Solid Stories: Why Board Books Are Key Developmental Tools

The science behind board books, a brief history of the format, and a look at the publishing market.

|

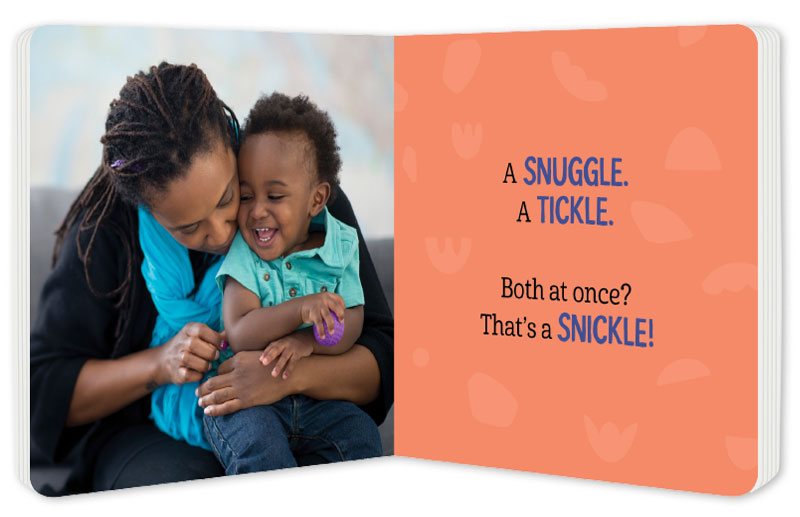

Give Me a Snickle! by Alisha Sevigny (Orca) |

So often board books are like the poor second cousin to picture books,” says Rachel Payne, coordinator of early childhood services at Brooklyn Public Library. She has heard parents make comments like, “I just like to stick with real books.”

Adult opinions aside, board books are a solid hit with tots and sturdy sellers in the publishing industry. They’re also a powerful tool for neurodevelopment in young children.

When did board books become a big thing? Nielsen numbers indicate skyrocketing sales since 2010, from 17 million board books that year to 31 million in 2015. Cecily Kaiser, Penguin Workshop associate publisher, RISE and World of Eric Carle, counted 630 original board books published in 2022.

The science behind board book learning supports the market boom. “The number one most important thing about board books is the pages’ thickness, because babies and toddlers don’t have the fine motor skills to turn paper pages,” says Caitlin Gallingane, clinical assistant professor in the University of Florida’s College of Education. That enables the development of “concepts of print”—how to hold a book, how to turn pages. Babies learn these basics not just by seeing, but by getting their hands on books and mimicking their grown-ups.

Then there’s neural pathway-building content. Gallingane points to concept books “that are just page after page of different categories of stuff, and it’s pictures with labels.” Books like My Big Word Book by Roger Priddy are set up to encourage whoever is reading to “point and say.”

Board books that encourage the asking of questions (e.g., Karen Katz’s Where Is Baby’s Belly Button?) nudge caregivers toward interactive “dialogic reading.” And narrative books expand a one-year-old’s vocabulary, Gallingane says, since they almost always feature more sophisticated language and language patterns than in everyday speech. They’re designed to inspire “call and response” and lots of repetition. “Repetition is crucial,” she says. “It takes kids at least 10 exposures to a word to learn that word.”

There’s a good reason why little ones want to hear a story again and again (and again!), says Panayiota Kendeou, a professor in the psychological foundations of education program at the University of Minnesota. “[Once young children] have an existing mental model about this story, that frees up resources for them to pick up new things they may not have been able to discern the first time around.”

A tot won’t get the same impact from a picture book or YouTube storytelling, Gallingane explains, because language retention increases with multisensory input: “Being able to look at something, hear something, touch something, say something, all at the same time, reinforces that word and that concept more strongly.”

Board book damage should be expected. Publishers can test and use the sturdiest stock, and still, “If you give this to a determined three-year-old, those flaps will come off,” says Meredith Mundy, editorial director at the Abrams imprint Appleseed. She calls the increase in hand-eye coordination and lessons in gentleness and cause-and-effect “just kind of priceless and worth the wreckage.”

In fact, that sort of fun is part of the power of board books. “A child is not going to learn to read if they don’t want to,” Gallingane says. They need positive associations: a warm lap, a comforting embrace, a caregiver’s undivided attention. Being able to skip around in a book gives toddlers a sense of competence, control, and mastery, she adds. All these feelings can be addictive, fostering a habit of interacting with books.

There’s another evidence-based benefit to the specialized board book format: “It really reminds parents that this is a specific age that has its own needs in terms of how we are speaking to kids,” says Deborah Farmer Kris, a parent educator and author of the “All the Time” series about emotions. Just by existing, board books communicate to parents that preliterate—and preverbal—children benefit from reading.

Debates and questions

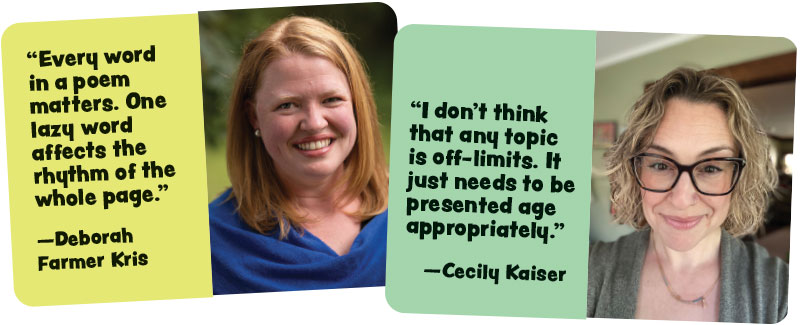

Not everyone agrees on what a board book should look like, however. Kris is a fan of “a spareness” of pictures and text, not the busy graphics of “something that’s been a TV show.” Good board books are like poetry, she says: “Every word in a poem matters. One lazy word affects the rhythm of the whole page.” She dislikes board book versions of already published picture books, such as Ludwig Bemelmans’s Madeline,that have had their language truncated and illustrations cut down.

Not everyone agrees on what a board book should look like, however. Kris is a fan of “a spareness” of pictures and text, not the busy graphics of “something that’s been a TV show.” Good board books are like poetry, she says: “Every word in a poem matters. One lazy word affects the rhythm of the whole page.” She dislikes board book versions of already published picture books, such as Ludwig Bemelmans’s Madeline,that have had their language truncated and illustrations cut down.

Kaiser also has strong views about some format adaptations. “I find the board books that look like board books and feel like board books and are totally for adults kind of a travesty. I feel like it’s cheating the audience,” she says.

Cynthia Weill, director of the Center for Children’s Literature at Bank Street College of Education, reads over 300 board books a year and calls many of them “unremarkable.” But there are enough great ones that in January 2023, Bank Street announced the recipient of its biennial Margaret Wise Brown Book Award for excellence in literature for very young children. A jury of six people, with Payne on the inaugural one, looked for features such as sturdy construction, “rich, musical language that bears repetition and mimicry,” age-appropriateness, and whether a title invites interaction, promotes interplay, “reflects various identity characteristics,” is culturally appropriate, and evokes a mood. The 2023 winners were Give Me a Snickle! by Alisha Sevigny (Orca), for children ages 0 to 18 months, and Me and the Family Tree by Carole Boston Weatherford and Ashleigh Corrin (Sourcebooks)

for children from 19 to 36 months.

With the award, “we wanted to address the dearth of high-quality board books for young children and to let publishers know that an informed entity was watching and was going to reward high-quality work,” Weill says. To that end, certain categories are off the table, she adds, including books only appropriate for a four- to six-year-old, those that “come with a stuffed unicorn” or other objects, and “anything tied to TV or movies.”

When it comes to board book biographies, “Unless the language is rhyme-y, we’re excluding all that stuff,” she says. “A six-year-old may care about Jane Goodall or Frida Kahlo, but a two-year-old certainly won’t.”

Why not? Elizabeth Bluemle, who owns The Flying Pig bookstore in Shelburne, VT, and blogs for Publishers Weekly’s “ShelfTalker,” asks us to imagine a three-year-old hearing, “Serena is driven.... Serena and her older sister Venus love and respect each other, even though they compete with each other at the highest level of the sport.” In a PW blog post, Bluemle wrote, “Even if they understood the words, they lack the contextual experience to appreciate the complex set of emotions encompassed in those sentences.”

Joan Powers, who has edited books for young readers for decades, including Leslie Patricelli’s “Baby” series at Candlewick, sees things differently. “If your child learns about Jane Austen at two, why not?” she asks. Maybe they have some idea who Jane is and maybe not, but if they enjoy the reading experience, it’s a win, in her view.

Kris approaches nostalgia titles similarly, even if they’re not spot-on developmentally. “Honestly, if it’s appealing to you, you are more likely to read it to your child, and board books are all about the relationship between the caregiver and the child.”

|

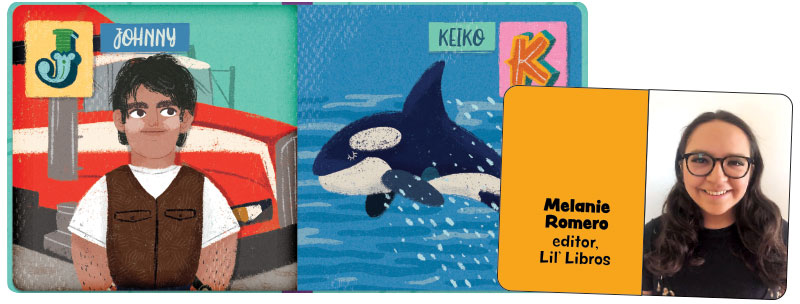

El ABC de las Telenovelas by Michelle Winters and Cris Winters. Art by Laura Díez. |

Melanie Romero is an editor at Lil’ Libros who grew up singing Selena songs and watching telenovelas with her mom. She says that the dual-language board books in the “Life Of” biography series celebrating people from Selena to Dolores Huerta aren’t supposed to be intelligible to toddlers standing alone. Rather, the act of explaining these cultural heroes “is really what keeps the glue of the family [and] breaks down that generation gap,” she says. “We cater to kids; we also cater to parents.”

Books that don’t hit the sweet spot for the 0–3 set can add a good deal of value in sibling situations, Powers says: “The older one can remember it and read it to the younger one, too.”

For this reason and others, Payne encourages parents to hold on to board books. “They can actually work at a couple of different points developmentally,” she says. She has also seen text-heavy board books adapted from picture books work well for older children “who have fine motor issues and maybe can’t handle paper pages.”

Still, Weill sees no reason to amplify books that only tickle adults when there are others that delight them and hit the sweet spot for kids. For example, she says, “Sandra Boynton books—they are commercial, but she’s a freaking genius.”

Kaiser calls board books requiring prior knowledge “disrespectful to the audience, frankly,” but says of subjects like feminism and equity, “I don’t think that any topic is off-limits. It just needs to be presented age appropriately.”

While Mundy hears her colleagues’ frustration with the quality of some board books, she doesn’t share it. Reflecting on titles likely to end up on clearance in a big box store, she says: “Parents who were looking for a bargain maybe wouldn’t buy a book otherwise. I’d rather have them have buy books than not.”

|

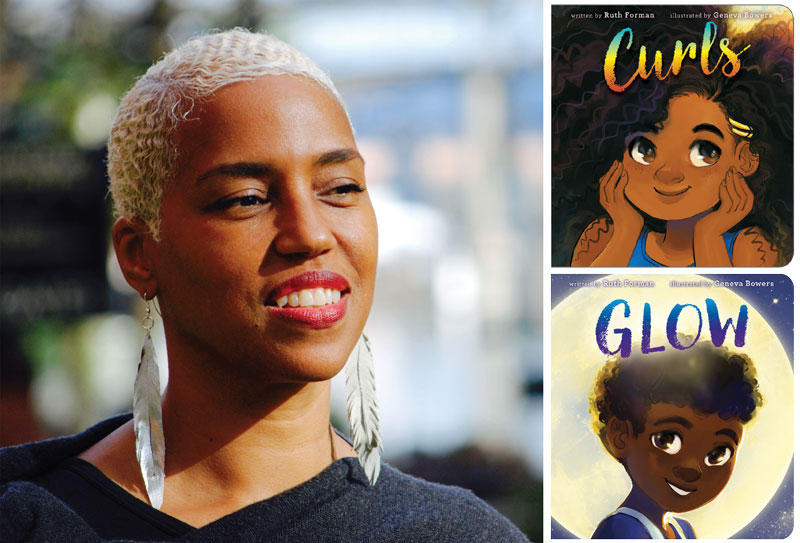

Ruth Forman, author of Curls and Glow |

Form, downspacing, representation, and recognition

With regard to trends in today’s market, Powers points to Steve Light’s Black Bird Yellow Sun (Candlewick) and says, “The art is really sophisticated and beautiful, and I think that’s something that’s happening more and more.” She adds that “extremes of size” may be coming down the pipe. They’re more likely to be tiny books than oversize ones, though, due to paper costs, she predicts.

Mundy has also seen projects scaled back lately. She’s careful not to use thinner paper that makes new books look less sturdy than others, “but sometimes you might decide, maybe this isn’t a 24-page board book, maybe this is a 22-page board book.”

Who’s on those pages has changed as well, including far more books with racially diverse characters. Payne sees improved access to bilingual Spanish board books but wants more—and more in other languages. “I think we need to go further in representations of disability,” she adds, and “people of color just going about their everyday business. It doesn’t have to be a cultural celebration.”

Romero maintains there is a long way to go in terms of diverse representation: “There are still so many stories to tell.” Lil’ Libros is doing that with titles like El ABC de las Telenovelas, a book by Michelle Winters and Cris Winters spanning decades of Spanish-language soap operas.

After author and poet Ruth Forman watched her three-year-old start “questioning her hair and her skin color,” a friend passed along a copy of Alonda Williams’s Penny and the Magic Puffballs. Forman witnessed the transformative power of her daughter seeing herself in literature. To find a book that positively impacts your child’s “sense of who they are and what they feel they can do,” she says, “it’s like a gift, it’s a relief.” After that, Forman started creating short books that “felt rich” as they depicted Black joy, including Curls and Glow, illustrated by Geneva Bowers (both S. & S.).

With so much variety and quality, Kaiser describes board books as unsung heroes. “If you have kids who are buying your middle grade books and your YA books, it’s because they formed a connection with books when they were young.”

Still, “there are no board book best-seller lists,” Kaiser says. “There are no board book awards issued by ALA. Our own industry has not caught up with what’s happening in it.” Nor do they get reviewed as much as other formats, Mundy adds.

Perhaps the Margaret Wise Brown Award is poised to change that. Kaiser says, “I’m equally thrilled and also hoping that this is just the beginning.”

Though board book sales took off in the 2000s, they are far from a recent invention. Allison G. Kaplan, distinguished faculty associate emerita at the University of Wisconsin–Madison Information School, used a fellowship from the Association for Library Service to Children to research the format. She points to A Peep at the Circus, published by McLoughlin Brothers in the 1880s, as a surviving early example, but it’s not even the oldest. “Metamorphosis books”—pop-up, lift-the-flap, or pull-tab—date to the early 1800s. The mid-1800s is when books for kids began to be published with thicker pages or on linen and sold with descriptors like “indestructible” and “untearable.” Cloth or rag books started booming around 1900, until World War II–era cloth rationing. In the late 1930s, titles by Margaret Wise Brown and others were printed on “substantial paper” and “extremely tough cardboard,” Kaplan says. But “the big publishers really didn’t want to deal with them because they weren’t considered to be a high quality kind of publication.” Even after the format’s popularity rose in the 1950s postwar boom, board books were still seen as novelty items and Hallmark-esque gifts. Things changed dramatically as the 1990s saw an increase in government investment in conducting and publicizing early literacy research, epitomized by the Becoming a Nation of Readers report. “There was a huge focus on Head Start and universal pre-K,” adds Cecily Kaiser, Penguin Workshop associate publisher, RISE and World of Eric Carle. This, alongside “a pop parenting message that if you don’t get in there before your child is six or seven, you’ve lost the opportunity.” This mentality was part of a larger cultural shift to intensive parenting. “That drove attention and that drove the market and that drove sales.” A misunderstanding of the term “early literacy” also likely played a role, Kaplan says. Lingering Cold War anxiety around American competitiveness plus parents’ fear for their children’s future amid increasing economic inequality turned “early literacy” into “read earlier.” Books originally written for first graders increasingly got the board book treatment. And publishers discovered that they were recession-proof: “What was untouchable during those moments of downturn was that board book market,” Kaiser says. On Publishers like Abrams launched imprints, such as Appleseed. Innovation followed, including easier-to-clean, safer coatings like UV lam and aqueous matte. The last U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission press release describing lamination peeling off a book and becoming a choking hazard dates to 2001; since then, most recalls have dealt with bells and whistles like plastic frog eyes. Editor Joan Powers points to rounded corners as another enhancement, along with the spot UV that created the shiny silver trail on the cover of Slow Snail by Mary Murphy (Walker). In less than a generation, editors went from holding a picture book and saying, “We’re hoping this will go to board,” Kaiser says, to having some original board books become so popular they’re subsequently reissued as picture books.—GC |

Gail Cornwall works as a mother and freelance writer in San Francisco.

RELATED

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

The job outlook in 2030: Librarians will be in demand

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing

A storied history

A storied history

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!