In Virtual Summer Programming, Librarians Prioritize Human Connection

Libraries' initiatives range from loosely structured book clubs and virtual places to talk to meeting children’s fundamental needs: providing Wi-Fi and reading material.

Every spring, Tamara Cox leaves her library at Wren High School in Piedmont, SC, to make the five-minute trek across the street to Wren Middle School.

This annual ritual lets her get to know the rising ninth graders and introduce them to the resources available at the high school library. She usually booktalks 15 titles and allows the students to choose one they’ll read over the summer. The books are checked out to them, and the students discuss them in the fall with a freshman teacher.

“It’s just a way for us to connect with them and start promoting reading before they even come to us,” says Cox.

But Cox’s school, like so many others around the country, closed its doors in March due to COVID-19. Around the same time, public libraries began to close, and while some have reopened with new guidelines to help protect patrons from the coronavirus, in most cases typical summer programming for kids has been scrapped in favor of online offerings.

|

From the left: Tamara Cox this year from her dining room table; Preparing summer reading titles in her school library last year.Photo by Michael Cox (courtesy of Tamara Cox); Photo by Madison Haynes (courtesy of Anderson School District One) |

Libraries’ efforts during the summer of 2020 range from offering myriad virtual programs, including simplified summer reading programs and loosely structured book clubs, to creating a place to talk and meeting children’s fundamental needs: providing Wi-Fi and any reading material.

“This is just not a time to be encouraging large crowds in confined spaces,” says Megan England, the branch manager at the Scottsville Library in Scottsville, VA, a small town about 30 miles south of Charlottesville.

England, who also writes YA fiction under the name M.K. England, says their small library had no choice but to go virtual with its programming this summer.

“Our branch is the tiniest branch in the system, and there is not even six feet of distance between the front door and the front desk,” says England.

The Scottsville Library is part of the Jefferson-Madison Regional Library system, which serves an area the size of Delaware. During the summer, the various branches host large-scale regional events for kids.

But that isn’t happening this year. Instead, England’s library and others in the system are offering programming for children online. Now, the musicians and scientists they had planned to bring in will be doing virtual presentations.

The smaller, library-specific programs, such as presentations on résumé writing, are also virtual this summer.

England says that despite the hardship inherent in being physically closed, there are some benefits for patrons throughout the region.

“It means that the programs that I offer at my little branch at the southern tip of the county can now also be accessed by people throughout our entire library system,” England says.

|

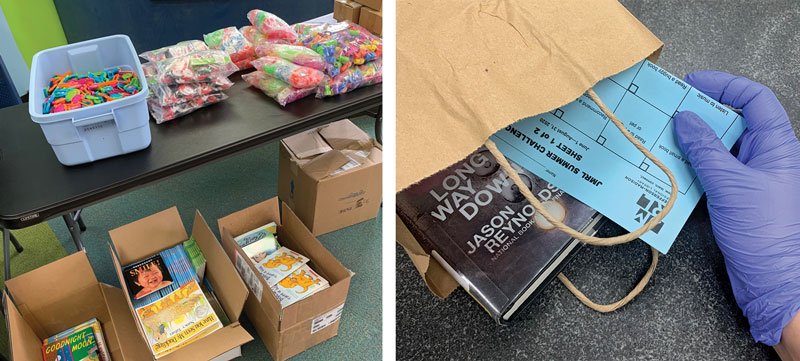

From the left: Summer Reading in a Bag offerings from Normal (IL) Public Library include books, paper activities, and a prize; Every book bag from Scottsville (VA) Library has a reading challenge sheet.Photo courtesy of Normal (IL) Public Library; Photo courtesy of Scottsville Library |

Just keep them reading

At the Normal (IL) Public Library, the main goal is making sure young patrons keep reading this summer.

“Our biggest concern is just access to books. We want to make sure that they have things they want to read,” says Jennifer Williams, who’s been the children’s librarian there for 18 years.

In early June, her library, which is about 130 miles south of Chicago, started curbside service after being closed for roughly two months. During this time, kids could check out ebooks and audiobooks, but Williams says those have never been very popular with young readers.

“So we really like being able to offer a physical book when we can,” says Williams, who just a few months ago took on the interim tech service manager position in addition to her primary role. This means now she has to juggle managing the library’s collection and all of its databases in addition to overseeing the summer reading program.

The program usually attracts about 5,000 people. Last summer, 3,600 kids participated. It takes a lot of advanced planning to run smoothly.

This year, the library is simplifying its summer reading challenge. Instead of three or four different options based on age or grade, the 2020 challenge is the same for everyone. Readers are asked to log online either the number of books or pages read or the time spent reading. The prizes that are usually awarded are being replaced with virtual badges and tickets that will be put into a drawing for various rewards that will be given out at the end of the summer.

Typically, the library asks local businesses to provide the prizes, but this year, in a nod to the challenging economy, things will be a little different.

“It’s pretty much just going to be a variety of $10 gift cards, where in the past we’ve asked for sponsorship or prizes or coupons from local businesses,” says Williams. “That was one of the first things we decided—that we didn’t want to make that ask this year. It didn’t feel right, and instead, we’re turning things around and purchasing from them when we can.”

The summer reading program at the Milne Public Library in Williamstown, MA, will also be virtual this year, but children’s librarian Kirsten Rose says that tracking reading isn’t as important now.

“I’m trying to meet people where they are, and I suspect most kids are sick of screens and needing something to do,” says Rose.

In July, Rose started posting simple activities weekly that kids can do on their own.

“I’m hoping people will feel like they can be flexible with them and kind of take them and adapt them to whatever they want to do or however they want to do it,” she says.

The activities include things such as writing prompts, crafts ideas, and recipes.

“I don’t want to have people go out and buy a whole bunch of supplies so you can do this activity,” says Rose. “I’m trying to make them so that they can just be done with stuff you have around the house or you can substitute the things you do have.”

School librarians step up

During a typical summer, most school librarians use the time to recharge for the coming academic year. But this year, some plan to put in a lot of work for free. They’re worried about their students, who in most cases haven’t set foot in a classroom for months, and they want to make sure they’re reading and engaged in learning until school resumes in the fall.

When Kate Pritchard realized her community’s public libraries might not be open for the summer, she started planning for ways to support her students.

Pritchard is the middle and high school librarian for the University School of Nashville, located on the campus of Vanderbilt University. The private K–12 school occupies one building and has a little more than 1,000 students.

In the spring, Pritchard says, her school, which serves a “broad range of families economically,” began discussing ways to help students during July and August. There was no pressure to step up, she adds. Staff could choose whether or not to volunteer their time.

In mid-June, the school library began offering curbside pickup service twice a week. The school is also hosting virtual camps, and Pritchard planned to lead one on genealogy with a colleague if there was enough interest.

Pritchard, who like most staff at the school is on a 10-month contract, decided to start a couple of book clubs in March and keep them going once school ended. One serves students in fifth and sixth grades, and the other is for students in seventh and eighth grades.

Starting the clubs helped to provide Pritchard with a chance to interact with students she missed, particularly those who love reading.

“I didn’t really have a way of seeing kids the way that I normally would in the library, just casually talking about books in the hallways, that sort of thing, and so I wanted to offer the book club as a way to connect,” says Pritchard.

Students in each book club voted on what they wanted to do during their weekly meetings. The younger kids wanted her to read to them, while the older ones chose to just get together and talk.

“Sometimes we spend a lot of time talking about books, and then sometimes they just want to talk about anything else, and that’s fine,” says Pritchard. “I don’t feel the need to really direct that conversation too much because it’s just really meant to be a fun, optional, social thing.”

The Wi-Fi lifeline

Julie Stivers wanted to keep that connection with her students at Mount Vernon Middle School in Raleigh, NC.

“The thing that worries me the most is we just haven’t seen them,” says Stivers. “It’s been so long.”

Mount Vernon Middle is an academic recovery school. Students from all over the district are referred to it after struggling to keep up in their home schools.

“With all of the barriers that COVID-19 has put up in terms of education, in some ways it has provided access if you’re in a district like mine that gave devices and hotspots to every student [who] needed them,” says Stivers.

That has allowed Stivers to stay in touch with her students, who she says were “failed” by their other schools.

Before school closed, a group of students met in the library during lunch to discuss anime. Since the coronavirus forced her school to shut down, Stivers has continued to meet with those students. They get together virtually to watch a couple of anime programs on Wednesday and Friday afternoons.

Stivers is keeping that going, and she’s also added a writing club and a STEM group for any student who wants to participate. Students are encouraged to share their creative writing or to design something. Stivers was able to bring the library’s 3-D printer home and plans to print the items students create and mail the finished products to them.

“It seems kind of silly to be doing three things during the summer, but if there aren’t as many physical things that they can do, I just want to give the option,” says Stivers. “Because we don’t know what’s happening with public libraries, I feel like we do have to take on some of the programming roles that maybe [they] would be doing, or we need to work together more.”

Wren High School was able to continue its summer reading program for rising ninth graders this year, thanks to technology and a partnership with a public library.

Since she couldn’t go to Wren Middle School and do booktalks, Cox had freshmen teachers record booktalks and post them on social media. Then students were able to select one of the 12 ebooks presented courtesy of the Anderson County Library System.

Cox says she appreciates the help from the public library, but she’s still worried that some of her students will falter a bit without the face-to-face contact.

“Now we’re relying on being able to get the information to them through email and social media, and so I know there’s going to be kids that maybe don’t have access or consistent access, and I’m worried that they’re going to be left out,” she says.

That’s a common concern among librarians who are trying to keep summer programs afloat strictly online. The latest report from the Federal Communications Commission on internet access in the United States found that as of 2017, 21 million Americans lacked broadband internet access, and the head of the FCC has acknowledged there’s a good chance that number is underestimated.

England’s library, which sits at the nexus of three rural Virginia counties, allows patrons to access free Wi-Fi from the parking lot. But staff don’t believe that’s a practical way for kids to access summer programs.

Still, they say, the parking lot Wi-Fi is popular with patrons, perhaps because once you cross the line into another county there is no broadband access at all.

“The lines are just not run,” says England. “Those are the patrons that I think the most about and worry the most about during this time, because I feel like we’re just not able to provide the same level of service across our entire population. That’s really disappointing, and it’s something that really weighs on my mind right now.”

Freelance journalist Marva Hinton is a contributing editor to Edutopia and the host of the “ReadMore” podcast, an interview show that primarily features authors of color.

Freelance journalist Marva Hinton is a contributing editor to Edutopia and the host of the “ReadMore” podcast, an interview show that primarily features authors of color.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!