative with grandmothers. What I didn’t want to do was, like, imply that the grandmothers in the story were fairly treated in Mississippi. So that’s why I say at the end, they, too, were in need of safeness themselves.

The whole book is really my grandmother’s garden. My grandmother made that garden, and I wanted the kids to get lost in it. I wanted a book that embraced Black boys being lost, and the playful experimentation it takes to find your friends and yourself when you’re lost.

Sometimes we think about loss, we think about coming out the other side of it scarred or [with] some sort of dread. But sometimes people who love you can make really layered, wonderful things that you can get lost in, and you can come out better. And for me, the garden was one of those things my granny made that I could explore and come out feeling better.

I don’t think we talk enough about grandmothers. My grandmother was a very disciplined, responsible person, but one of the reasons I write about her so much is because I saw her play. She would spray you if you got in that garden. My godmother, the other grandmother character I write about, was called Mama Lara. She was my granny’s best friend. And Mama Lara loved wrestling. We used to watch wrestling together. So, I wanted to make a book where you could see some of the playfulness and honor what they both made.

DS: Can you talk about the Catherine Coleman Literary Arts, Food, and Social Justice Summer Program, which you established in honor of your grandmother?

KL: Every year we get 30 kids in Jackson for a week, and they get to stay in the dorms at Jackson State. We bring in all sort of practitioners, from foodways, to racial justice, to people who make maps, and photographers. And the [kids] spend the whole week learning about each other and doing creative writing and revision but also learning about foodways at home.

Because Jackson State is an HBCU (Historically Black College and University), and so many people don’t know what HBCUs do, I wanted to create more ways for people to engage with an HBCU. I was born on that campus when my mother was a student, and my mother worked there for most of my childhood. And I always believe in being useful to people already doing the work, like in the Margaret Walker Institute at Jackson State University. I just trusted them with the resources, and I gave them a little bit of the vision, and they’ve been on the ground making it happen. It’s been wonderful.

I got Samuel, one of the kids who’s been in the program for two years, to narrate the audio book. It makes more sense for me to get a kid who’s been coming to my grandmother’s camp [the Catherine Coleman program] every year, learning about foodways and justice in Mississippi history [to be the narrator]. Samuel has a voice—it’s so Jackson, and it’s so Mississippi.

DS: The program keeps you connected to Mississippi, right?

KL: My family is there, but yeah, that’s the way I stay connected to young people in Mississippi.

Deirdre Sugiuchi is an assistant editor at The Rumpus, a contributing writer at Electric Literature, and a former public school librarian. Her essays and excerpts have been featured in Action, Spectacle, Literary Hub, Salon, and other places. She recently completed Unreformed: A Captivity Narrative, a finalist in the 2025 International Creative Nonfiction Competition hosted by Vine Leaves Press, which will publish her memoir in 2027. She lives in Athens, GA, with her husband and dog. Find her on BlueSky, Instagram, and Substack.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!